Paulina Olowska is an excavator of the past. The Polish artist scours histories looking for hidden clues and meanings that we may have missed during the lived moment itself.

She’s painted idyllic utopias of the post-war era, and in one series, titled “Applied Fantastic,” she painted a set of postcards from the 1980s that featured women posing in patterned sweaters—a relic of life in the Cold War era.

Paulina Olowska (2017). Photograph by Thomas Manneke.

In her most recent exhibition, “30 Minutes Before Midnight,” at Simon Lee in Hong Kong, she has turned her gaze—a decidedly feminine one—on old movies and the women who sometimes tragically, but often magically, filled the screens.

The exhibition title is a reference to Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil by John Berendt, which was later adapted into a movie and is filled with references to voodoo, mystery, and murder—all themes that run throughout Olowska’s works.

Recently, we caught up with Olowska to talk more about the myriad influences at play in her work.

Paulina Olowska, Grazyna, The Modernist (2021). Courtesy of Simon Lee.

In these works, the viewers watch women, who in turn watch us. How do you see the female gaze functioning in your works?

I am the female gaze. I plant it, care for it, flourish it, sprinkle it (with a watering can) every morning, and, just before midnight, I wish it goodnight. Try to see it yourself. Here, put on this pair of binoculars, see? The female gaze is south, west, north, east.

It is like a pumping machine, a very heavy, high-speed locomotion (you can hear the heavy machinery sounds … tudum tudum tudum phhhh phhh, phhh dumm). When you try to pick it, and even if you manage to get a hold of it and hide it in your pocket, it does not disappear because of the long mycelium growing beneath, right to the center of the earth.

How did the novel Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil—and the film adaptation—influence you and this body of work?

I adore Minerva the witch in the film. There is a scene where she stands with Jim Williams, played by Kevin Spacey, in the nightmarish graveyard, and in her usual grotesque manner she pronounces: “The half-hour before midnight is for doin’ good. The half-hour after midnight is for doin’ evil—seems like we need a little of both tonight.”

Savannah is a special place. Last winter I visited while I was working on the show “Mainly for Women” at the SCAD Museum of Art. I was fortunate to stay at Magnolia Hall, a historical house overlooking Forsyth Park, where the trees are covered by Spanish moss that hangs dramatically from its limbs. The film, like Savannah, features characters who are twisted in time, as though time had been sped up, going backward and sometimes sideways. Hallucination happens naturally, all is beautiful and surreal.

Paulina Olowska, Vali, The Witch of Positano (2021). Courtesy of Simon Lee.

These paintings all make references to films in one way or another. The paintings include imagery of cult figure Vali Myers and the film about her life, The Witch of Positano (1965), Samantha Robinson in The Love Witch (2016), and Valerie Leon in Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971). What drew you to these movies? What do actor and character come to mean in these images?

My mother was a visionary, a medium. She taught me some techniques about how to foresee and how to “get deep with the subject matter,” which I do through painting and collage. Painting is a form of meditation and a means to connect with unique characters, dead or alive. I created such a mediation with Lucy McKenzie, Alina Szapocznikow, Zofia Stryjenska, Deborah Tuberville, and now Vali Myers. I would like to reach out to Queen Tera, who is featured in Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb. Hopefully, I will do this on my next expedition to Egypt.

Installation view of “Paulina Olowska: 30 Minutes Before Midnight” (2021). Courtesy of Simon Lee.

I’ve read that the tensions between night and day play a role in these paintings. Can you explain that to me?

The layout of the show was prepared according to the colors of the day and night, installed from light to dark in a clockwise direction. The colors begin bright and pastel-like, the colors of early morning. Mid-day is represented by the temperature in Grazyna, The Modernist (2021), depicting 1970s actress Grażyna Szapołowska playing with her German Shepherd in a spring garden full of green foliage with only the concrete from a social modernist building peeking through, and in Maidens Fishing for Bohemian Merelf (2021), which shows two Bavarian maidens playing with a stick as they encounter a water monster. Afterward, the colors go beyond the palette, so black and white with a touch of color from behind. The subject matter shifts according to the darkness of the image surrounded by symbols, visions, and stars.

There is duality in each painting. We think we see serenity and beauty, but actually each painting presents and carries an internal drama, or a true story. For example, Night Discontent, Day Drama (2021) appears light and uplifting, but really it shows two underaged females waiting for their night shift as sex workers. A friend of mine, Diana d’Arenberg, described them as “Thanatos meets Eros” which I quite like.

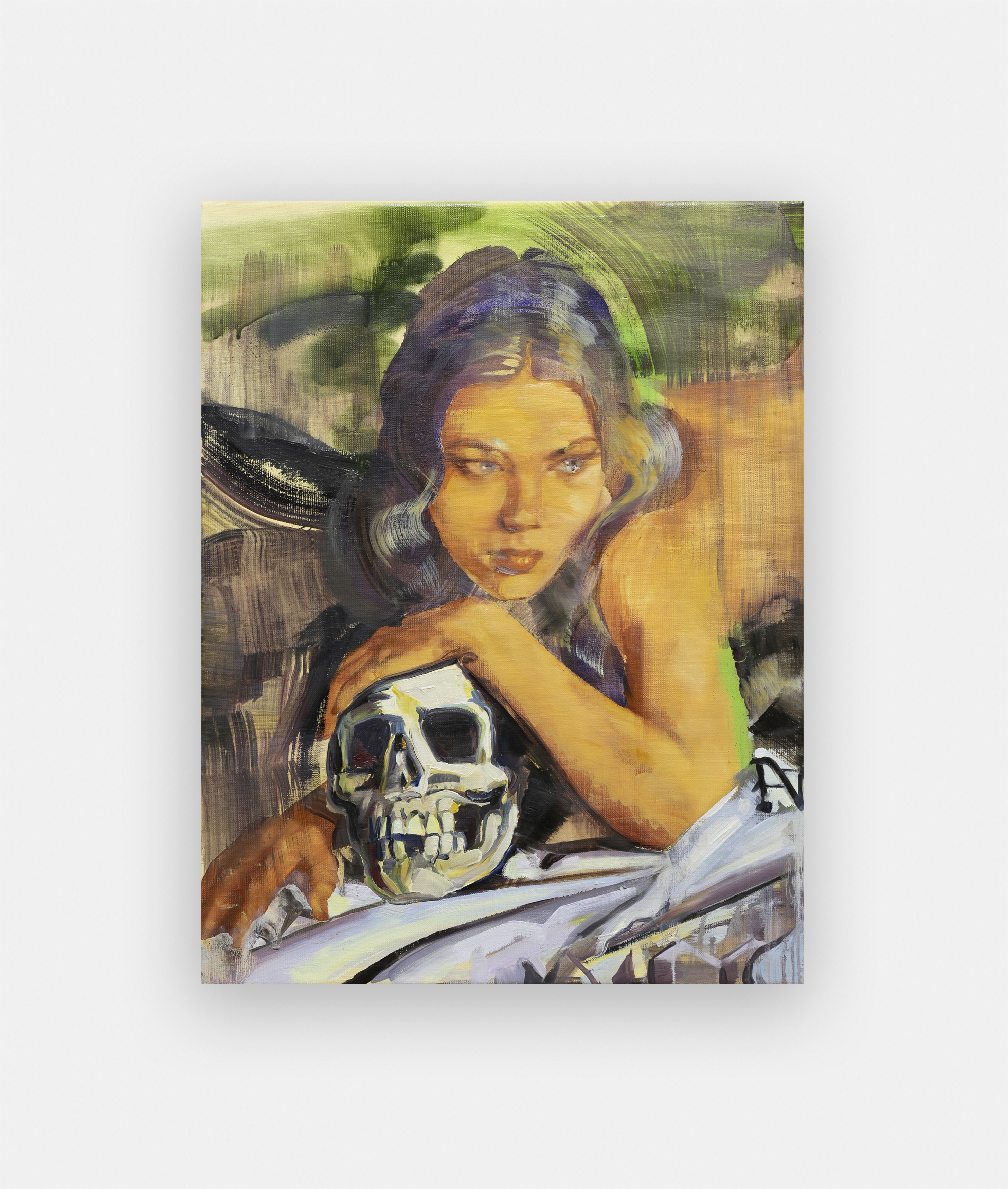

Paulina Olowska, Tera, The Queen (2021). Courtesy of Simon Lee.

If you had to choose a figure from myth literature or film that you most identify with, who would it be?

Lilith, the queen of Night. Lilith represents freedom of sexuality. According to mythology, she was the first wife of Adam, who had an affair with archangel Samael and was damned to spend the rest of her years in darkness. She returns only in dreams. To some, she might appear as a demon but to contemporary women, she stands for the liberation of our sexuality.

If you could own any artwork in the world, what would it be and why?

Owning is a strange concept. I prefer to fall in love with the object. My first real “chill” was seeing a painting by Marie Laurencin in person. Recently I rediscovered the wonderful Warsaw-born surrealist Maria Anto. I highly recommend Florentine Stettheimer as one of the top visual pleasures, and the paintings of Sylvia Sleigh are so wicked.