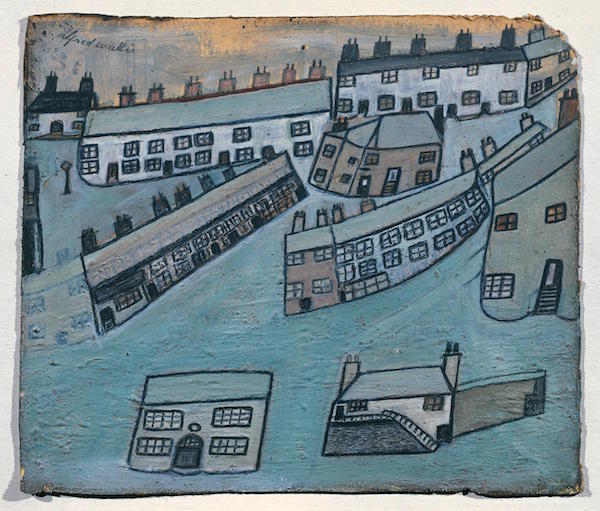

Photo via: Tate

Millions of artworks and historically important documents that have remained hidden from public view for centuries because their copyright holders could not be identified, are being made available to the public today in the UK, the Independent reports.

The release follows the introduction of a new copyright regulation that allows the reproduction of “orphan artworks” on websites, in books, and in other media. The regulation stipulates that if any right owners came forward subsequently, they would still be entitled to ask for future remuneration.

The UK-based scheme coincides with the implementation of a similar policy in the EU: the Orphan Works Directive, which enables cultural institutions to digitize items of these characteristics and display them on their websites.

This new regulation is hugely important in the UK, where up to 50 percent of archival records are considered “orphan works.” Naomi Korn, chair of the Libraries and Archives Copyright Alliance, told the Independent: “The delay to much needed Government reforms of copyright laws limits and distorts the telling and understanding of our nation’s history.”

The institutions that will benefit from this law include Tate, the Museum of Childhood, the Imperial War Museum, and the Royal Air Force Museum.

Tate, for example, will now be able to reproduce the 12 Alfred Wallis paintings it owns. When Wallis died in 1942, he did not have any surviving family, so the paintings became “orphan works.” Even though the copyright of these works expired in 2012, 70 years after the painter’s death, they had entered a legal gray area that prevented them from being reproduced and disseminated to a wide audience.

The Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Another interesting case is that of the Bethlem Museum of the Mind, which holds a large collection of artworks created by workers and patients of the Bethlem psychiatric hospital, amassed since its creation in 1247. These works—of huge value in the historical understanding of art therapy—were often crafted by anonymous artists, or patients hiding under a pseudonym, so they were also “orphan works” that couldn’t be shared until now.

Baroness Neville Rolfe, Minister of Intellectual Property, told the Independent: “The scheme has been designed to protect right holders and give them proper return if they reappear, while ensuring that citizens and consumers will be able to access more of our country’s great creations, more easily.”