If you’ve seen one skull, you’ve seen them all, right? They look more or less same and its hard to imagine they once inhabited living, breathing faces. A new display opening in March at Perth Museum in Scotland brings back to life four ancient faces that have been digitally reconstructed from human remains that were excavated in the local area.

An interactive experience will allow visitors to follow along with the reconstruction process, courtesy of craniofacial anthropologist Dr Christopher Rynn, who more often works on forensic cases. As audiences meet their ancestors, they will learn how each skull provided a unique record of that person. Subtle aspects of its structure reveal a surprising depth of detail, such as whether the owner had ears that stick out or a particularly pointy nose.

“You’re trying to make the face look like a real person,” explained Rynn. “You want museum visitors to feel like they’ve met someone not come in and say, what’s wrong with it, it looks like Shrek.”

The portrait process starts with the bone, adding eyes, cartilage, muscle, fat, skin, and, finally, the finishing touches that make any face recognizable: hair, eye color, and skin tone. The final portraits are animated by A.I. so that they can blink and move their heads—a touch of artistic license that isn’t allowed in forensics.

Striking the right balance between real and too real was top of mind for Rynn. “The more real you make a face, it can start making people feel uncomfortable. Trying to get out of uncanny valley to the other side is a Sisyphean task,” he said.

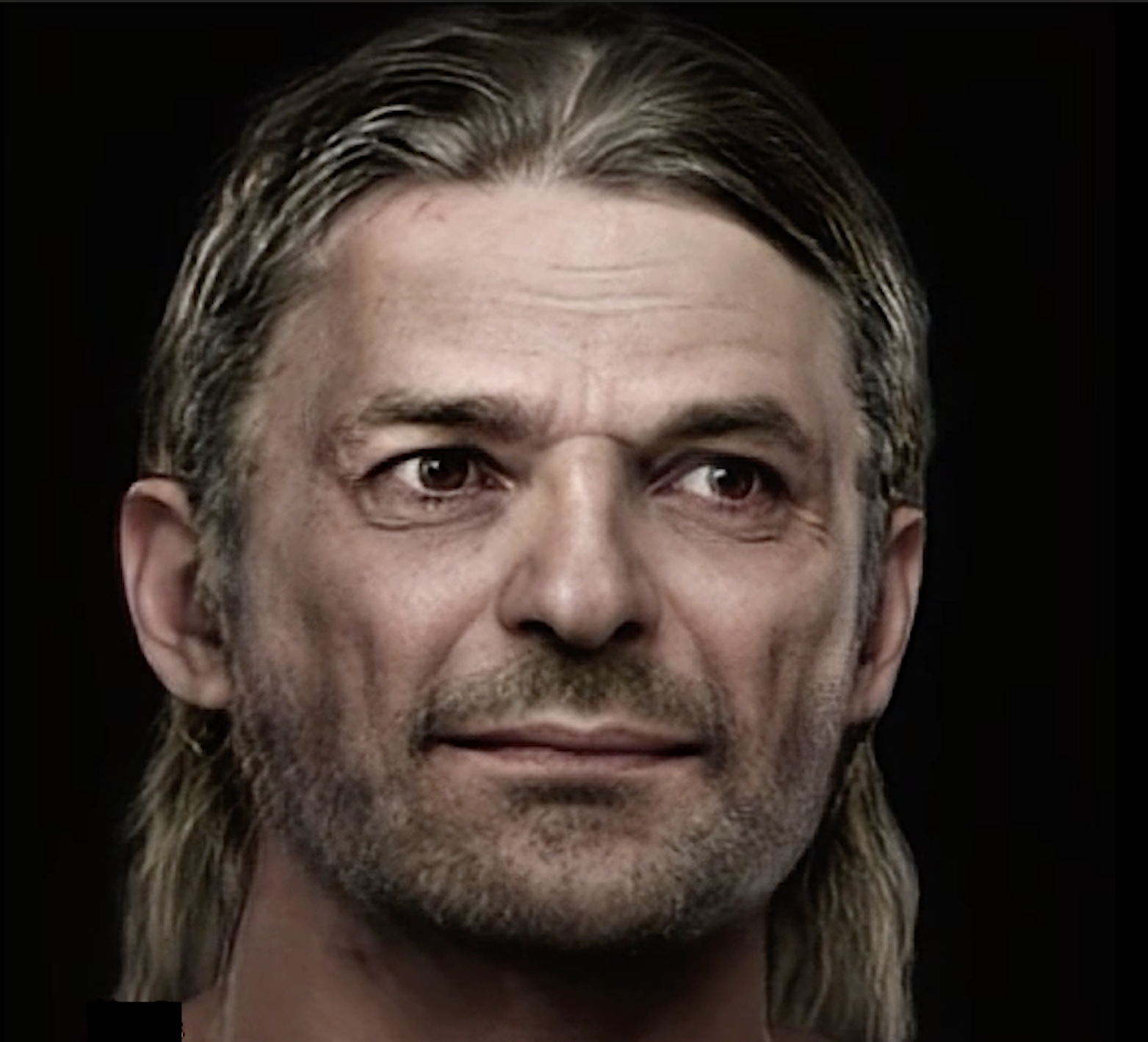

Digital facial reconstruction based on remains of a Late Medieval male, who lived in the 13th or 14th century, found at Horsecross in Perth. Copyright Perth Museum.

One of the recovered faces is that of a young Medieval man aged between 18 and 25 whose remains were found in the early 2000s at the very site where Perth Museum now stands. Though radiocarbon dating would suggest the man was buried in the 13th century, he was found with two silver coins whose dates indicate instead that he was buried in the late 14th century.

The bones tell us that this man’s growth was disrupted several times during childhood, perhaps due to illness or malnutrition. His fractured ribs suggest he sustained blunt force trauma to the chest and his body was crammed into a small, shallow pit pointing to a hasty burial that reinforces the theory that he may have been murdered.

Naturally occurring marks on bones can provide important details of a person’s life as well. For instance, the contours of a skull can tell us more than simply whether a person had a large forehead or an underbite, according to Rynn. Though you can’t tell the exact ear shape, the measurements of a bony protrusion behind the ears known as the mastoid process reveals whether their ears were big or small, had lobes, or stuck out.

As for noses, their shape tends to be the mirror image of the nasal aperture. The so-called nasal spine, a tiny protrusion shaped like the thorn of a rose, tells us if the nose was upturned or downturned and, if the spine is split, the cartilage diverges to create a bifid or “cleft” nose.

“Some parts of the face are an echo of the skull, and other parts of the face are a mirror,” explained Rynn. “Its an anatomical pattern.”

Another skull that Rynn reconstructed was that of a Bronze Age woman aged around 40 whose burial chamber was discovered at Lochlands Farm in 1962. She was about five feet tall and her spine showed signs of osteoarthritis and possible chronic back pain. More surprisingly, the lower left-hand side of her skull is missing, which may be evidence of an injury that ultimately caused her death.

Digital facial reconstruction based on remains of a Bronze Age female, who lived c. 2200-2000 B.C.E., found at Lochlands farm, Perthshire. Copyright Perth Museum.

Digitally restoring the missing part of her face was easy enough: Rynn simply copied and flipped the surviving side. He created versions of her face with different hair and eye colors according to what we know about people from the region in that period. He even experimented with the expressions that might settle into the face more permanently after years of living with chronic pain.

Rynn is very excited about the project going public but not without some trepidation.

“In Scotland, people can tell what clan you have ancestry from,” he said. “People have roots that run really deep, so local visitors to the museum will know if the reconstructions are wrong.”

“If they don’t like these faces, they’ll tell me,” he adds, noting that facial reconstructions have a curious capacity to invoke strong emotional responses in people. In 2017, he reincarnated Lilias Adie, an elderly Scottish woman who was accused of witchcraft in the early 16th century.

“I just depicted a nice old lady who was murdered, because that’s what actually happened. There’s no such thing as a witch,” said Rynn. “People emailed me saying you made her look too nice. She would have been ugly or no one would have reported her as being a witch.”

He also notes that people often struggle to grasp how familiar people from the distant past might appear to us now. “Ancient Egyptians had scissors 4,000 years ago,” he said. “Why do people think if you go back 100 years, everyone was a caveman? They had better teeth than I do!”

“Stories for Faces” also features a Pictish agricultural laborer from the Iron Age and a 16th century Medieval nun. The permanent display will be made public when the Perth Museum reopens on March 30th, 2024.