Photo courtesy the artist.

Internationally known for his sculptural evocations of a post-apocalyptic, post-human world, Argentine artist Adrián Villar Rojas won the fifth edition of the Prix Canson at Paris’s Palais de Tokyo on Monday evening.

The prize includes 10,000 Euros’ worth of Canson paper; an exhibition; a display at an art fair; and the purchase by Canson of at least one work.

Villar Rojas, 35, beat out artists Trisha Donnelly (New York and San Francisco), Rokni Haerizadeh (Dubai); David Musgrave (London); and Mithu Sen (New Delhi). The five finalists were whittled down from 41 nominees put forward by the jurors and Canson representatives; their work is on display in a sunny top-floor gallery at the Palais de Tokyo through July 1.

Villar Rojas wasn’t present at Monday evening’s award ceremony or that morning’s presentation by artists to the jury, as he was busy preparing for the upcoming Istanbul Biennial.

The artist has become a fixture on the international exhibition circuit; he’s also included in the current Sharjah Biennial, and has appeared in Documenta 13 (2012) and the 54th Venice Biennale (2011), where he represented Argentina. Last year, his work adorned New York’s High Line.

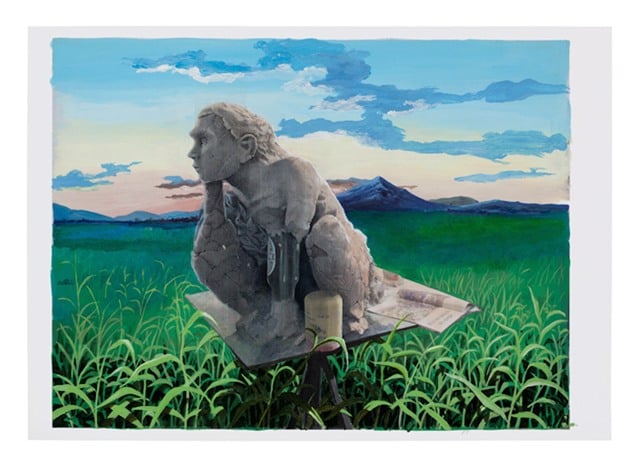

Adrián Villar Rojas, from the series “Return the World,” 2013, inkjet print, watercolor and pencil on paper.

Photo courtesy the artist.

His giant sculptures are often made to be destroyed or are allowed to crumble over time. They evoke the aftermath of disasters, or are meant to suggest what traces humankind might leave behind after its demise. One of his massive sculptures, Where the Slaves Live, happens to be on view at Paris’s new Fondation Louis Vuitton.

Villar Rojas’ works on paper, executed in inkjet print, watercolor, acrylic and pencil, present views of what appears to be his cavernous studio, with figurative clay sculptures in progress. One small drawing depicts what looks like a stone outcropping outfitted with cracked bandshells hundreds of feet above the ground, as if documenting the abandoned setting for some futuristic music festival.

The other nominees form a roster of similarly market-approved and institutionally recognized figures, if not quite as visible on the global scene than Villar Rojas. Donnelly’s résumé includes exhibitions at London’s Serpentine Gallery and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Haerizadeh was included in the recent New Museum exhibition “Here and Elsewhere.” Musgrave is represented by New York’s Luhring Augustine Gallery; Sen had a solo exhibition at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum in Michigan in 2014.

Donnelly, who works in a broad range of formats, is represented in the Canson exhibition by a handful of unframed drawings pinned to the wall; some bear only the most minimal of markings, one in particular appearing to have been abandoned after just a few slashes. Even the more elaborated ones offer little for the viewer to grasp hold of; one sheet suggests a sketch of part of the skeleton of some unknown animal.

Haerizadeh’s drawings form the basis of short, silent animated videos, two of which are on view and are made using up to 6,000 individual sheets, based on found imagery from sources like YouTube. The artist fled the conservatism of his native Iran for what he hoped was the relative permissiveness of Dubai; his 2014 video Letter! shows topless women protesting against radical Islam outside a German mosque, with slogans like “Allah created me free” and “Woman Spring is coming” painted on their bodies.

Haerizadeh submits his figures to humbling transformations, often giving them animal heads to suggest human savagery. “Growing up in Tehran during the Iran-Iraq War had a great impact on my generation,” the artist has said. “Thinking about life and death, as a child, makes you very serious.”

Musgrave’s engrossing drawings appear to be full-size representations of sheets of paper that have been submitted to various manipulations, like scratching, ripping, and folding. They’re actually not based on existing objects, he told me, and so, in a pleasing twist, seem to constitute representations without an original.

Though Sen’s work encompasses formats like sound, performance, and installation, she’s deeply involved with paper, having developed her own for some of her works. “My work is very sexual, very erotic,” she told the jury at a presentation by the artists on Monday morning. “I work with subjects like homosexuality and nudity, but for me they are not taboos.”

Three visually lush works displayed in light boxes use multi-layered paper to depict fancifully transformed human figures in mysterious interactions. A naked man holds a fish in place of his penis, and his head is replaced with a vivid bouquet of red roses. Elsewhere, a crouching, nude woman whose head has dissolved into wisps of smoke administers to a man’s genitals while a bird appears to peck at her anus.

Founded in 1557, the Canson paper company, located in the French town of Annonay, boasts having designed paper for artists such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Aristide Maillol. Artists such as Eugène Delacroix, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Andy Warhol have also used its products.

The past winners of the Prix Canson are Simon Evans (2014), whose Prix Canson show will take place at the Palais de Tokyo in 2016; Virginia Chihota (2013); Ronald Cornelissen (2011); and Fabien Mérelle (2010). Mérelle has said that especially in view of his proclivity to small format drawings, the prize will provide him with paper to last him for probably 20 years.

This year’s jury consisted of Swiss-born collector and Cahier d’Arts owner Staffan Ahrenberg; New Museum curator Natalie Bell (New York); Drawing Center curator Claire Gilman (New York); art historian and former director of London’s Whitechapel Art Gallery Catherine Lampert; MoMA PS1 curator Mia Locks; Palais de Tokyo (Paris) president Jean de Loisy; Christine Macel, head curator in the department of contemporary and prospective creation at Paris’s Centre Pompidou; and Bala Starr, director of Singapore’s Institute of Contemporary Arts. The Brazilian artist Tunga served as president.

After Monday morning’s presentation by the artists, which I observed in part, the jury shared lunch at the museum’s restaurant, where they reported a lively debate.

“These things are the most fun when people really have to make a case,” Locks told me that evening, “when they have to argue for their choices.”

“Some jurors thought about how the artists are advancing the use of paper,” Gilman told me, “while others simply argued for the artists they think are the most ambitious and successful.” The choice didn’t have to be unanimous in the end, she said, the winner being determined instead by calculating numerical scores the jury members assigned to the artists.

Next year they’ll tally the numbers in New York; the 2016 Prix Canson will be awarded at the Drawing Center.