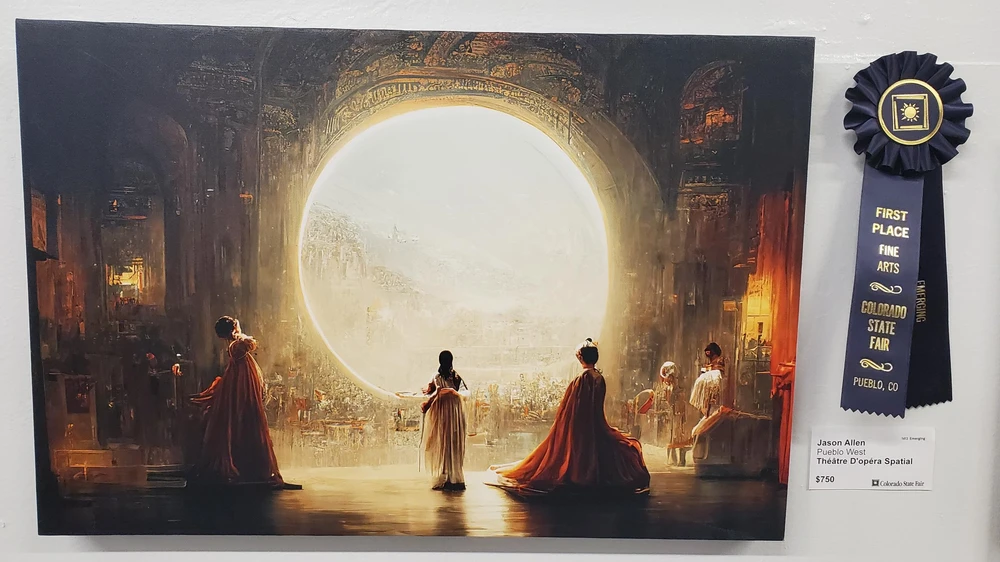

Earlier this month, the U.S. Copyright Office (USCO) deemed that an A.I.-generated artwork, which won the top prize at the Colorado State Fair last year, was not eligible for copyright protection.

In its decision, the office ruled that Théâtre d’Opéra Spatial, created by artist Jason Allen, “lacks human authorship” and falls outside the purview of copyright law, which “excludes works produced by non-humans.” Allen, however, has emphasized his hand in the work: using Midjourney, he said, he “entered a series of prompts, adjusted the scene, selected portions to focus on, and dictated the tone of the image.”

This is but the latest blow to A.I. artists seeking copyright protection for their creations.

In February, the USCO granted then withdrew protection for Zarya of the Dawn, a comic book created by Kristina Kashtanova using Midjourney. Computer scientist Stephen Thaler has likewise seen his many copyright claims for his A.I.-generated artwork shot down in the U.S. and other countries.

Stephen Thaler has unsuccessfully sought copyright protection for the A.I.-created A Recent Entrance to Paradise. Photo via U.S. Copyright Office.

That artists might not receive protections for their A.I. works could have serious implications for the growing field of digital art, Thaler told Artnet News in January.

“Sadly, the result will be orphaned art, as well as inventions, and other forms of intellectual property that will all be denied legal protection,” he said. “As this crisis grows, an increasing number of artists and inventors will be fraudulently taking credit for the efforts of creative A.I., and in that process, creating chaos.”

While the USCO has historically only considered works with human authorship copyrightable, it issued a new rule in March that allows the copyrighting of A.I.-generated work if a human can prove they put a “meaningful” amount of creative effort into the final content.

“This sounds reasonable to me and I broadly would agree with USCO,” Katarina Feder of the Artists Rights Society told Artnet News. “A generated work should be eligible if there was significant human intervention in its creation.”

“I think the next few years will give us a better idea of what counts as a ‘meaningful amount’ of human ‘creative effort,’” Samantha Moore, the in-house counsel for the Artists Rights Society, added.

At the international level, the Berne Convention or the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works stipulates that “protection shall operate for the benefit of the author” but doesn’t define “author,” Audrey Kim, artist and director of the A.I.-themed pop-up show Misalignment Museum in San Francisco, pointed out.

She added that, under European Union copyright law, there is no definition of “author,” but that case law has established that only human creations are protected.

Audrey Kim in front of Genesis: In The Beginning Was The Word by Eurypheus at the Misalignment Museum, 2023. Photo: Amy Osborne/AFP via Getty Images.

“When it comes to A.I., at the heart of many of these discussions is what it means to be human,” said Tina Tallon, a musician and expert on the use of artificial intelligence in music. “We have to figure out what constitutes human authorship. We also have to define what ‘A.I.’ means and the extent to which A.I. tools, and how much or often, can be used before the significance of the human’s contribution is degraded.”

She added that there are many artists and creators who use A.I. on a daily basis. At what point does an artist’s use of neural networks and other A.I. technologies make it so that the artist can’t claim copyright of a piece?

“Spellcheck is an application of A.I., for instance—will that have to be disclosed? How many words can be misspelled and corrected by spellcheck before the human did not actually write the piece?” she said.

Tallon said most panelists in hearings before the USCO are not artists, which she called “extremely concerning.” She added: “Sadly, artists often represent the smallest group of people invited to the table when these conversations are happening and these structures are being built.”

As an artist, Kim conducted a project in which she trained an OpenAI neural network on the opus of composer Phillip Glass, which activated a complex web of copyrights.

“Before we could begin training the neural net to discover patterns in Philip Glass’s music, we needed to gain approval from Glass’s publishing company for official use of his MIDIs as training data,” Kim said. “This raised questions of how rights for the trained models, and the musical outputs of those models trained on Philip Glass’s copyrighted music would be partitioned.”

Kim said the team established that the rights for the neural net would be kept with OpenAI, but the models trained on the copyrighted music would be used only in connection with the project and be destroyed after it ended. The rights to the compositions that came out of the project were also claimed by the publishing company that oversees Glass’s music.

“I was worried about the implications of arranging rights in these ways and if it could set a precedent disadvantageous for creative innovation and artists,” Kim said.

“The theoretical layers about what could be a domain of copyright and ways in which rights could be partitioned was dizzying. What is the line between mimicking and inspiration? Can a ‘personality’ be copyrighted?”