At Celine’s men’s winter 2023 show at the epochal Paris nightlife den Le Palace, a very Hedi Slimane army of rockers stormed the runway—almost all in wraparound John Cale-era Velvet Underground sunglasses. The creative director, who spent many late nights at the fabled club in his youth, sent out a lot of leather, from silver-fringed blazers to oversized 1980s-style Breakin’ jackets (one adorned with leopard-print appliques). Slimane’s requisite classic moto was also remixed and remade in different iterations—cherry red with gold epaulets, gleaming silver, and a few so exorbitantly studded they’d set off a metal detector.

There was a leather outerwear corollary for every music subculture (the post-punk trench was particularly killer). Genres were referenced and collided, and the boundary between brand-new and relic blurred. The same could be said for the pulsing, thumping soundtrack—a hard-to-quantify, sexually charged dance-rock hybrid that was shockingly released in 1977. The lyrics, “oh, girl, I touch myself,” is heard underneath electronic layers, coupled with the yelping male version of climax a la Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love.”

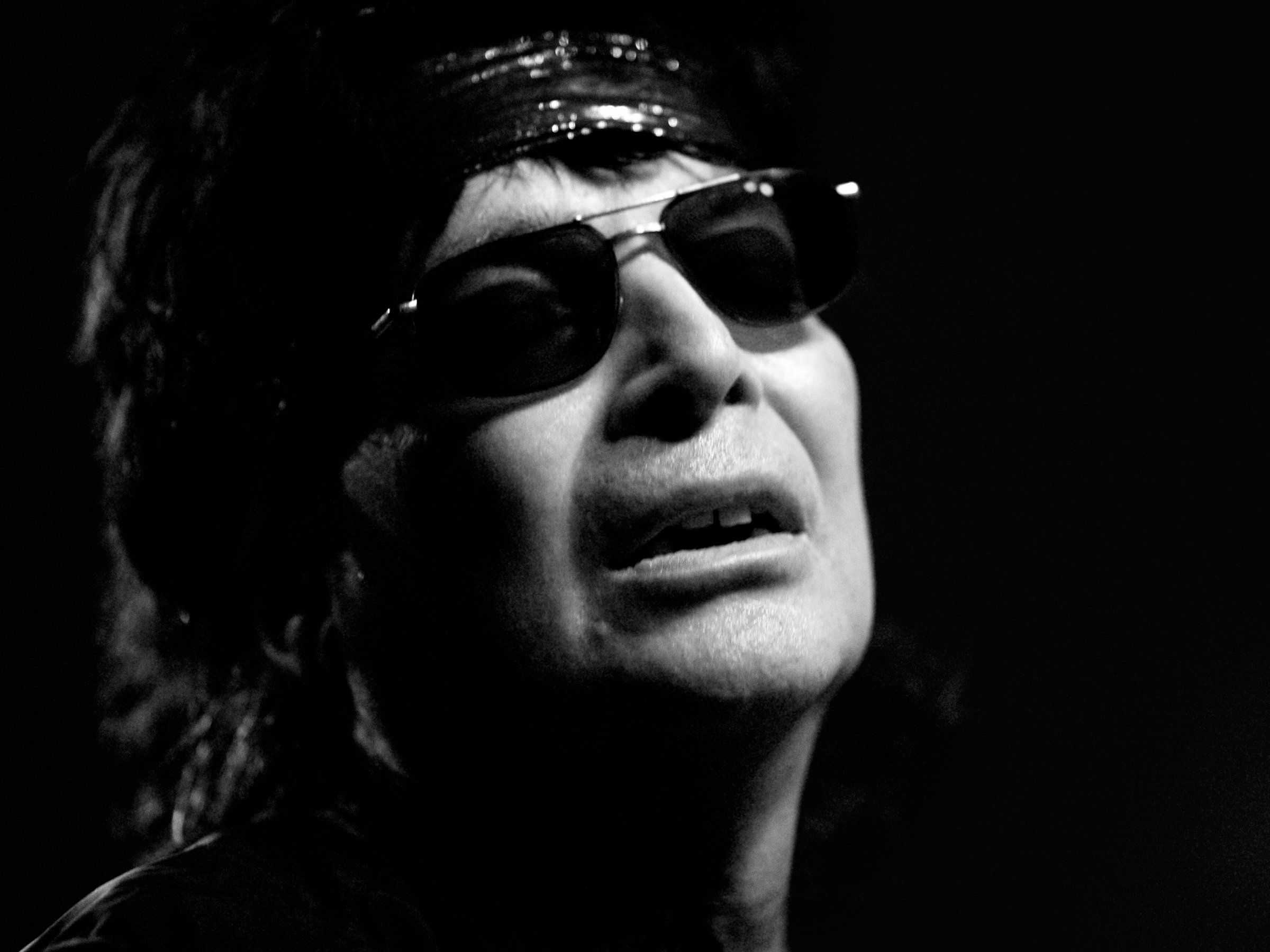

Left: Alan Vega in 1978. Photo: Bob Gruen. Right: A model wears a tank based on Vega’s “ransom note” art in a Celine campaign image shot by Hedi Slimane. Courtesy of Celine.

The singer is Alan Vega, who died in 2016 at 78. “Girl” is from the self-titled debut album of his band Suicide, an influential eons ahead-of-their-time duo. This version of the track was subtly updated especially for Celine’s runway. The Celine collection had elements of electro, punk, rockabilly, doo wop, Teddy Boy—you name it, and it was in there. This was also Vega’s modus operandi, more pastiche than rip-it-up-and-start-again (this 1983 performance is a great intro for the uninitiated to Vega’s extensive solo career).

Was Slimane influenced by Vega’s outsized stage persona? Also hidden beneath all Celine’s glammed-out cowhide and nightclub hauteur was a capsule collection based on Vega’s series of cut-and-paste ransom letter-like artworks. Although Vega’s underground fame is primarily for his decades-long music career, he had an extensive art practice. The second Celine x Alan Vega drop was released earlier this month and includes a hoodie, sleeveless tee, and a cardigan.

Vega’s wife, Liz Lamere, and son were in the front row. “It was amazing,” Lamere said. “Alan would have appreciated that it was coming from an authentic place with Hedi. It connected to something that was intrinsically important to his growth as a creative—Le Palace and that whole rock vibe. We were just beaming. I felt like Alan was there. His voice transformed the space.”

But Vega was the personification of anti-establishment. What would he think of his fashion foray? “When people asked him to collaborate, it was never about, ‘oh, what’s in it for me?’” Lamere explained. “Or ‘how would that reflect on my being seen [by] the outside world?’ He would love the fact that Hedi was interested in using his collages because he held him in such high regard. It was always about the creative process.”

Alan Vega’s untitled drawings from 1978 and 1993. Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

The Celine project is the preamble to what’s going to be a very Vega 2024. A biography, Infinite Dreams: The Life of Alan Vega, co-written by Lamere, is scheduled for a June release. It will be preceded by the brutally haunting album Insurrection. The collection of lost recordings, which features industrial-chic bops mixed with experiments that make for extremely uneasy listening, will be released in the first half of the year. It’s produced by Lamere and Jared Artaud, of Suicide torch-carriers The Vacant Lots.

“Sometimes it feels like Alan was guiding the process,” Artaud says of compiling the album. “He’d go into the studio for weeks just to create sounds. We are left with what we call the Vega Vault of sounds, of finished and unfinished songs. Alan working in the studio, working on a drum machine, and then just saying, ‘fuck it,’ and switching over and doing something else. Alan would just go in and create. So there’s a tremendous amount of material.” This will be the second posthumous Vega album (Mutator was released in 2021).

Alan Vega, Untitled (1971) Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

Lamere was her husband’s creative collaborator throughout their marriage, recording and performing with him. “To add a little more color as to why there is so much material,” she explained. “It’s how Alan approached creating. He went into the studio with the intention of just creating sound—not so much I have these songs to record and then release albums. He might have recorded sounds from the street on his little handheld recorder and then run that through effects machines and just layer sounds. He was creating a sound library. And then he would start layering them to create songs, then add vocals. Every so often, I’d say, ‘we need stop whatever cluster of songs we’re working on now.’ And then Alan would focus on finishing a conceptual whole, which would become an album.”

An undated photo of Alan Vega with Light Sculptures. Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

If this process sounds like a hot mess, well, that’s the beauty of it. “One of Alan’s philosophies was that there are no mistakes,” Lamere said. “Wherever we are right here in this moment in time is where we’re meant to be and really literally work with whatever is evolving. He would say, ‘when you’re creating something, you might make a conscious decision, or you might have a conceptual idea.’ But then the piece, whether it’s music, art, whatever it is, starts kind of dictating what it’s becoming. And you have to be very free to flow into that. That was extremely freeing to me.”

When they met in the early ’80s, Lamere was a drummer in a punk band, but she was also a corporate lawyer. “I was in an environment where you had to be extremely precise and detail oriented,” Lamere said. “Being able to switch gears to be completely free in the creative process as Alan was amazing.”

Vega’s art career began at Brooklyn College in the 1960s. “He studied under Kurt Seligmann, the surrealist Swiss American painter, but I think most importantly, Ad Reinhardt, the minimalist. He was trying to break everything down to its most essential parts,” Lamere added. “Alan would say to me, ‘the hardest thing to do is something super minimal because each element needs to be able to stand on its own.’ He was always looking for those essential elements—and then layering them. He did it in art. He did it in music. Again, whatever the medium was, he would use whatever materials were at hand.”

Alan Vega’s Untitled 1972 sculptures at OK Gallery. Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

Pre-Suicide, Vega showed his light sculptures, conglomerations of debris, found detritus, and organized chaos at OK Harris Gallery in the early 1970s and then segued into focusing on music. A Vega solo show inaugurated Barbara Gladstone’s move from midtown to SoHo in 1983. All the while, he never stopped drawing and creating work. His next art renaissance occurred in 2002 with a Deitch Projects solo show. “Jeffrey Deitch said he was probably the most non-careerist visual artists he had ever encountered,” Lamere recalled. “It truly and purely was about being in the moment and creating.” Vega also had a solo show at Invisible Exports in 2015. There is a stockpile of work, and Lamere hints at a larger art project on the horizon but won’t give details yet.

“Alan said, ‘you know, Suicide really should have been named Life,’” Lamere said. “It was really about life. There’s that duality of beauty and joy and transcendence that you find in ‘Dream Baby Dream’ or ‘Girl.’ And then there’s the despair and heartache and the harsh realities of life in ‘Frankie Teardrop.’ The overarching theme is always one of hope. People misunderstood, if they thought it was doom and gloom.”