Alex Harsley’s new exhibition, a survey of his more than six-decade photography career at Brooklyn’s Pioneer Works, is a big deal. In terms of scope, it’s likely the biggest of his life. And yet, the octogenarian artist isn’t exactly taking a victory lap.

“I’ve moved far beyond that stuff,” he says, referring to the retrospective nature of the show, which includes New York street photos, arty portraits, and experiments in video from the 1950s through to today. “I’m into a whole different area [in terms of] exhibiting now.”

We‘re sitting inside the 4th Street Photo Gallery, a cramped storefront space in the East Village overstuffed with old cameras, darkroom gear, and prints—thousands of prints, all lining the walls and stacked in piles of indeterminate age (they might be load-bearing at this point). Harsley has occupied the space for 48 years.

“This,” he says, gesturing to the space around him, “this is like an installation.”

Indeed, 4th Street is like a living, breathing artwork. What has historically been an exhibition space for up-and-coming photographers is, today, more like Harsley’s personal office or studio. At almost all waking hours of the day you can find him in there working—scanning slides, editing photos, hanging and rehanging his work. At 83, his days of roaming the streets of New York with a camera in hand are mostly over, but he has scores of archives still to work through.

“Alex is really unsentimental about his own work,” said Vivian Chui, Pioneer Works’s director of exhibitions who co-curated the show with Harsley’s daughter, Kendra Krueger. “He really just wants to make images. He’s not thinking about his legacy, he’s not thinking about where his work was. He’s always much more focused on where his work is going.”

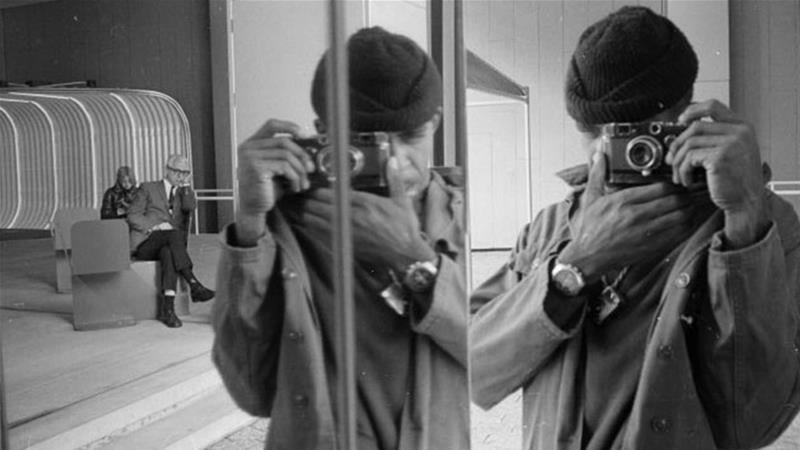

Alex Harsley, Nite Meetings. Courtesy of the artist.

Harsley was born outside of Rock Hill, South Carolina, in 1938, and grew up on a rural cotton farm. Only one or twice a month did he see a car or electricity, he recalled. That is, until age 10, when he moved with his mother to New York.

Following a stint in the army in his late teens, Harsley moved back to the city, bought his first camera, and learned his way around the darkroom while working as a staff photographer at the district attorney’s office. Then the young photographer was off: churning out 35mm pictures of New York’s faces and places; capturing activists, athletes, and musicians in action.

In 1971—half a century ago this year—Harsley founded Minority Photographers Inc., an artist-run non-profit based in his apartment that showed the work of up-and-coming image-makers. Two years later came the group’s headquarters: a derelict street-level space offered by the city on the cheap, thanks to Minority Photographers’ 501c3 status. That was the birth of 4th Street Photo. It’s the same space Harsely’s sitting in today.

Alex Harsley, Playing In Chinatown (1970). Courtesy of the artist.

So out of place in the now hyper-gentrified neighborhood is 4th Street that it’s easy to walk past the spot and not even see it, the way you would a travel agency or a phone booth or other neighborhood vestige. And yet, Harsley still gets his fair share of walk-ins coming to look at his work; many even buy it. During our interview, a mother dressed in athleisure came in to pick up a couple of prints for her college-age daughter, who had just moved to the neighborhood. I asked if they’d seen the show at Pioneer Works. They said they had no idea how to get to Brooklyn.

For Harsley, an artist largely ignored by museums and galleries in his career, passersby looking to purchase a piece of New York history are his clients. And he’s okay with that. “It’s not about me and my name,” he said. “It’s about the content. So I like to stay behind the [work].”

But that’s not to say the photographer doesn’t have fans in the art world. If off-the-street visitors are one-half of Harsley’s collector base, then the other half is fellow artists, many of whom were affiliated at some point with 4th Street Photo or Minority Photographers.

Alex Harsley, Cousins (1980). Courtesy of the artist.

For generations of up-and-coming photographers in the 1970s through the turn of the century, 4th Street was a site of community, mentorship, and—perhaps most importantly—wall space. Among those who have shown in the gallery are Dawoud Bey, David Hammons, Eli Reed, and Andres Serrano, while others known to have frequented the space include Robert Frank, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Cynthia MacAdams.

Harsley, for his part, has stories about all of them—and he’d surely be happy to share them should you stop by. (Bey was a “serious hustler,” he said with admiration; Frank “sold his soul to the devil.”) But listen in and you may detect a latent tinge of bitterness, too. It’s the chip on the shoulder speaking: success never came to Harsley the way it did those heavyweights, even though he considered himself a mentor to many of them.

“When I started Minority Photographers, I had to leave myself behind. I worked very hard at helping other people become successful,” he said. “But in the course of all of that I had to sacrifice my own interests.”

The mood hung heavy for a second, before Harsley lit it up with a joke: “If I had known I was going to be in the same place [50 years later], I would’ve said, ‘Let’s do something else!’”

Alex Harsley, Fashion Shoot (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

“I don’t know if I believe that,” Chui said when I recalled this comment to her. It’s not that Harsley forfeited a great legacy in the name of 4th Street and Minority Photographers; those projects are his legacy. “The nonprofit and the gallery were so special,” she said, “it’s hard to imagine him having not done that.”

“Alex Harsley: The First Light From Darkness” is on view now through August 22, 2021 at Pioneer Works.