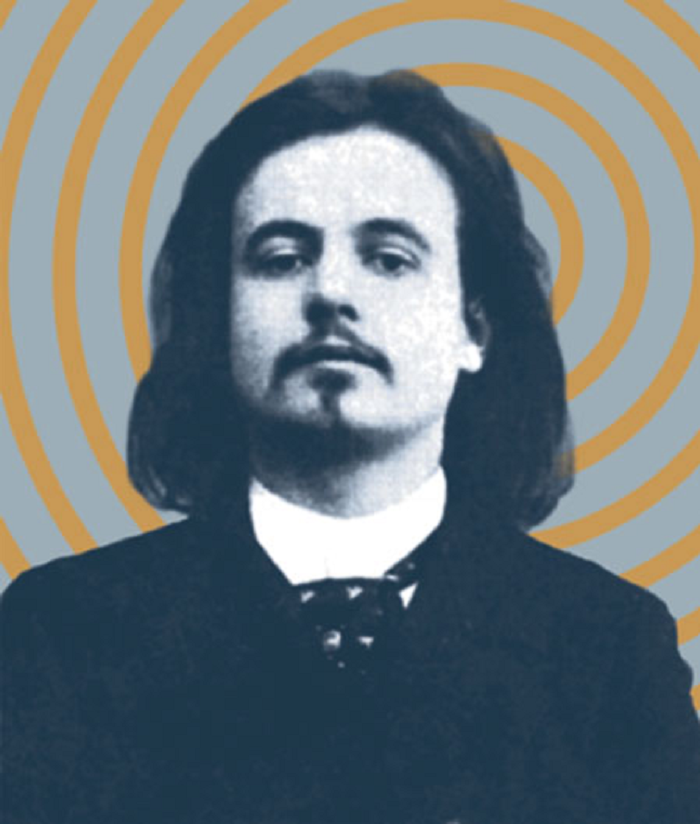

A portrait of the French playwright and legendary bohemian Alfred Jarry, with his long dark hair and manicured goatee that evokes The Three Musketeers, appears alongside family photos in Linda Klieger Stillman’s home in outside Washington, DC.

In fact, art and memorabilia related to the proto-Dadaist and inventor of “pataphysics” is scattered all over the house, though some of it is missing now that Linda and her husband, Robert Stillman, gave a significant gift of Jarry’s books and manuscripts to the Morgan Library. Those objects are on view there now as part in the new show “Alfred Jarry: The Carnival of Being,” through May 10.

On a recent visit to her home, Linda, who has been obsessed with Jarry for more than 40 years, was wearing earrings, a ring, and necklace in designs she associates with Jarry’s drawings, and the same emblem appears on a purplish hand towel in one of her bathrooms.

Stillman, who is part of the Collège de ‘Pataphysique, founded in Paris in 1949, first became interested in Jarry early on in her language and linguistics studies at Georgetown University. After completing a project on the language in Jarry’s most famous play, Ubu Roi (or King Ubu), her professor suggested she write her dissertation on the subject.

“I’ve had this entire Ubuesque and Faustrollian and pataphysical life ever since,” she says. (Dr. Faustroll was another Jarry character, based on Faust.) “I think he was the launch pad of the entire avant-garde of 20th-century Western culture,” she says.

Jarry’s grotesquely tyrannical King Ubu has recently reemerged with surprising relevance to today’s politics. Critics including Hal Foster and Charles Simic have described President Trump as a modern-day King Ubu, “who was a buffoonish pretender to the throne of Poland, a brutal and greedy megalomaniac who, after killing off the royal family, starts murdering his own population in order to rob them of their money,” Simic writes, noting that Ubu is the only literary character he knows of who approximates the president. Meanwhile, playwright Paula Vogel organized national Ubu “bake-offs” in 2018 to protest President Trump.

And what’s currently going in Ukraine and Russia is intimately connected to what Jarry wrote about in the Ubu, Stillman says. (She also believes Jarry’s writings anticipated some of Einstein’s theories.)

Alfred Jarry’s Ubu roi in Livre d’Art no. 2 (April 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum. Photo: Janny Chiu.

However, Sheelagh Bevan, the curator of the exhibition at the Morgan, says that Jarry’s life was more one of the imagination than of politics, and notes that the writer made very few political statements in his lifetime. “Jarry was too much of a pure artist and individualist to be nailed down by anything,” she says. “That sort of pure artistry would be difficult in the contemporary moment. It would be difficult to be that pure of an artist right now.”

Despite this renewed relevance, Bevan has been surprised by the public’s lack of familiarity with Jarry’s name, “even much less what his work was really about, and I’m not sure how to account for that,” she says. A museum director in France told her that even French people who use the term Ubuesque to mean something negative about power and authority don’t necessarily know that it comes from Jarry’s play.

“It has just become a term,” Bevan says. “’We’re hoping that this [show] will stimulate further scholarship and a broader familiarity with just how important he was.”

Historically, Jarry had more success finding his way into famous circles. Pablo Picasso and Pierre Bonnard both drew his portrait, and Paul McCartney was reading Ubu Roi in 1968 while composing The Beatles’ song “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” which opens with the lines “Joan was quizzical / studied pataphysical science in the home.”

Alfred Jarry and Claude Terrasse, Répertoire des Pantins: La chanson du décervelage (Paris: Mercure de France, 1898). Photo: Janny Chiu.

Artists from the Surrealists to Dadaists saw Jarry as their patron saint, which raises the question of how different modern and contemporary art history would be without Jarry’s pataphysics. (Certainly, there wouldn’t have been the rock band Pere Ubu.)

Bevan first learned about pataphysics in her 20s, and Jarry’s books, which she encountered in a Museum of Modern Art exhibition about artists’ books in the mid-1990s, made a “huge impression” on her. But his writings are difficult to read, and there are barriers in the availability of translations.

Pataphysics, in one translation, is “the science of imaginary solutions, which symbolically attributes the properties of objects, described by their virtuality, to their lineaments.” On a first read, that’s about as clear as mud. Merriam-Webster offers a simpler, if rather dismissive, definition: “intricate and whimsical nonsense intended as a parody of science.”

Performances are also tough to document, Bevan adds, particularly given how Jarry’s life imitated his art. Jarry adopted Ubu’s outlandish way of speaking. When describing his parents, for example, he said, “Our father was a worthless joker—what you call a nice old fellow. He no doubt made our older sister … but he cannot have played much of a role in the confection of our precious person. Our mother was a lady of Coutouly ancestry, short and sturdy, willful and full of whimsey, of whom we had to approve before we had a voice in the matter.”

Alfred Jarry (at right) fencing with Félix Blaviel in Laval, 1906, photograph. Courtesy of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Jarry’s life was brief, dramatic, and filled with plenty of controversy. In his short story “The Passion Considered as an Uphill Bicycle Race,” Jarry, who was an avid cyclist, imagines Jesus Christ bike-racing against some thieves and then wrecking on a turn. Jarry’s blasphemy, wrote Roger Shattuck in his 1968 book The Banquet Years, “transformed religion into a sport, just as the mechanical idea of the athletic record gave him the opportunity to victimize romantic love. … He said categorically, ‘Screw good taste.’”

And when King Ubu premiered, the first word uttered—merdre, a variation on the French word for “shit”—caused a scandal by voicing a curse word in formal theater.

A decade later, Jarry died, at just 34 years old, in part due to his heavy drug and alcohol habit.

Stillman with Ubu Tells the Truth by William Kentridge. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

The Morgan show is a corrective to Jarry’s better-known antics, Bevan says, by focusing instead on printed books. Visitors will discover Jarry’s collages, for example, which might juxtapose a 17th-century recipe for turning your hair green with a snippet of his own writing. “He didn’t care about tempering the various illustration styles,” Bevan says. “It’s an unorthodox approach to authorship in general.”

Taken together, the books go beyond Ubu to offer a deeper and more rounded look at Jarry’s oeuvre. “You just see so much more, and you see the serious side of the comedy,” she says.

This duality is what initially drew South African artist William Kentridge, who played the character of Captain Manure in his university’s production of King Ubu, to Jarry’s work. “There’s something about the absurd and the political absurd that intrigued me with Jarry which has stayed with me,” Kentridge says. He, along with two other South African artists, has since made Ubu-inspired etchings that explore “the combination of the burlesque and the grotesque, and the violent and the comic, that is the heart of the writing.” (Another painting that Kentridge made about Ubu hangs in Stillman’s home.)

Initially, Ubu adaptations in South Africa satirized apartheid rule, “but now it could also equally be done about the new rulers in the South African political arena,” Kentridge says. He credits Jarry with “understanding the absurd as a kind of political critique rather than the foolish or just the joke or the funny” and applying it as “a corrective, as a warning, as a demonstration of what happens when self-love and self-pity become the motivating factors of politicians.”