Amalia Ulman’s new solo show at London’s Arcadia Missa in Peckham, entitled “Labour Dance,” is at first very charming: Red balloons filled with helium and tied to sparkling ribbons crowd the ceiling, which, paired with dim lighting and two small flickering TV screens, set the room alight in a soft pink glow.

Designed as a durational piece, each element on display is part of the larger installation, including several beautifully crafted ceramic balloons, which upon first glance seem simply deflated and old, randomly scattered across the floor. The installation acts a continuation of “Privilege,” a work commissioned for the 9th Berlin Biennale and that was available to view online earlier this year.

Amalia Ulman, Privilege (2016). Photo Courtesy: Arcadia Missa.

“Labour Dance” gets its name from the trend of women dancing vigorously to induce labor, and its accompanying text is a series of comments from online forums about the same. (“I danced to get to 5 cm (cervical dilation) I put on tyga rack city and went crazy lol also a great way to squeeze in exercise :)” writes a user in an excerpt from a group chat on the website whattoexpect.com.)

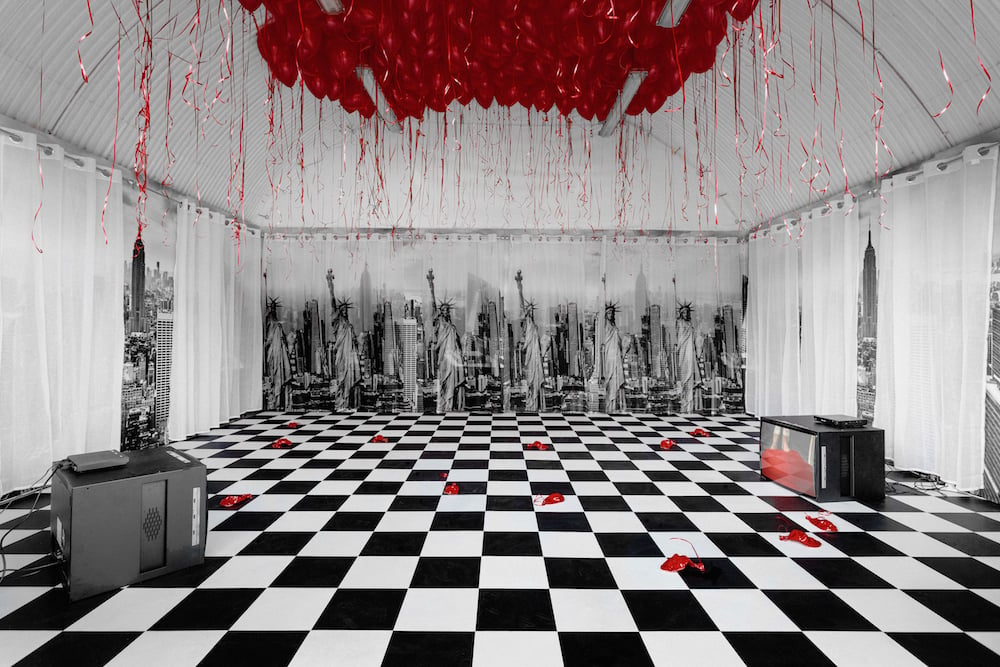

Lining Arcadia Missa’s cavernous walls are large photographs of the New York City skyline, only slightly covered up by sheer white curtains, and it is as though the scene is set in a rather expensive corporate office on Madison Avenue. Replete with skyscraper views and an ironic ’70s black-and-white chequered floor, it is a nod, perhaps, to the open-plan, “fail harder” work cultures of recent years.

In one of the TV screens we have Ulman herself, in a red dress bearing the swell of a pregnant belly, holding a bouquet of balloons in a shiny steel elevator, taking a video selfie in its opening doors. In another scene, Ulman, sat upon a swivel chair, slides in and out of an office lobby arms raised in the air, a large smile plastered across her face.

Installation Views of Labour Dance by Amalia Ulman at Arcadia Missa. Image Courtesy of the Artist & Arcadia Missa.

The artist is delightfully funny, humor delivered with a cheeky smile and an arm cocked jauntily over hip, without need for any Keaton-esque clumsiness or chaos. Viewers laugh out loud, as they do when Snapchats of pigeons with large heads totter across the screen, or when Ulman launches plastic water bottles with the hope of landing them perfectly upright every time. In this, there is a certain lightness to her work that allows for humor to seep in without pretension or cliché.

At the opening, with the promise of seeing Ulman herself, the gallery space spilled over with excited young girls, “As a first-year student on the Goldsmiths Fine Art BA, it is almost a prerequisite to be totally obsessed with Amalia and her work,” declared one to artnet News. What is almost immediately clear is the intimacy generated between Ulman and her fans, following her, as they do, very closely on social media.

Dressed on the night in a long red coat and red platform boots, Ulman is stunning, standing out from the crowd with a shy and endearing charm. There is of course a discrepancy—and one that is easy to confuse—between Ulman herself and her on-screen performance, which plays out through her various social media channels, as well as through her works spanning film, poetry, video essay, and collage. Her Instagram is most famous of all, visited by followers upwards of 126,000, which was featured in the work Experiences & Perfections at the Tate Modern’s “Performing for The Camera” group show this year.

Amalia Ulman, Excellences & Perfections (Instagram Update, 8th July 2014),(#itsjustdifferent)(2015). Image Courtesy of the Artist and Arcadia Missa.

In a sense, Ulman has pioneered the use of social media as performance, as total artwork, and juxtaposes this contemporaneity with the use of nostalgic objects, like the chunky TV screens placed at random upon the floor.

But there is of course the subtext of celebrity, and of identification, which Ulman handles effortlessly—her position of access and privilege is highlighted by her mocking tone, and her delight in indulging the erratic. Ulman is entirely aware that it is indeed her privilege to be in a position to critique and complain, and in doing so she exposes the political lines that are ultimately marshalled by the art world in its entirety.

While questions of her pregnancy circled the gallery floor, it is exactly in such detail that her work delivers its poignant punch: as viewers, we are too often engaged in the confusion of the public and the private persona, something Ulman negotiates with the introduction of her “pet” pigeon Bob.

In an interview with artnet earlier this year, she explained Bob’s appearance in her art, saying “I’m currently working on a narrative where I developed a character for myself, based on people’s projections and preconceptions about me, and I also developed the role of a sidekick and counselor, a pigeon that sneaked into my office in Downtown LA and who stayed until becoming a very important character in the story.”

Amalia Ulman and Bob the Pigeon. Image Courtesy @amaliaulman Instagram.

“Labour Dance” is ultimately a critique of the aesthetics of power and position, and for this, it has developed its own special language and performative play. It is most effective in highlighting that the critical position it occupies it not accessible to all, and set deep under the rumbling railways arches of a fast-gentrifying Peckham, the irony is not lost on many.