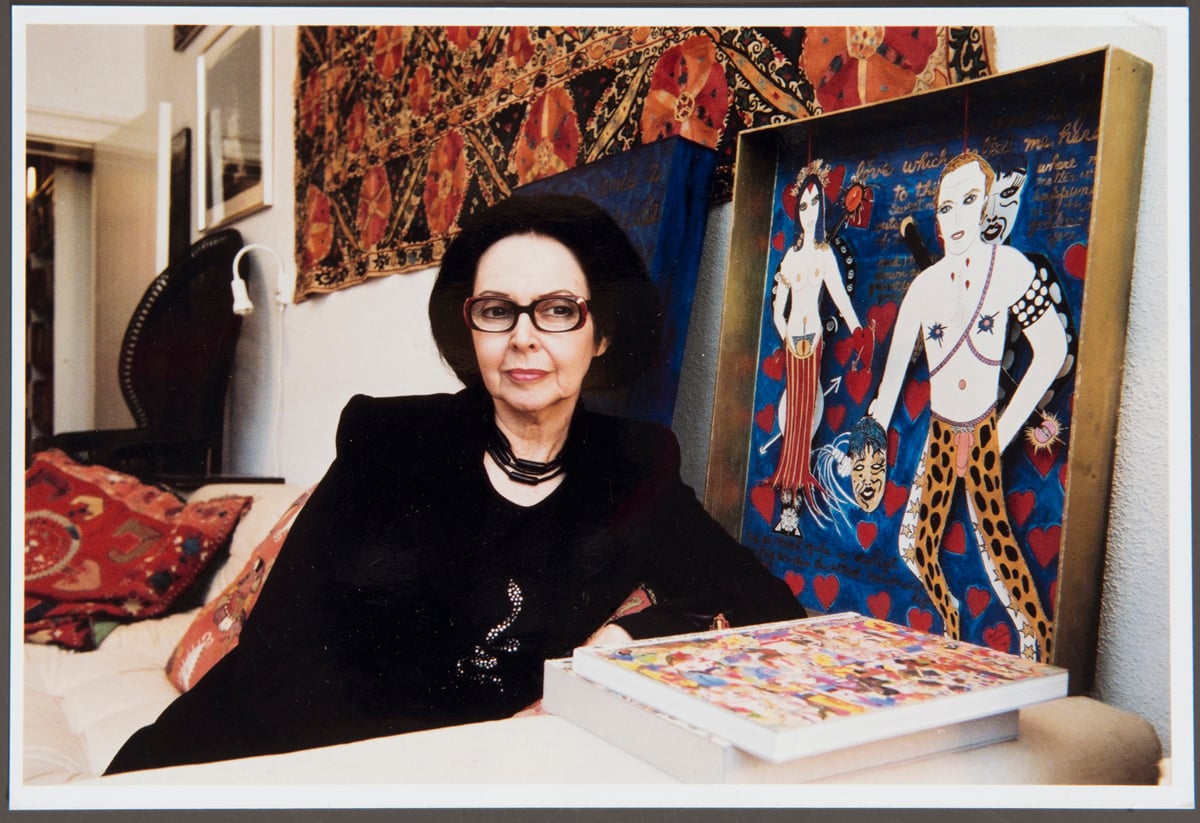

Dorothy Iannone, the America-born, Berlin-based artist who created explicit, joyful, and indelible art about sexuality and pleasure, has died. She was 89. Her death, after a short illness, was confirmed by her Paris gallery Air de Paris.

“Love and freedom has been at heart of Dorothy Iannone’s work for six decades, with full force until her unexpected death yesterday,” the gallery said in a statement. “We will deeply miss her as an original artist, an intellectual and engaged human being, a most loving, fun, and compassionate friend.”

Throughout her long career, Iannone worked across media, jumping from painting, drawing, and collage to video, sculpture, and artist’s books. The through line was an exploration of female sexuality, desire, power, and liberation. Adept at blending text and imagery, she became known for a colorful and graphic aesthetic that drew from Indian erotica, Japanese woodcuts, Byzantine mosaics, Egyptian frescoes, and American comic books.

While some female artists object to having their art read through the lens of their personal life, for Iannone, the two were inextricably linked. In her life and work, she sought to fight censorship, follow her heart, and reject society’s expectations.

Dorothy Iannone, I Lift My Lamp Beside the Golden Door (2018). Photo by Timothy Schenck. Courtesy of Friends of the High Line.

Born in Boston in 1933, Iannone was raised largely by her mother; her father died when she was two. She studied literature at Boston University and Brandeis but gave up a doctoral fellowship at Stanford to marry James Upham, a painter and wealthy investor.

As the two became fixtures of the downtown New York art scene and traveled the world, Iannone began making cutout wooden portraits of famous figures like Charlie Chaplin and Jacqueline Kennedy. While she also worked in the Abstract Expressionist style popular at the time, seeds of her future interests were evident, primarily in the form of plainly visible private parts on even her fully clothed cutout characters.

Iannone made headlines in 1960 when U.S. Customs seized her copy of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer at an airport in Queens. She went on to sue the organization successfully with the help of the New York Civil Liberties Union, which resulted in the government lifting the ban on Miller’s work.

The biggest turning point in her life and career came seven years later, when she met the artist Dieter Roth on a trip to Iceland. Within a week, she made the decision to leave her husband and move to Reykjavik to be with him. She described him as her muse; he called her his lioness.

They became prominent figures in the Dusseldorf Fluxus movement, remained lovers until 1974, and stayed close friends until his death in 1998. She moved to Berlin on a scholarship in 1976, and lived there until her death.

Dorothy Iannone, Wiggle Your Ass For Me (1970). Image courtesy Air de Paris, Paris.

It was during her relationship with Roth in the 1970s that Iannone made some of her most famous—and explicit—works. Portraits of herself and Roth in flagrante delicto were adorned with stars and flowers. She created an artwork documenting everyone she had ever slept with many years before Tracey Emin became famous for doing the same.

Of her creatively fertile relationship with Roth, she told Maurizio Cattelan in an interview for Flash Art: “The two of us became the stars of my work, and instead of using lines from poems which I loved in my paintings, now I recorded what we had said to each other, or I wrote my own texts. No longer was I obsessed with the high love of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, now I had found my own, and in the course of recording it—not only the ecstasy but the domestic scene too, and the difficulties—my work went into many new directions and took on many new forms.”

The video sculpture I Was Thinking of You III (1975) is another key piece in Iannone’s oeuvre. A human-scale box painted with an erotic scene, it contains a built-in monitor with a video of the artist’s face as she masturbates. It was this work that elevated Iannone’s profile in the mid-2000s, when it was remade for the Wrong Gallery at Tate Modern in 2005 and the Whitney Biennial in 2006.

“I am always embarrassed when I see this film, even if no one is with me,” the artist said in the Flash Art interview. “I wonder how I could have made it but I’m so glad I did.”

It took a while for the art world to catch up to Iannone. Some considered her work indecent; others deemed it not sufficiently feminist, given its focus on sex (and hetero sex at that).

Dorothy Iannone, On And On (1979). © Dorothy Iannone

Over the past 20 years, new generations of curators and artists have found and celebrated Iannone’s work. She was the subject of solo shows at the New Museum in 2009, the Camden Arts Center in London in 2013, and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark earlier this year. She is represented in the collections of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, and many others.

As her friend, artist Jan Voss, once wrote, “Dorothy has been for all the time I’ve known her an incarnation of all revolutionaries. She determined herself which hierarchy she would acknowledge and which to laugh away.”

In 1969, her work was censored from a forthcoming exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern, whose director demanded that the genitals in her paintings be covered. (Roth removed his work from the show in protest, and curator Harald Szeemann resigned.) She made a comic book about the experience titled The Story of Bern (or) Showing Colors (1970). As always, for Iannone, everything was raw material.