The word “handscroll” in Chinese consists of the characters “hand” and “scroll,” which best describe the manner of viewing this structure. The handscroll is made up of a long, horizontal sheet of paper. To its left end, a wooden roller is attached. When the scroll is not on view, the entire paper is rolled up, and tied with a fastener at its right end. Layers of papers and decorated silks together served as the backing to support the centerpiece—the painting or calligraphy that was mounted on top.

Diagram of a handscroll

Unlike an oil painting that is hung on the wall and meant to be appreciated from a distance, the handscroll is designed to be held in the hands and unrolled section by section to reveal the full image. The viewing is by its nature an intimate experience. As you unfold the composition from right to left, your left hand slowly unrolls the scroll while your right hand loosely rolls it up, maintaining a viewing section of a comfortable length.

Lu Yanshao, Reading room, 1962

This format is favored by the ancient Chinese Art practices for various reasons. Firstly, the long paper reel buffers environmental intrusions such as dust, mould, or dampness, from threatening the painting. Secondly, a rolled-up handscroll takes up little space and is utterly portable. Early Buddhist scriptures found in the Dunhuang Caves (8th–9th century CE) were mounted in handscrolls so that the monks could carry the sutras with them to recite anytime. In later times, artists in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) use this art form in their frequent “elegant gatherings.” In these gatherings, which served as a kind of art salon and were usually held outdoors, painters and poets improvised paintings and calligraphies and recorded their works on the handscrolls.

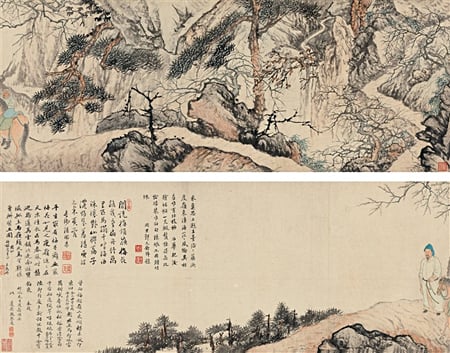

Shi Tao, A man with a horse in the mountain

Most significantly, the format of a handscroll enables a bibliographical reading of the painting. The extended paper sheets attached in front and after of the painting provide platforms for the owners and/or viewers to leave their commentaries on the handscroll. Vestiges in the forms of frontispiece, colophons, and seals demonstrate the ownership, connoisseurship, and scholarship with the painting.

It is not known whether the horizontal painting defined the handscroll format, or the virtues of handscroll popularized the horizontal type. But landscapes are perhaps most commonly met with since they are most suited in presenting as one continuous picture on a long, narrow roll.

Tang Yifen, Leisure Travel in the Water Village

The landscape paintings in the format of handscroll can be read as a complete narrative. It intrigues you with pictorial plots, and surprises you with the forwarding of the narrative. Just like reading a book, you are tempted to explore the exquisite details, and urged to turn to the next page, or the section of painting, to be able to enjoy it in full. Not only competent in presenting the linear narrative but also in the transcendental spaces, the handscroll painting is in turn often compared to the screening of a film. However, instead of being forwarded automatically, the pace and direction of proceeding can be controlled actively by the viewer. The tradition of over 1,000 years continues to thrive in the innovative interpretations of the young Chinese artists.