Andy Warhol famously instructed an interviewer to “just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” But it’s been a long time since the pioneering Pop artist has been seen simply as an empty cipher. In the years since his death in 1987 Warhol has been reborn many times. The ever-multiplying Andys include social critic Andy, queer Andy, proto-postmodern Andy, reality TV Andy, and commercial Andy.

“Andy Warhol: Revelation,” currently on view at the Brooklyn Museum, homes in on Catholic Andy. Originally organized for the Warhol Museum by its chief curator José Carlos Diaz and overseen in its Brooklyn incarnation Carmen Hermo, the exhibition draws a line from Warhol’s religious upbringing as a Byzantine Catholic (he later took up Roman Catholicism) through the twists and turns of his career to his last major undertaking, a set of over 100 paintings based on Leonardo’s Last Supper.

This is touted as the first exhibition to explore this aspect of Warhol’s work. However, it is not exactly a new take—the catalogue references both art historian John Richardson’s paean to Warhol’s “secret piety” in his 1987 eulogy and Jane Daggett Dillenberger’s 1998 tome The Religious Art of Andy Warhol.

I will modestly add here the chapter I devoted to Warhol’s Catholicism in my 2004 book Postmodern Heretics: The Catholic Imagination in Contemporary Art. Another precursor is Arthur Danto, whose ideas about the transfiguration of the commonplace hover without attribution in labels that discuss Warhol’s sculptures of Heinz Ketchup and Delmonte Peaches boxes.

Installation view for “Andy Warhol: Revelation, at the Brooklyn Museum, November 19, 2021-June 19, 2022. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. Artworks by Andy Warhol © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. /Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

But if the idea of a Warhol immersed in spiritual concerns has been around for some time, newly unearthed materials from the archives of the Warhol Museum have deepened the case. Discoveries include an unfinished film that would have been funded by the Catholic Church, a never completed series of images of nursing mothers, a set of drawings of angels by Warhol’s mother Julia Warhola, as well as religious objects, letters, and clippings that give context to the snippets of text and found images that appear in Warhol’s paintings.

In addition, the show leans heavily on recent scholarship by Warhol Museum curator Jessica Beck that places Warhol’s late Last Supper paintings in the context of his terrified response to the concurrent AIDS Epidemic. These materials, combined with revelations first made by Richardson of Warhol’s regular church attendance, his financial support of a nephew’s studies for the priesthood, and his participation in a soup kitchen provide a picture of Warhol much at odds with more familiar representations of the artist as an indifferent societal mirror or cultural sieve.

Installation view for “Andy Warhol: Revelation, at the Brooklyn Museum, November 19, 2021-June 19, 2022. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. Artworks by Andy Warhol © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. /Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The show opens with a wealth of materials that underscore the degree to which religion saturated Warhol’s childhood. On display are holy cards, religious statuettes, and crucifixes from his home, several religious paintings borrowed from his childhood church, and even a painting by a very young Warhol in which his childhood living room is presided over by a prominent cross.

The show then builds its case with thematic sections that consider other aspects of Warhol’s debt to Catholicism. One set of works and ephemera consider his rather problematic relationship with women. These include his obsession with Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy, whose portraits have long been seen as counterparts to the Byzantine icons of his childhood; his friendship with Candy Darling, Warhol superstar and transgender icon; and his near assassination by Valerie Solanas, the Factory hanger-on and author of the SCUM Manifesto (a piquant acronym for the Society for Cutting up Men).

More surprising are drawings and photographs depicting breastfeeding mothers. Inspired, presumably, by the countless Renaissance paintings of the Madonna and Child, these were intended for a never realized painting series.

Installation view for “Andy Warhol: Revelation, at the Brooklyn Museum, November 19, 2021-June 19, 2022. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. Artworks by Andy Warhol © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. /Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Another section documents Warhol’s 1980 visit to the Vatican and his five-second meeting with Pope John Paul II amid a throng of other worshipers. The exhibition ties this to a number of Warhol drawings of huge crowd scenes. A section documenting his borrowings from various Renaissance paintings (and pointing toward the late Last Supper paintings) tries to make the case for Warhol as a latter-day Renaissance man.

A section of an unfinished film originally destined for a 1968 World’s Fair in San Antonio is comprised of poetic images of the setting sun accompanied by a crooning voiceover by Factory chanteuse Nico. Commissioned by the Catholic Church, it bears a striking resemblance to Paul Pfeiffer’s 2001 film Study for Morning after the Deluge, in which the rising and setting sun also becomes a metaphor for the cycle of life and death.

But most crucial for the exhibition’s argument is a section titled “The Catholic Body.” Here the show ties the essential carnality of Catholicism, a religion whose doctrines, art, and literature center on very literal representations of the “Word Made Flesh,” to Warhol’s bodily obsessions and his conflicted existence as a gay man in a faith that condemns homosexuality.

Installation view for “Andy Warhol: Revelation, at the Brooklyn Museum, November 19, 2021-June 19, 2022. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. Artworks by Andy Warhol © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. /Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Two works introduce these ideas. Richard Avedon’s iconic photograph of Warhol’s bared torso riven with the scars left by Solanas’s attack becomes, in this context, a modern-day version of the many Renaissance representations of the martyr Saint Sebastian, whose muscular arrow riddled torso has made him a gay icon.

A lesser known Warhol silkscreen painting from 1985–86 titled The Last Supper (Be a Somebody with a Body) also presents a juxtaposition of religious and homoerotic imagery, this time by layering images of the Christ from the Last Supper and an image, clipped from a newspaper ad, of a buff, half-dressed body builder.

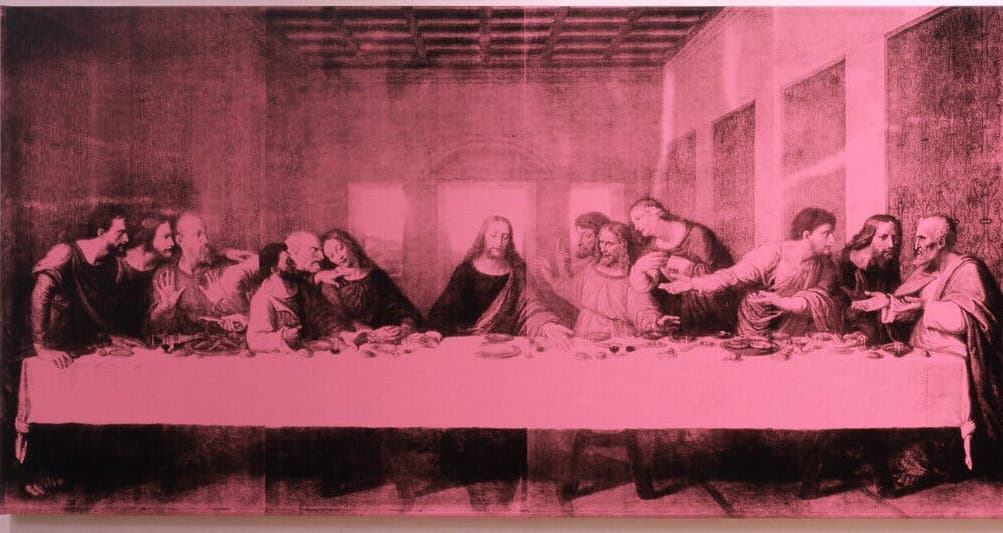

Which brings us to the exhibition’s centerpiece. “Andy Warhol: Revelation” pivots on Warhol’s Last Supper paintings. Arranged like a horseshoe, the layout leads one through the above-mentioned material to a voluminous quantity of Last Supper imagery. The Last Supper paintings were commissioned in 1984 by art dealer Alexander Iolas for display in a space in Milan across the street from Leonardo’s masterwork.

But Warhol went far beyond the confines of the original commission. He collected multiple images of the Last Supper, including a lenticular version and a very kitschy sculptural rendition documented here in polaroid photographs. And he used the imagery in many ways, including on a series of punching bags that were collaborations with Jean Michel Basquiat and in paintings emblazoned with logos or comprised of fragments of Leonardo’s mural.

Installation view for “Andy Warhol: Revelation, at the Brooklyn Museum, November 19, 2021-June 19, 2022. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. Artworks by Andy Warhol © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. /Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

At the Brooklyn Museum, two full-scale versions of Warhol’s Last Supper are presented in an almost chapel-like space. They spread over opposite walls separated by a bench where, on the day I visited, visitors were obediently sitting in contemplative silence. This is a reminder of the ambiguity embedded in this work—and for that matter, all of Warhol’s work.

Depending on which Andy they are highlighting, critics have tended to locate Warhol’s imagery on a scale that runs from blank irony to heartfelt sincerity. The Last Supper paintings pose a particular problem. Are they just another pop culture image, not unlike the like soup cans, dollar signs, or portraits of Chairman Mao, appropriated precisely because of their ubiquity and banality? Or are they vessels full of personal meaning?

In an essay referenced in the catalogue, Jessica Beck makes the case for the latter, arguing that these late paintings were created in an atmosphere suffused with the threat of AIDS. Many of Warhol’s friends and associates were dying of the disease. In response, Beck maintains that Warhol “gave AIDS a face—the mournful face of Christ.”

Installation view for “Andy Warhol: Revelation, at the Brooklyn Museum, November 19, 2021-June 19, 2022. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. Artworks by Andy Warhol © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. /Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

And yet, as the exhibition now moves down the other prong of the horseshoe layout, closing the show out with works that provide a Catholic context for some of Warhol’s more familiar imagery, one can’t help feeling that interpretation is a little too pat. The exhibition consciously resists the tendency, evident both in the Richardson eulogy and the Dillenberger study, to present an overly sanctified Warhol free of the bedeviling contradictions that continue to make him such an elusive subject. But at the same time the approach here seems overly hermeneutic.

By that I mean that texts and images are treated like hidden messages to be deciphered as one might the theological exegeses embedded in Renaissance religious paintings or medieval manuscripts. Such an approach seems to dismiss the deliberate insouciance of Warhol’s own commentaries as well as the obvious ironies that underlie so many works. And it makes it necessary, to use just one example, to reframe the overtly blasphemous and sacrilegious references in Warhol’s film Chelsea Girls, screened in full here, as modernizations of Christ’s embrace of outcasts and misfits.

Installation view for “Andy Warhol: Revelation, at the Brooklyn Museum, November 19, 2021-June 19, 2022. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. Artworks by Andy Warhol © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. /Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

It seems more true to the Last Supper paintings to acknowledge that they exist, like all Warhol’s works, in a continuum between irony and sincerity, partaking simultaneously of both. Warhol could be both vulnerable and cruel, spiritual and profane.

Perhaps it might have helped to delve a bit more into the contradictions between the carnal and the spiritual inherent in Catholicism itself. The section “The Catholic Body” starts to do this, but doesn’t touch on the homoerotic overtones of Catholic stories and imagery that would have fired Warhol’s imagination. This is, after all, a religion whose central image is a near naked man on a cross.

Warhol was not alone in finding the mix of ritual, sensuality, and homoeroticism in Catholicism irresistible, even as its official dogma condemned his sexual being. Robert Mapplethorpe, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and David Wojnorowicz are three gay artists whose work is increasingly being considered in terms of their Catholic upbringing. Of particular relevance to this exhibition is the way that Wojnarowicz used the face and body of the crucified Christ to denote suffering and to evoke society’s callous disregard for the ravages of AIDS while also roundly condemning the Catholic Church’s complicity in the crisis.

Installation view for “Andy Warhol: Revelation, at the Brooklyn Museum, November 19, 2021-June 19, 2022. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. Artworks by Andy Warhol © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. /Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Moving on from the Last Supper sanctuary, the show winds down with sections that bring us some of the more familiar aspects of Warhol’s work. In light of what has gone before, these now also take on a Catholic tinge. The “Skulls,” “Shadows,” “Electric Chairs,” and “Death and Disasters” evoke Warhol’s death obsession. A section titled “The Material World: What We Worship” offers a nod to his valorization of consumption, now seeing Warhol as the chronicler of “the desires, hopes, and prayers of modern life.” One series, “Guns, Knives, and Crosses” from 1981-81, makes a particularly ambiguous statement about the relationship of religiosity and violence.

Whatever its shortcomings, this is a thought-provoking and deeply researched show. And, given the way it foregrounds the tension between Warhol’s homosexuality and his Catholic faith, it must be added that it is also a brave one. These days it is easy to raise the censorious hackles of cultural arbiters from both ends of the political spectrum. By presenting a frank acknowledgement of the complexities of sexuality and faith, Andy Warhol: Revelation opens up new avenues in the often fraught discussion of the relation of art and religion.

“Andy Warhol: Revelation” is on view at the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, November 19, 2021–June 19, 2022.