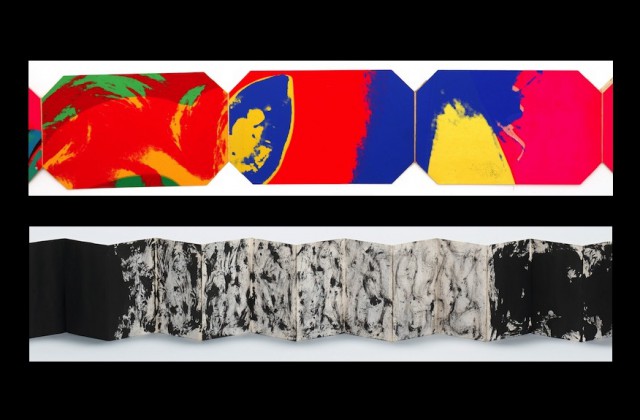

THE DAILY PIC (#1306): The top work in this image is a detail from a maquette for a unique, almost unknown accordion-fold book by Andy Warhol, probably from early 1968, found buried in one of his Time Capsules at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh (and here shown flattened out; see below for it folded). The bottom work is a detail from an accordion-fold book by Yoko Ono which was shown in 1961 in her first solo show, at George Maciunas’s AG Gallery in New York. It was titled Painting Until It Becomes Marble, and came with the instruction that visitors were to “cut their favorite parts until the whole thing is gone”. The Warhol piece is now at the Williams College Museum of Art, in the “Warhol By the Book” show that I’ve already written about for this column; the Ono will be in the survey of her early art that opens at MoMA on May 17, and that I wrote about in yesterday’s New York Times. And the reason both are in my Pic today is that I think they may be related.

Each of the 38 pages in Warhol’s accordion book is made from a lozenge-shaped detail that he had die-cut out of his famous edition of Marilyn prints from 1967, using the same tooling used to cut the big labels stuck on the box the edition came in. (Last night, I asked the collector Rob Roth to measure the rare box-labels he owns, and they match the book’s dimensions precisely; scroll down to see the labels.)

In his essay in a book called Reading Andy Warhol for the “By the Book” catalog,[corrected 05/12/2015-bg] co-curator Matt Wrbican – a living hard-drive of all things Warholian – does an immaculate job of spelling out everything that is known or can be guessed about the maquette, including spotting exactly where each of the details was cut from in the original prints. He points out that Warhol went to some trouble to avoid using almost any passage where you could easily recognize that the source image was a portrait. As Wrbican shows, Warhol made sure that one of the most famous faces of all time got turned into a series of almost unrecognizable patterns – into pure modernist abstraction, of the kind that still reigned in much of the art world even in 1967.

And that’s where the Ono book comes in: As soon as I saw it, I realized that it could have been an inspiration for Warhol’s piece. We have no record of Warhol having visited her show, but we do know that, for several years before he himself became a notable artist, he was deeply interested in the radical Downtown scene that she was part of, and made a point of frequenting its events; given his voracious appetite for the new in art, and his unfailing radar for what (and who) was worth seeing in New York, it seems likely he would have made it to the AG show; we know his hero John Cage did, and where Cage went Andy was likely to follow. (Warhol had known Cage and his work since high school; later in the 1960s, at least, he also got to know both Maciunas and Ono.)

If Warhol did see Ono’s accordion book, it would have had a special significance as a model. It was evidently abstract, and Warhol had felt a powerful pull toward abstraction – and had mounted a fierce resistance to it – at least since his college years. (He was mirroring a conflicted relationship to abstraction that the entire Pittsburgh art world had shared; some of his college instructors were the city’s first and fiercest abstractionists, while others were diehard depicters.) Given that Yoko’s book was by a notable young radical, however, and on view in the cutting-edge AG Gallery, its abstraction had a conceptualist aura and context. And that moved it beyond the purely formal gamesmanship that Warhol – and his best peers – had sensed was hitting a wall at that time.

Warhol’s own accordion book strikes the same balance as Ono’s: It registers as potent abstraction, but has such a rich backstory – and such deep ties to our everyday world – that it can never be dismissed as so much attractive design.

By slicing and dicing two icons at once – the face of the great movie star, and the surface of a great Pop art masterpiece – Warhol, you could say, makes his version of Ono’s famous Cut Piece performance, but where he’s both cutter and cut-ee. (Warhol image: The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Ono image: Private collection)