Image: Courtesy of the artists.

This is the third in a four-part series in which Anthony Haden-Guest engages Street artists in dialogue about their practice from the 1960s to today. (For more in this series, check out the first and second parts).

Making a Living v. Making a Life

The world of Street art has matured into a place where it is possible not only to establish a presence but also to make a pretty good living. Just like that other art world, there are collectors, commissions, and shows at galleries and museums. And in June 2014, Google launched a Street art database. But there are also great differences, some of which are rooted in history. The work of the breakthrough generation, who used spray cans to tag the New York subways in the 1970s, was called graffiti. Some, like Rammellzee and Phase 2, found the word patronizing. But then again, the words Cubism and Fauvism had begun as insults too. Like those epithets, it stuck.

Then artists started wheat-pasting. It was a venerable, labor-saving form – that was how Toulouse Lautrec posters had been put up. A single stencil could be ubiquitous and in the 80s, the street art duo known as Cost and Revs blanketed New York with their tags.

Relations between old school graffiti artists and the new generation can be acrimonious, and even—especially in the UK—violent. Also, the commercial success of the phenomenon has brought into being a third group, sometimes called the “muralists” who are disdained by all.

Much Street art nowadays is permitted, indeed encouraged. But when it isn’t, it isn’t. Kenny Scharf was busted for tagging in 2013. Michael Bloomberg, former Mayor of New York, pushed the NYPD—unsuccessfully—to nail Banksy. This summer, Shepard Fairey had to turn himself in to the Detroit police for illegal tagging. Why do successful artists take the risk? Simple question, simpler answer. Risking life, limb, and liberty is how it all began. And it’s how to keep it honest, still.

Faile at work.

Image: Courtesy of the artists.

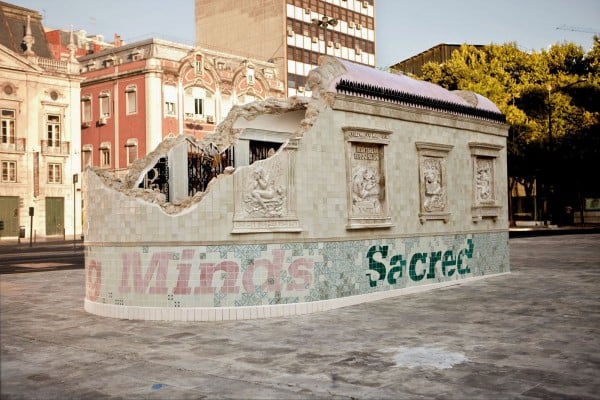

Making a career and keeping it real is the trick. That’s where risk comes in. And that’s how a new name gets established. Faile have been working together in New York since the late 1990s on projects including an installation at Lincoln Center. You can see their exhibition “Savage/Sacred Young Minds” at the Brooklyn Museum through October 4.

AHG

When did you realize that you had reached a kind of stable position in your career?

Patrick McNeil of Faile

It was really the prints that exploded in 2005, 2006, 2007. That really freed us to do any extra-curricular work. It was the prints that really set us free and allowed us to produce art full-time.

AHG

If somebody like Target offered you a contract would you do an outright commercial project? I’m not attacking that, by the way.

Patrick Miller of Faile

I don’t think so. We’ve always tried to hold our cards pretty close to the chest. If a collaboration makes sense and it rings true to our ideas and our work, we are always open to collaborations and ideas. But as far as large-scale commercial, there’s nothing that really—

Patrick McNeil

—And one thing that has been more and more interesting over the years, too, is how do you find funding to do larger and larger projects that you want to do? So, it becomes more interesting to work with corporations. But when you are selling their thing and it’s not true to your artwork, or your vision, that’s where you draw the line.

Faile installation at Lincoln Center.

Image: Courtesy of the artists.

AHG

In 2013, you were commissioned to make an installation by the New York City Ballet because you have quite a following. Can you communicate with your following?

Patrick Miller

When you get to a certain point, it’s easy for base collectors to reach out to us, to be in contact. Earlier, we were doing some of that web stuff. Now we are using Facebook more.

Mint & Serf Ace Hotel commission.

Image: Courtesy of the artists.

Mint (Mikhail Sokovikov) and Serf (Jason Wall) have a street practice, and a studio practice as well. Working with corporations was not problematic for Mint and Serf.

Serf

We’ve done a lot of corporate stuff. We had Red Bull sponsoring us. We’re good friends with them still. We made money. And they showed work.

Mint

We came up with the hip hop culture. And that became pretty big. So graffiti, being associated with popular culture, kind of guided all these marketing people towards us. They wanted to encapsulate graffiti and use it for their marketing strategies and campaigns, etc. We got lucky because we were in the right place, New York City. There’s nowhere bigger in advertising and marketing than New York City. And they started recognizing us because we were hanging out Downtown at the same bars that the marketing people hang out at—Max Fish.

Serf

Marketing people, designers creative—it’s a small circle. Also, our graffiti was really recognizable. Our friends could easily identify it. They would see it and say, “That’s Mint and Serf!”

Mint

In the beginning, we would go to the Bronx and Queens and Staten Island—the different boroughs—but at some point, we were getting captured by the downtown nightlife. We would spend so many nights downtown in the East Village, on the Lower East Side, Chinatown, we were doing so much graffiti in those neighborhoods. And these marketing people lived down there so they were constantly confronted with our graffiti. So we started making money by combining our graffiti with other things that we liked doing.

Mint

There’s a guy, I don’t know how old he is, but he’s definitely not from New York. He’s out here, painting, where he’s rappelling down the sides of buildings—

Serf

—right in the middle of the building, he starts painting—

Mint

—like thirty feet down—

Serf

—doing graffiti. Very impressive!

Mint

He writes “ELMS.” He hasn’t done a lot of spots. But the three or four spots that he’s done so far in New York—I don’t know that he’s still here—they are incredible. I mean, they are just in the middle of a building. The only way is to literally harness yourself and rappel down. That to me is more—

Serf

—That’s way more ballsy than doing the trains.

AHG

What about commissions? Didn’t you do something for the Ace Hotel a few years ago?

Mint

We curated a bunch of rooms for them.

AHG

So you have no problem with commercial projects?

Mint

It’s a case by case thing. It has to have meaning behind it. There has to be a context. The last commercial project we did was with the New York Yankees and they have never done that with anybody else. They are a clean-cut company. In general, we shy away from commercial collaborations.

Stik, installation in Miho, Japan.

Image: Courtesy of the artist.

In 2014, Stik was in Manhattan to create a piece on a water tower just off Union Square.

AHG

How do you feel about taking on paid commissions?

Stik

I won’t do corporate gigs. I did a piece on the side of a lunch club in Berlin. In Kreuzberg. I don’t usually do commercial establishments but Kreuzberg is one of those boroughs like Hackney which is under threat from gentrification. So I wanted to support it.

AHG

The water tower is legal—someone came up with a permit. But is one of the most difficult aspects of that work?

Stik

It was so hot up there, I started to worry about my safety. Sometimes I get so tired I start making silly mistakes. There’s a gap (in the scaffold) and I worry about making a little mistake and just falling to earth.

AHG

That could happen?

Stik

There’s always a risk when you’re painting up high. Climbing up and “reaches.” A reach is up high. I’m considered a Street artist by graffiti artists. There’s that whole strong distinction. But I at least get kudos for getting a lot of reaches. I got one very illegal reach on a factory chimney. I used a six-meter-long aluminum pole with a paintbrush on the end of it to paint. I leaned out over a massive drop straight onto a car park. I was painting from midnight till 6am when the sun comes up. Because then of course everyone can see you. And the police passed every hour on the hour after six. Yeah, that was a very dangerous and illegal piece that I did over there. This one is just logistically dangerous.”

AHG

You’ve had run-ins with the cops?

Stik

In London, when the Council paint out graffiti they put black squares over it. So everywhere you look when the Council have been there all the graffiti has gone and there’s just a load of these black squares. One night I took out a can of white paint and a paintbrush and I went and put white windows on all of the black squares. So it looked like a city-scape. And the police saw me and chased me. I was on my bike, on my pushbike, and I cycled up a ramp when I thought, ”What the fuck am I doing? I’m going into the police station. They are going to catch me for sure.” So I kept pedaling down to the end of the train platform, threw my bike into a ditch, and carried on running down the train track and over a bridge into a towpath. I kept running and running and running. And I lost the police.

Related stories:

Anthony Haden Guest’s Intrepid Lives of the Street Artists, Part I

Anthony Haden Guest’s Intrepid Lives of the Street Artists, Part II

Jeffrey Deitch Is Curating for Property Developers on Coney Island