In 1874, the Bergen Museum on Norway’s southwestern coast appointed its first archaeologist and conservator. Though only 28 years old, Anders Lorange was making a name for himself by searching for Viking sites around the country and had notably excavated Raknehaugen, a burial mound on the outskirts of Oslo in 1869.

Newly employed, Lorange sailed from Bergen up the coast to Nordfjordeid where he planned to open the largest of the five burial mounds on a farm called Myklebustgarden. There, Lorange discovered the remains of a 100-foot-long Viking ship that had been burned 1000 years earlier as part of an elaborate funeral ritual. The Myklebust remains the largest Viking ship ever found in Norway.

Although both the size of the ship and the quality of the artifacts it contained pointed to a 9th-century Viking king, ultimately only half the site was excavated. The discovery of well-preserved and fully intact Viking ships in the proceeding decades meant the Myklebust was almost forgotten with interest only revived in the 1990s—in 2019, boat builders in Nordfjordeid completed a realistic reconstruction of the Myklebust and launched it into the fjord.

Anders Lorange’s business card marked with the note to his girlfriend. Photo: University of Bergen.

Recently, archaeologists from the University of Bergen have returned to re-excavate the Myklebust ship partly in the hope of placing it on Norway’s tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage sites. Lorange, the researchers discovered, had left them some notes to pick over.

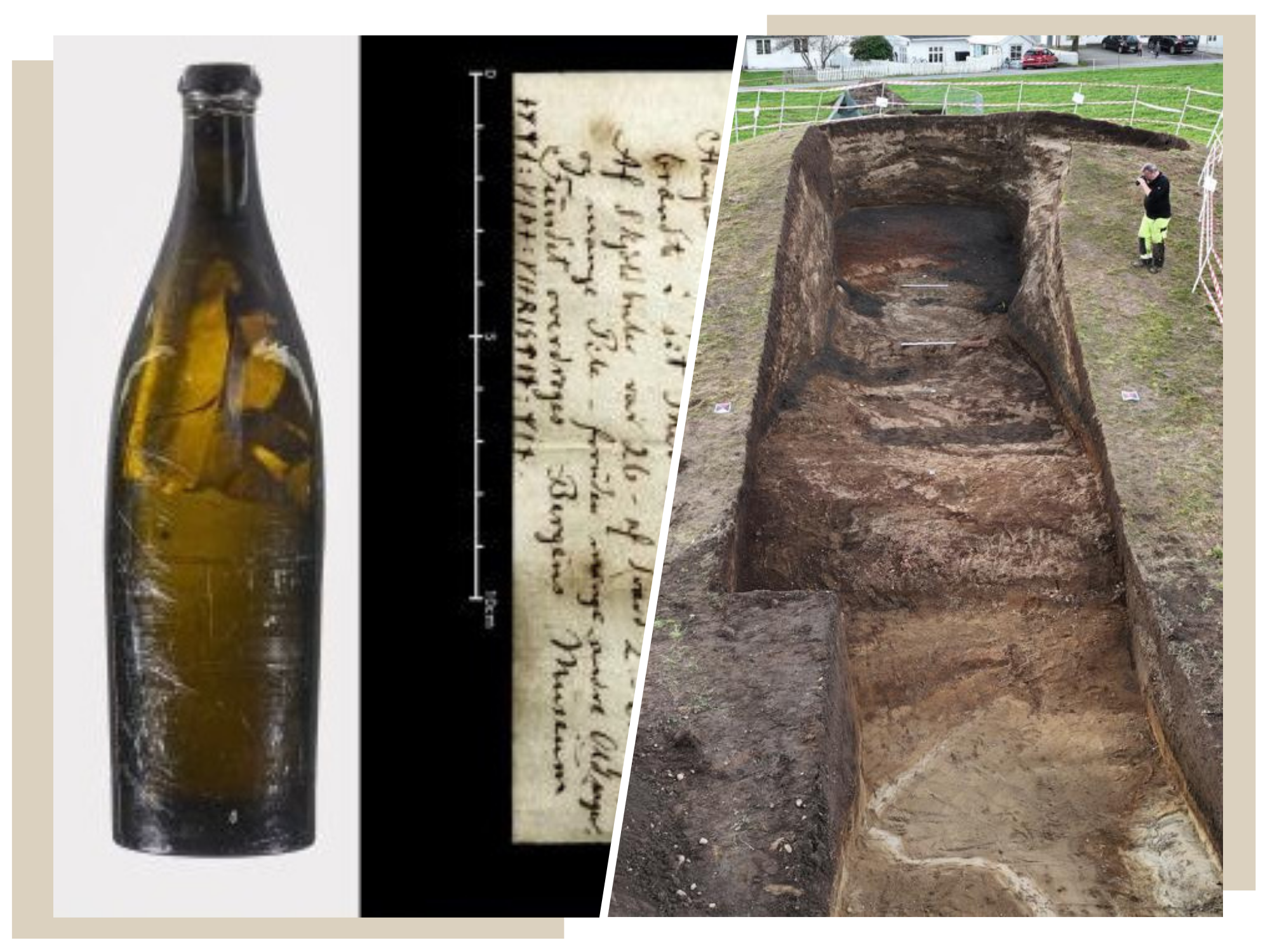

Inside a glass bottle Lorange placed a letter, his business card, and five coins. The letter gives a formal overview of the excavation, offering its date, contents, and purpose. “The mound is built over fallen men. They were buried in their ship with their weapons,” the note read.

At other points in the letter, however, the archaeologist was less accurate. The number of Viking shields Lorange lists is wrong and he fails to mention the ship’s most notably find, an 8th-century bronze vessel that was looted from a church or monastery in Ireland.

The bottle and the letter left behind by Anders Lorange. Photo: University of Bergen.

“It tells us that even though Lorange was the archaeologist from the museum, he was not the one who did the actual excavation work, local farm workers were responsible for that” Morten Ramstad, the project’s lead said in a statement. “He probably didn’t have a complete overview when he put the note in the bottle.”

Another folly arrives at the end of the letter where Lorange left a message in runes, an alphabet used by Germanic before the adoption of the alphabet. Experts in ancient runes were unable to translate the note, Ramstad said, and eventually “we realized that Lorange did not know runes, and had only translated the sentence directly using the younger runic alphabet.” The note they found read: “Emma Gade my girlfriend”—the two would marry in 1877.

It’s the second time archaeologists have discovered a love note from Lorange. During a follow up excavation of Raknehaugen in 1939, researchers found a note dedicated to Ingeborg Heftye, who ended up marrying another man.

These items will be displayed alongside others from the Myklebust dig in an exhibition at the Bergen Museum to celebrate the institution’s 200th anniversary in 2025.