Thousands of years old, ancient rock art can be faint and difficult to see. Now, thanks to the Cotúa Island-Orinoco Reflexive Archaeology Project, some of the world’s best-known petroglyphs have been mapped in unprecedented detail with the assistance of drone technology.

Equipped with photogrammetry cameras, the drones were able to create three-dimensional renderings of the carvings, reports National Geographic. Archaeologists have been studying the carvings in the area for years, but have never before been able to document them with this degree of accuracy.

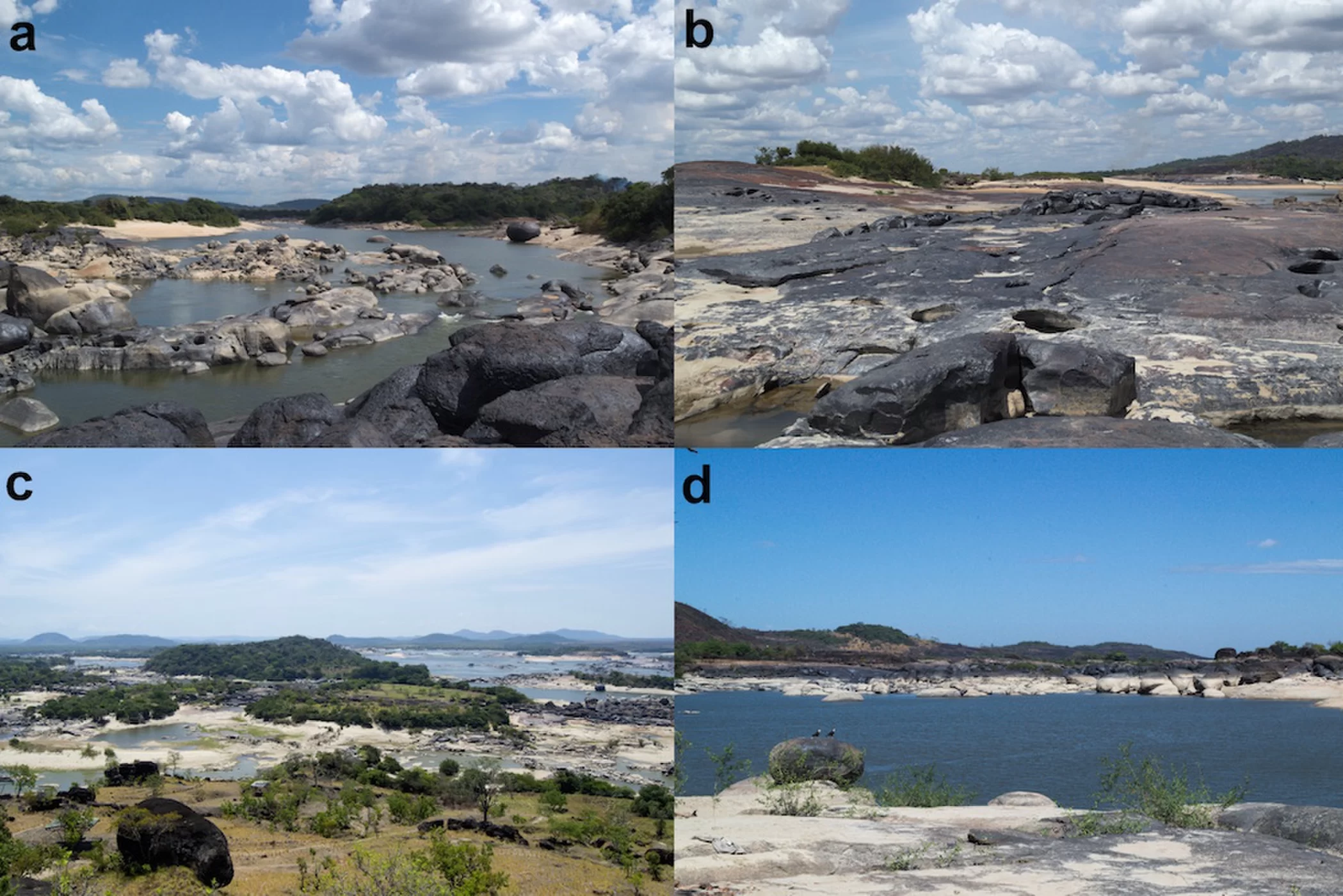

Now in the third year of a planned four-year study, the project has recorded eight groups of 2,000-year-old carved panels from five islands in the Orinoco River’s Atures Rapids, some of which are only visible when water levels fall, in the Amazonas State of Venezuela. These findings were recently published in the journal Antiquity by Philip Riris, a member of the project and a post-doctoral researcher at University College London Institute of Archaeology.

A drone took this photograph of petroglyphs, enhanced with a digital overlay. Photo courtesy of Philip Riris.

The Artures Rapids are well-known among the archaeological community for their massive carvings, such an almost 100-foot-tall snake at the site of Cerro Pintado, discovered centuries ago. Another panel features 93 engravings across 3,200 square feet of rock.

“The size precluded us from doing traditional sketches and tracings of the art itself—it’s simply too big to avoid gross errors in recording,” Riris told Newsweek.

With the high-quality scans of the carvings, Riris and his fellow researchers were able to note similarities between the carvings at the Atures Rapids and those found at other sites in the region, as well as at more distant areas such as Brazil and Colombia.

Aerial photograph of monumental Cerro Pintado petroglyphs with enhanced image overlay. Photo courtesy of Philip Riris.

“The Rapids are an ethnic, linguistic and cultural convergence zone,” said Riris in a statement. “This is one of the first in-depth studies to show the extent and depth of cultural connections to other areas of northern South America in pre-Columbian and colonial times.”

“While painted rock art is mainly associated with remote funerary sites, these engravings are embedded in the everyday—how people lived and traveled in the region, the importance of aquatic resources and the seasonal rhythmic rising and falling of the water,” he added.

Although the project’s work is certain to lead to a better understanding of these ancient drawings, Riris is quick to point out that documenting the carved shapes is only the first step, telling Newsweek that “identifying meaning is far more challenging than recording the rock art.”