Archaeologists in the west of England are on a highly unusual hunt to find the remains of an elephant who once starred in a Victorian-era traveling show known as Bostock & Wombwell’s Menagerie.

The show allegedly arrived near Kingswood, England in 1891, when the local Bristol Mercury identified the ill-fated animal as Nancy, “a fine nine-year-old elephant.” According to a local tale, she died from yew leaf poisoning, and is believed to have been respectfully interred near either Whitefield’s Tabernacle or the Holy Trinity Church.

A team from Wessex Archaeology have been tasked with rediscovering the elephant ahead of a major regeneration of Kingswood planned by the local council. The only historical record they have to work from is hearsay, since there are no written references to either the elephant’s death or burial.

“I first heard about the Kingswood elephant burial in the 1970s when I was doing my rounds as a local milkman,” said Alan Bryant, curator at the local Kingswood Museum. “Since then, I have had countless conversations and debates with local people about it.”

“Searching for Victorian elephant burials isn’t our usual fare,” commented Tom Richardson, a terrestrial geophysicist at Wessex Archaeology, “but a grave of that size would leave a large hole and would certainly be identifiable with the ground-penetrating radar equipment we will be using to survey the site.”

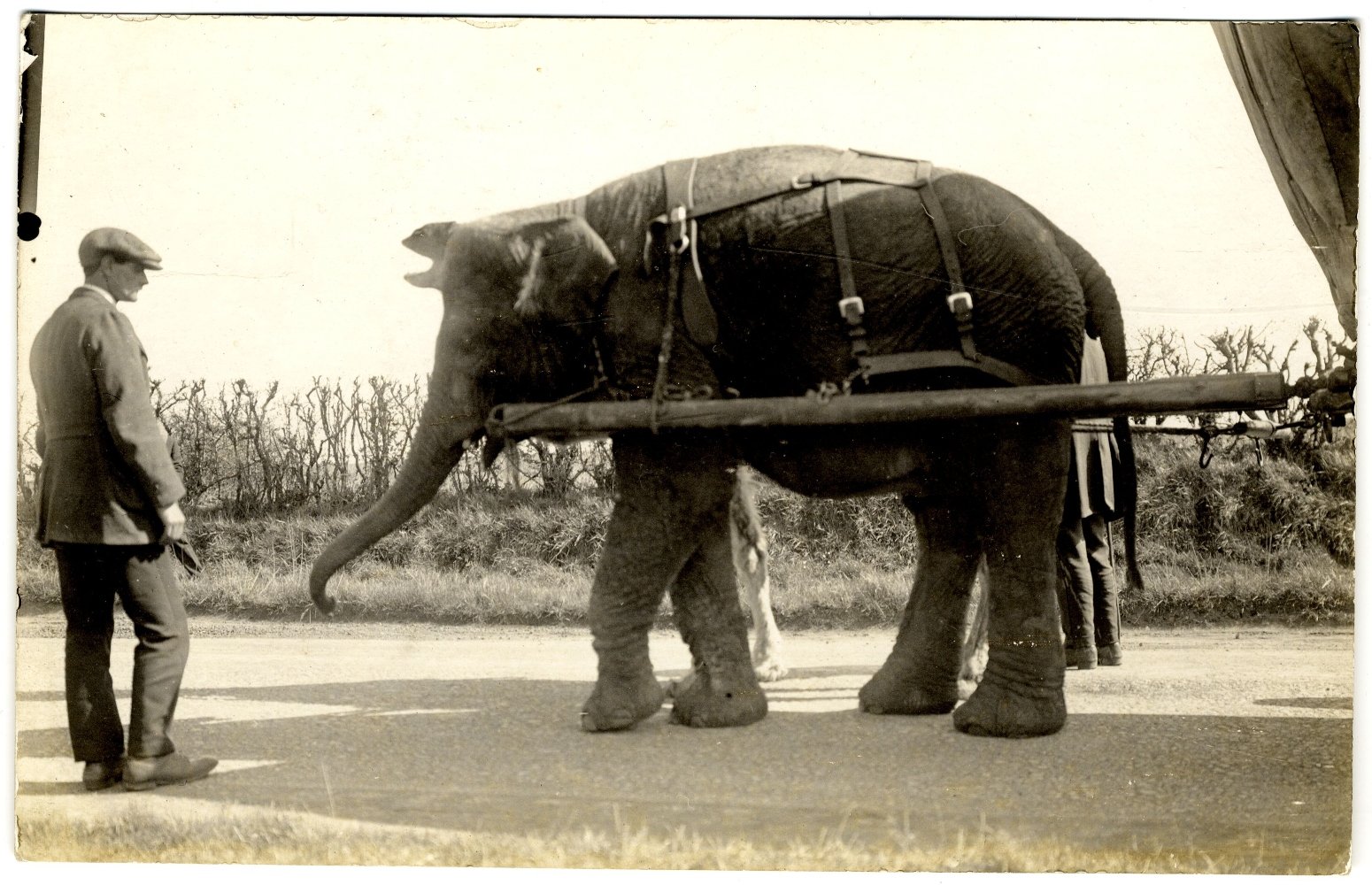

Bostock and Wombwell’s camel and elephant pulling a carriage in 1910. Photo: The National Fairground and Circus Archive/The University of Sheffield.

The import of exotic animals for entertainment was common in the Victoria era and early 20th century, and Bostock & Wombwell’s Menagerie was well known through the U.K. for over 90 years. It functioned somewhat like a traveling zoo and when Nancy came to Kingswood, the Bristol Mercury reported that she was joined by “four camels, 10 or a dozen fine lions and lionesses, three Bengal tigers, a sacred Indian bull, agnu [sic] or horned horse, some leopards, polar and brown bears, a hyena, and a pack of Russian wolves…”

Much like today, Victorian audiences responded particularly well to being awed and surprised, which often meant the animals were trained to perform circus tricks. Its thought that the elephant’s remains, if found, may tell a story about its life spent working in captivity.

“As well as understanding where the animal came from and its age, we may be able to see the impact of its life as an entertainer,” speculated Lorrain Higbee, a zooarchaeologist at Wessex Archaeology. “This may include evidence of confinement including trauma from shackling the animal or arthritis. It may also be possible to detect injuries or strains resulting from its performance duties, such as repetitive movements.”

“The Kingswood regeneration project has presented us with a unique opportunity ahead of the high street pedestrianization work,” said local councillor Chris Willmore. “We’re excited to see what archaeologists may uncover and if we can finally solve this local mystery or find some new mysteries to solve.”

More Trending Stories: