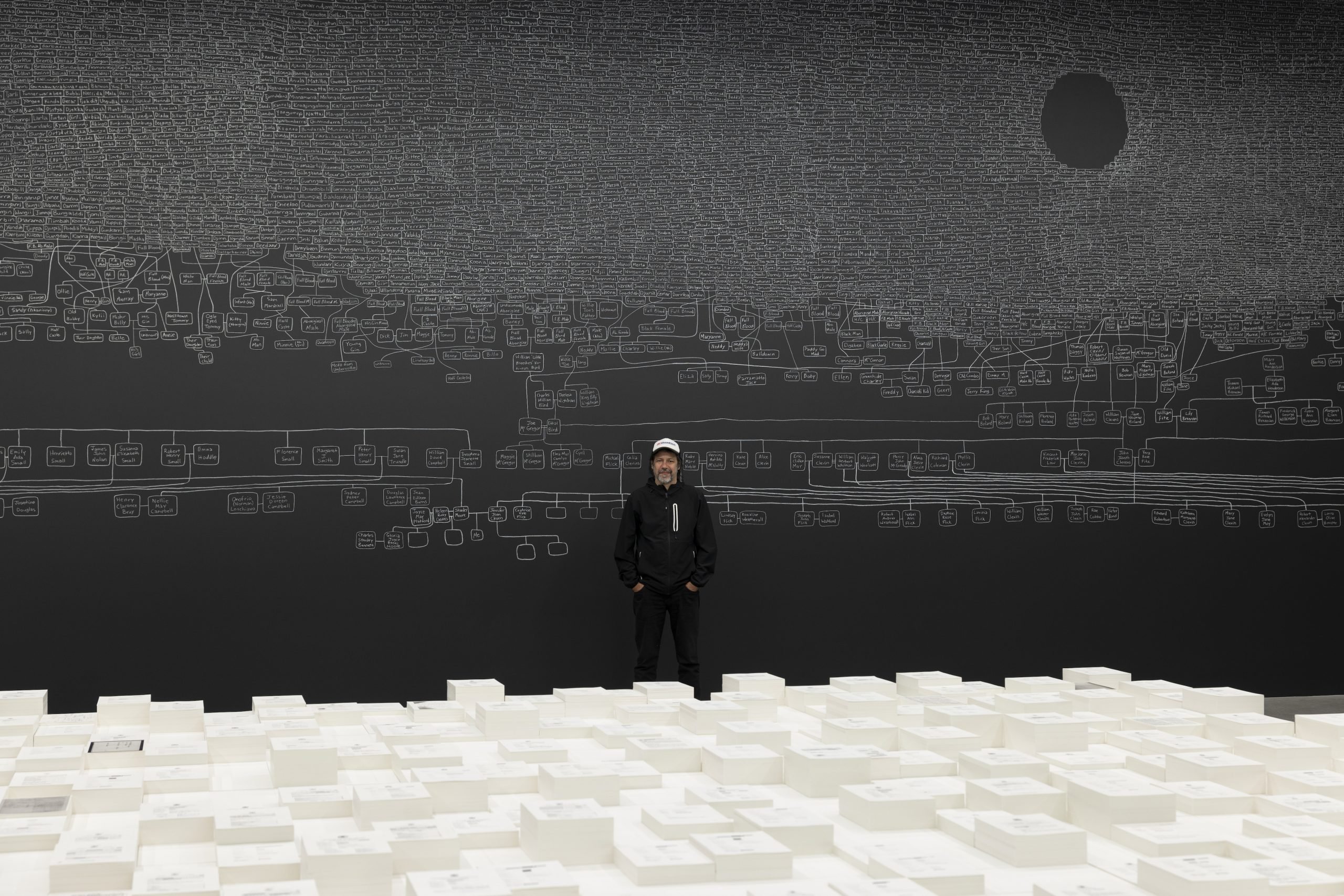

Archie Moore has made history. Not only did he become the first artist from Australia and the first First Nations artist to win the coveted Golden Lion for best national pavilion at the 60th edition of the Venice Biennale this spring, his “quietly powerful” installation “kith and kin” is also a work that dives deep into history, tracing the footsteps of his ancestors dated as far back as 65,000 years in a meticulously hand-drawn family tree inscribed across the surface of the walls and ceilings of the pavilion.

“The recording of names, places and time in the family tree drawing serves as proof of identity — evidence of my Aboriginality,” he said. Born in 1970 in Toowoomba, a city in Queensland, Australia, Moore is a Kamilaroi-Bigambul artist whose practice centers around histories—his own and those of his nation. He explores key signifiers of identity: skin, language, and genealogy, racism, and understanding and misunderstanding that occur between cultures.

The somber work in “kith and kin” is the embodiment of his research that took place over more than four years and included 3,484 people; with piles of state records on display in the center of the installation, Moore draws attention to the depth of research as well as the high rates of incarceration of First Nations people, and its documentation.

We caught up with Moore to learn more about his historical win in Venice, which will sow the seeds for changes to come in the future.

Archie Moore, “kith and kin” (2024), Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti. © the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

As the first Australian and the Kamilaroi-Bigambul artist to win this coveted award, were you surprised when they announced that you were the winner at the auditorium? How did you feel when you were sitting there at the ceremony?

I was very happy to receive the award. While I didn’t know that we were going to win the Golden Lion, we did get a phone call from La Biennale the night before saying that we should attend the ceremony. The call came in just as Naminapu Maymuru-White (who is exhibiting in “Foreigners Everywhere”), her grandson Ŋalakan Wanambi and Merrkiyawuy Ganambarr arrived at “kith and kin” to sing to all of the ancestors that I inscribed into the artwork. It was an incredibly moving experience and I felt touched that they wanted to make this significant gesture within my installation. Naminapu and Ŋalakan gifted me a golden owl artwork, which in retrospect seems like it was a premonition of things to come.

The process of creating “kith and kin” appears to be very intense to outsiders just by the sound of it. It is hard to imagine the incredible amount of research involved (how many pages of documents are we talking about?), and the labor of spending two months inscribing the 65,000 years of history on the dark walls of the pavilion. How was this work developed?

My research started in 2016. I started looking in the archives for my mother’s Kamilaroi-Bigambul side and my father’s British-Scottish side. I have come across hundreds of pages of material in archives and museums and digitized newspapers and archives on the National Library of Australia’s search engine Trove as well. I’ve been using the genealogical website ancestry.com and there are more than 3,500 people in my ancestry.com tree.

I spoke to a lot of people through the Ancestry website, mainly descendants of people who were relatives of people who worked or owned properties around where my parents lived, asking if they had letters, photographs, stories, or rumors that tie back to my family. I also talked to many family members in Inverell and Brisbane.

The recording of names, places, and time in the family tree drawing serves as proof of identity—evidence of my Aboriginality. If anyone were to research those names of my ancestors you will find records that identify them and their tribal groups. This proof of Aboriginality may be required for employment in Indigenous-identified positions, enrolling in schools, government loans and assistance, and for land rights claims where a continuous and unbroken connection to [the] country since colonization needs to be proven. The artwork continues to grow by adding new names, places and other information.

Archie Moore, “kith and kin” (2024), Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti. © the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

How did you pull it off with those months spent in Venice? What were your working hours? What motivated you to keep going and completing the work? How did you share the work with your three collaborators? What was the most challenging part?

I had to draw the mural twice. I did it once at 1:3 scale in Australia in pen and paper on my kitchen table. This was then digitised and placed within a digital model of the pavilion so that we could see the composition of the artwork and tweak the artwork before coming to Venice. And then again in the Australia Pavilion over eight-hour days, six days a week for five weeks. We would draw for 45 minutes and then stretch and rest to ensure our bodies could endure the long installation process. The writing on the ceiling was the most physically challenging and now I know how Michelangelo felt working on the Sistine Chapel.

You have said that your family’s history was something you had “been avoiding.” But this changed when you became interested in genealogy, and you took the opportunity to ask your mother a lot of questions. How and why did you change from avoiding your family’s history to embracing and diving deep into it? What kind of questions did you ask your mother?

My Mother’s minor stroke was what made it urgent—the thought of losing that archive and she also became more open about discussing things. The stroke also seems to have made her more lucid. I was asking her about people I would see mentioned in archival material. I was cross-referencing what she said with what was written down in an official document. This made me aware of how good her memory was.

For instance, I came across a genealogical chart from when anthropologist Norman Tindale visited Boggabilla in 1938 and interviewed my great-grandmother on my maternal side. What Tindale recorded from my great-grandmother seems very accurate and correlates with what my mother has said. He drew a Western linear family tree; in my artwork the linear part of the mural becomes engulfed with and outnumbered by all the traditional Aboriginal names for people, plants, animals, waterways and land.

Archie Moore, “kith and kin” (2024), Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti. © the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

The epic family tree you realized at the pavilion represents 65,000 years of history, and yet, none of this was mentioned in your school days. Has this changed today? And how do you think the visibility and exposure of your Golden Lion win will make a further difference?

I don’t know exactly what is in the school curriculum of today, but I hope there is more of First Nations history being taught compared to when I went to school and was taught that Australia’s history started with Captain Cook and the British invasion. One of the aims of the exhibition was to bring international attention to First Nations Australian culture, sovereignty, and greater recognition of Indigenous deaths in custody and the lack of action in solving this fatal issue. The artwork also highlights how we are all part of one larger family and should be living in peace. Moreover, “kith and kin” foregrounds how injustices, such as racial discrimination and deaths in custody, would not happen if we saw ourselves as part of one large family.

On the Creative Australia website there’s a warning that there may be names or images of First Nations people who are deceased on the website. Is there superstition about this among the Kamilaroi and Bigambul people? Can you share with us some special cultural traditions or characteristics among the Kamilaroi and Bigambul that a lot of people especially foreigners don’t know about?

In most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, hearing recordings, seeing images or the names of deceased persons may cause sadness or distress and, in some cases, offend against strongly held cultural prohibitions.

At the entrance to the “kith and kin” exhibition, there is a warning that the artwork contains names of the deceased. The names of the deceased in the coronial inquests have been redacted out of respect for the dead, even though this is publicly available information so that they aren’t just represented as statistics. While names in the family tree are represented as part of a tightly woven kinship system.

Artist Archie Moore stands on stage with his Golden Lion at the Lion Award Ceremony during the Art Biennale. Photo: Felix Hörhager/picture alliance via Getty Images.

Do you agree that the theme of “Foreigners Everywhere” has finally set a stage for the art world and beyond to properly look at the historical voids of the violence of the colonial era? With many still haunted by the histories of colonization or even facing re-colonization, how will this edition’s Venice Biennale make a difference?

I’ve made an artwork that comes from the personal histories of my family. Accessing documents from archives that feature my great-great-great-grandfather—where my family began to be documented—and everyone else related. Although the accounts of how they were classified, documented, and the nature of their circumstances are personal, they are not unique and other Aboriginal people will have similar experiences. The exhibition covers more than 65,000 years of time; I wanted to show how long Aboriginal cultures have existed and—in spite of invasion, massacres, and systemic over-incarceration —continue to exist into the now.

Did you have time to look at the Biennale or other exhibitions in Venice? Do you have any favorites?

Unfortunately, I did not have time to see all 87 pavilions. The Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise at the Dutch pavilion with their objective of land regeneration through art was one of the highlights.

What will happen to the family tree inscribed on the walls of the pavilion when the exhibition concludes in November?

I chose to use the material of chalk in “kith and kin” because it represents the fragility of life; it is a metaphor for how easily people, histories, and memories can be wiped away. At the end of the exhibition, the walls will be painted over, but those names will forever be part of the pavilion’s DNA. The ancestors and family members will be inscribed onto the walls of the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane, Australia when “kith and kin” is on display in 2025-2026. The installation can be re-made again in other locations.

What is next for you?

My next exhibition expands upon my series of ‘Dwelling’ installations in which viewers are immersed within the architecture and memories of my childhood home. For this exhibition at Samstag Museum of Art [in Adelaide, Australia] there will be a significant moving image component as it is commissioned with the 2024 Adelaide Film Festival.

The 60th Venice Biennale runs through November 24.