What makes a great artist? Divine talent is a good place to start. Next, mix in a strong work ethic, sprinkle on some serendipity, and, for good measure, throw in a handful of useful social connections. For Constantin Brancusi, add hardscrabble determination and a sturdy pair of walking boots.

Of all the artistic luminaries that descended on Paris at the turn of the century, none traveled further and strived harder than the Romanian sculptor.

In 1903, Brancusi set out from Bucharest for the French capital and covered the 1,500-mile-long journey largely on foot. The journey took him well over a year and entailed sleeping outdoors and relying on the generosity of strangers. Brancusi wasn’t carried by some romantic notion of exploring Europe or immersing himself in the natural world; he was simply broke and had no other option.

Brancusi’s journey went by way of Budapest, Vienna, Munich (where he took a break to work as a stone carver), Zurich, Basel, Alsace, and finally Langres, from where he boarded a train thanks to funds wired to him by a friend.

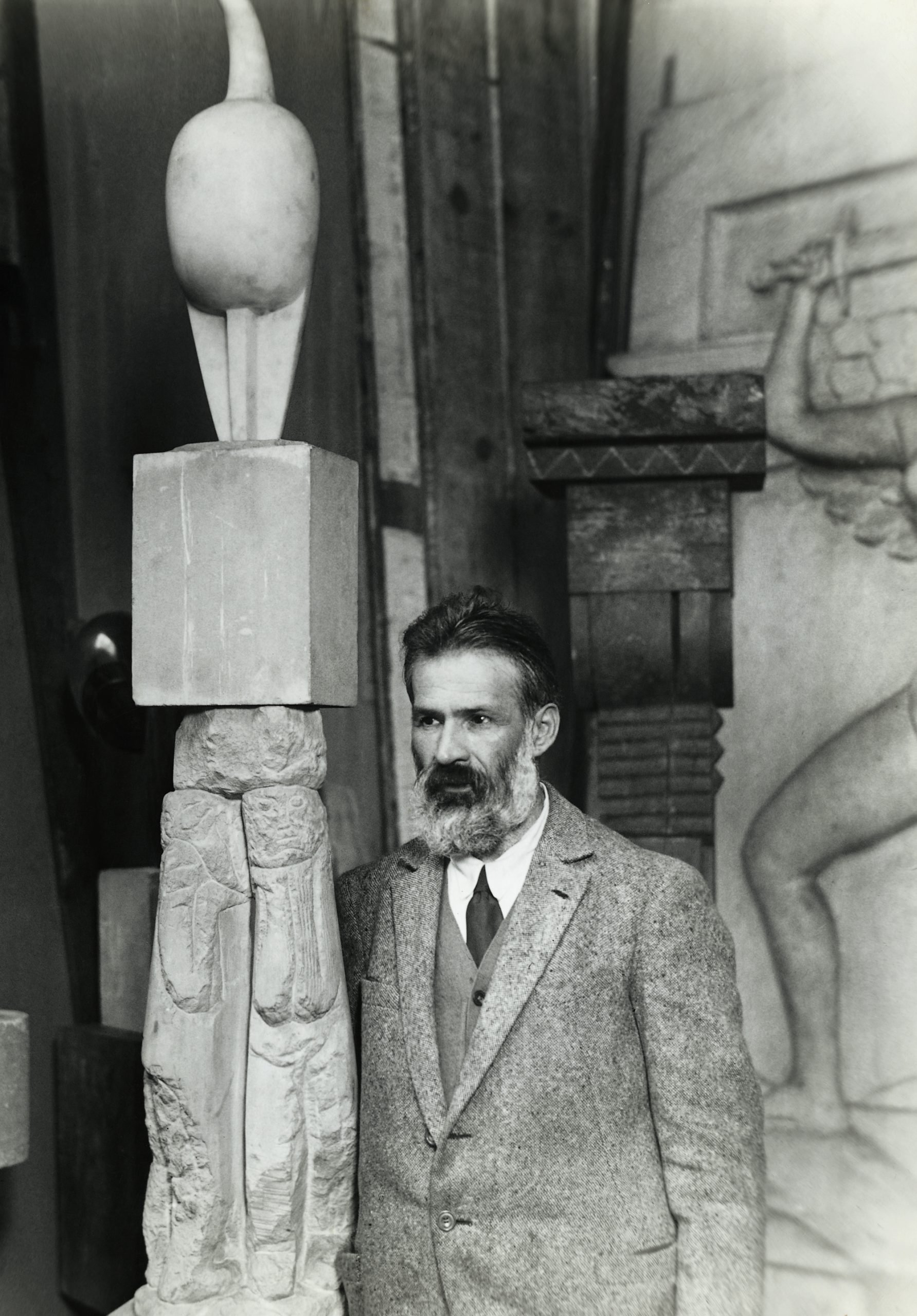

Constantin Brancusi, Endless Column Ensemble (1935–38). Photo: Biris Paul Silviu/Getty Images.

Born in a hamlet in the foothills of the Transylvanian Alps, Brancusi grew up one of seven children in a peasant household. Aggrieved by its oppressive social code and limited opportunities, Brancusi twice tried and failed to run away from home. At age 11, he succeeded, working menial jobs and enrolling in a school in Tirgu Jiu—later the site of Endless Column Ensemble (1935–38), the only public sculptures Brancusi ever made.

From there, Brancusi went first to the Craiova School of Applied Arts and then to the Bucharest Academy of Fine Arts, where he excelled, perfecting the anatomically accurate academic style of sculpture, which he would later abruptly abandon in Paris. His final work from the time is a testament to this style—a bust of Carol Davila, considered a founder of modern medicine in Romania, kitted out in full regalia (Brancusi worked from a death mask).

Constantin Brancusi, Dr. Carol Davila (1903). Photo: Central Military Emergency University Hospital/Bucharest.

Brancusi’s place in Paris may seem preordained, but fresh out of Romanian military service, it was Italy rather than France that called him. When the Madona Dudu Church in Craiova rejected his grant applications, however, Brancusi changed focus and hit the road.

He arrived in Paris at the age of 28 and scrapped his way to success. After a yearlong period of hardship and adjustment, during which time he was prevented from professionally making sculpture, he enrolled in the studio of Antonin Mercie at the École des Beaux-Arts. Brancusi paid his way working as a dishwasher and serving mass at the city’s Romanian orthodox church. Then, his showing at the Salon d’Autumne of 1906 earned him a position as a technician in Auguste Rodin’s studio, which involved turning the master’s compositions from clay into stone.

Rodin was Brancusi’s idol and the era’s undisputed artistic heavyweight. But the younger artist quit after a month, because, as he famously put it, “nothing grows under big trees.” After the unlikely and arduous journey by which Brancusi reached Paris, it should hardly be surprising that once there he continued to forge a path of his own.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.