The name Donald Judd evokes minimalism and Marfa, but those closest to the artist might also hear bellowing bagpipes—his favorite form of music. Leo Villareal remembers house parties Judd hosted around big bonfires and live bagpipe symphonies, despite the artist’s lack of Scottish lineage. While he also loved bluegrass and tolerated the Beatles, the bagpipes resound most notably throughout his art.

Judd first encountered the majesty of bagpipe music in the late 1960s, after he married the Scottish dancer Julie Finch, as an essay published by Judd’s Marfa-based Chinati Foundation explains. Finch took her new husband to hear authentic bagpipe music during a trip to Nova Scotia, and gifted him a Tartan. The couple started collecting bagpipe recordings, and stopped through the New York store Scottish Products while planning a party, where they asked to recommend a solid local piper. Thus, Judd met Joe Brady Sr., who introduced him to the rhythmic, hypnotic ceremonial bagpipe sub-genre of pibroch, which has played across the Scottish Highlands for centuries, particularly to commemorate people and keep pace while rowing.

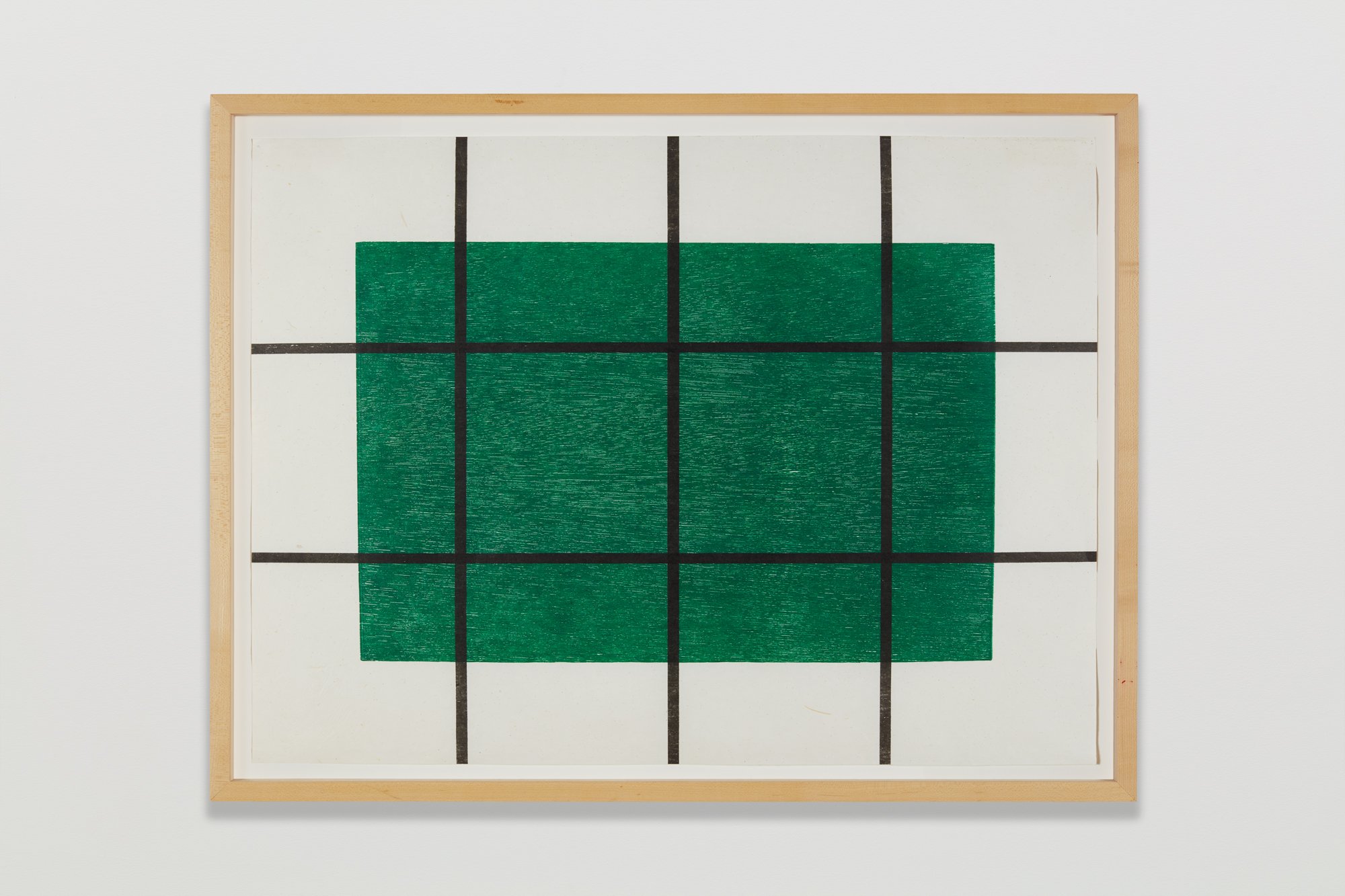

Installation view of Prints: 1992 in Judd’s famous SoHo home. Donald Judd Art © 2020 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image: Timothy Doyon © 2020 Judd Foundation

Joe Brady Jr. started performing gigs for Judd throughout the 1970s, when the young piper was a teen. Meanwhile, the Piobaireachd Society regularly met at Judd’s landmark SoHo home just to trade tunes. “Pibroch is demanding,” Joe Brady Jr. has said. “It’s complicated and melodic. It requires time. Don liked that drone sound in the back and that it was marked by simplified rhythm and pattern. He understood pattern more than other people. It’s a minimalistic type of music—the rhythms are simple, but it’s amazing that you can do so much with just a few notes.”

Bagpipes remained a critical element of Judd’s wider creativity, well after 1978, when he and Finch divorced. Judd kept a scale chart on the kitchen wall of his Marfa home, stocked his library with books about bagpipes, considered forming a bagpipe museum in Marfa, and wore a kilt on occasion, though he never learned to play the instrument. Instead, Joe Brady Jr. continued performing at events and openings around the world.

Installation view of Prints: 1992. Donald Judd Art © 2020 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image: Timothy Doyon © 2020 Judd Foundation

Judd’s artwork echoes pilbroch’s rhythmic drama, from his famed stacks to his sparse geometries of acrylic and sand on board. No other work, though, embodies his inspiration better than the 20 multi-hued woodcut prints he devised with maestro Robert Arber. Their crossing lines evoke both tartan and pibroch, especially when presented as a group. While the suite never reached mass production, 25 editions did get made.

Although Judd passed away thirty years ago, bagpipes remain a massive part of his legacy, featuring in a wide range of Judd-adjacent events such as his posthumous 82nd birthday. Joe Brady Jr. even performed at a dinner in Judd’s former home at 101 Spring Street just last October. The commanding sound of bagpipes fittingly beckoned guests to their seats.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.