Migrant Woman (1936) might be Dorothea Lange’s most iconic work, but her photographs on assignment documenting Japanese American internment during World War II were so powerful that the U.S. government withheld many of her images from publication during the war, spurring suspicions that lasted decades. The commission even shook Lange herself.

“She had gotten so consumed by it and realized the import of it so heartily that it was something that I cannot explain to this day,” said Christina Gardner, who assisted Lange on the job, in an interview that appears in the photographer’s 1994 biography A Visual Life. “I’ve never seen her that way before or since, I never saw somebody that was in such a state.”

Drew Johnson, curator of photography at the Oakland Museum of California, added to this sentiment, “When you consider what she had spent the previous years photographing—which is Dust Bowl refugees, Jim Crow South—the context of that, I think, shows how strongly she was affected by this assignment.”

Newly arrived evacuees line up outside a mess hall at the Tanforan Assembly Center at noon. San Bruno, CA, April 29, 1942. Photo: Dorothea Lange/Interim Archives/Getty Images.

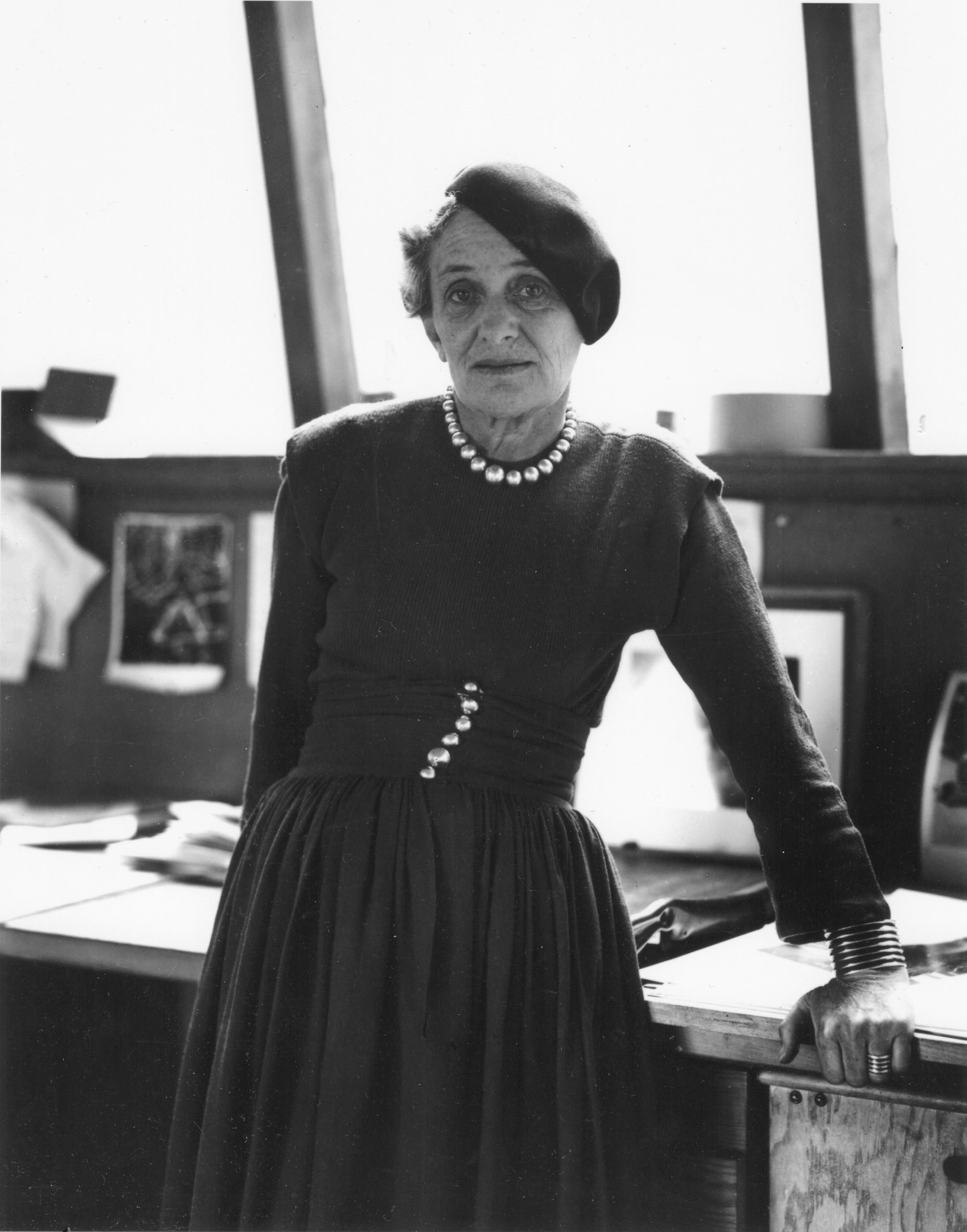

Lange grew up on the Lower East Side from the age five in 1900, after her father left their family. At seven, she contracted polio, which left her with a limp she was always aware of. In 1918, she left New York to travel the world, but became stranded in San Francisco after she was robbed of her life savings, and eventually settled there. She built a career for a decade before documenting the Great Depression and discovering her artistic purpose.

Two months after Pearl Harbor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which gave the U.S. Army permission to “relocate” scores of Japanese Americans to compounds on remote former racetracks and fairgrounds, all ringed with barbed wire. People were given only a few days’ warning to decide what to do with their homes and businesses (which included leaving them in the care of friends and neighbors, or abandoning them), and were transported under military guard, taking only what they could carry.

A US flag flies at the Manzanar War Relocation Center on July 3, 1942. Photo: Dorothea Lange/U.S. War Relocation Authority/Archive Photos/Getty Images.

Within six months, authorities had relocated 122,220 first and second generation Japanese Americans—over 80,000 of whom were American citizens—to “internment camps.” Densho, a nonprofit honoring this painful memory, suggests more accurate terms for the situation, including “concentration camps” or “incarceration camps”.

By then, Lange had married Berkeley professor Paul Taylor, who worked with her for the Resettlement Administration and Farm Security Administration. She earned a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1941, and abandoned it to document the internment process on assignment from the newfound War Relocation Authority the following year.

The Mochida family awaits a bus that will eventually take them to an interment camp, Hayward, California, May 8, 1942. Photo: Dorothea Lange/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images.

Johnson noted that even Lange herself was somewhat surprised she received the assignment. The U.S. government essentially wanted her to cast the internment in a positive light, but Lange’s humanitarian streak drove her “mythologizing energy.”

She captured the situation’s injustice and the dignity of its victims with drama and sympathy, both in the lead up to what the government called “evacuations,” as well as at the camps, particularly Manzanar in eastern California. Guards allegedly stopped her from photographing certain sights. According to sources such as Business Insider, “Lange was not allowed to ‘photograph the wire fences, the watchtowers with searchlights, the armed guards or any sign of resistance.'”

Elevated view of a pair of soldiers stand watch as the luggage of residents of Japanese ancestry is loaded onto a truck prior to the relocation to internment camps, San Francisco, California, April 29, 1942. Photo: Dorothea Lange/PhotoQuest/Getty Images.

What is more, the government “impounded” chunks of her negatives, which wouldn’t be made public until they were quietly deposited in the National Archives after the incarceration camps closed. Conspiracies have since swirled that some images continued to be withheld from the public—even though Lange’s work went on a tour in the 1970s, which contributed to the government dispensing reparations in the following decade.

Rather than a cover-up, Johnson believes the photos’ absence in the 1950s and 1960s most likely stemmed from a desire to forget, shared by Japanese Americans and the country at large. “I’ve never really been convinced that there was an active policy of suppressing them after the war. That was really just a case of people wanting to put the whole episode behind them,” he said. “That included a lot of internees. I’ve met a number of people who were the children of internees, one of them works as a curator at the museum actually… Certainly the larger population in the country wanted to forget about it.”

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.