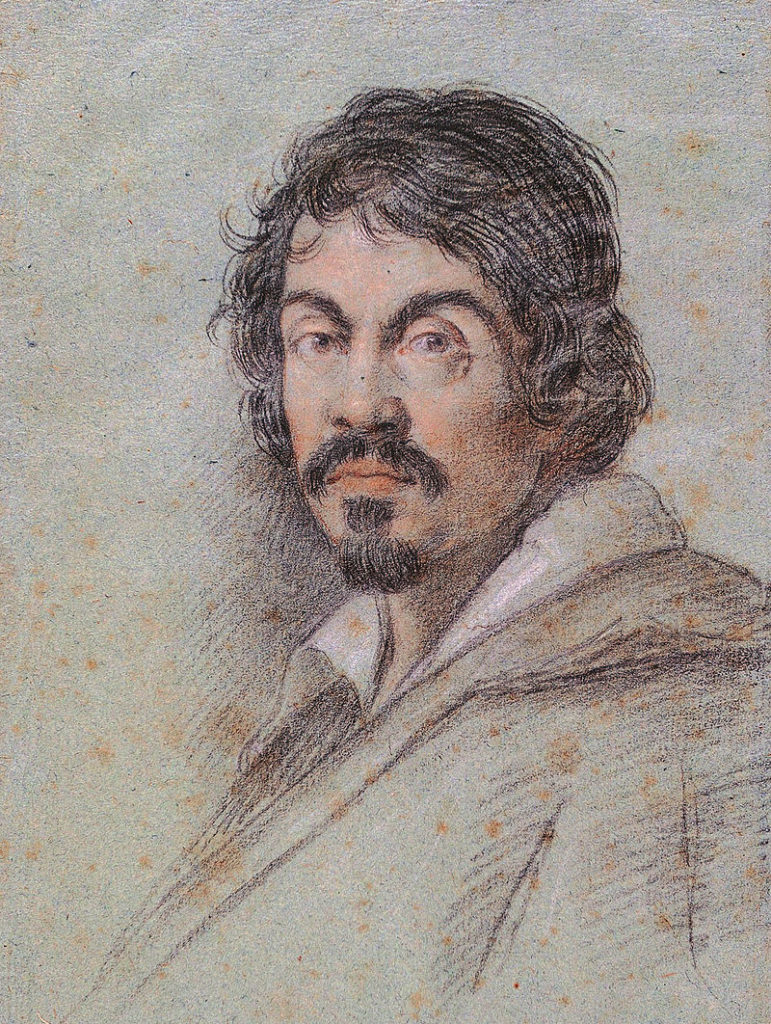

One of the great mysteries of art history is the question of how the great Italian Baroque painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio met his end. An inveterate brawler and troublemaker, even perhaps a murderer, he was the subject of lawsuits and possible revenge plots, and, more recently, a feature film by Derek Jarman and more than one biography. He made his way across Italy, mixing with prostitutes and fighting with gangsters, knights and police alike, and dying at 38 years of age.

The artist grew up in poverty and lost both his father and grandfather to plague on the same day when he was just a child—and his mother when he was only a teenager. As a young man, he fled Milan for Rome after brawling and wounding a police officer. An artist friend introduced him to the world of street fighting.

His paintings of religious scenes won him devoted patrons. He soon began to apply a naturalistic mode to religious paintings, leading to many commissions, often for violent subjects like martyrdoms. He would soon begin to employ a heightened chiaroscuro, or contrast between light and dark, that would gain its own name, for the word for shadows: tenebrism.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps (ca.1594). Collection of Kimbell Museum, Fort Worth.

All the while, the violence continued. One 1604 account said that he would “swagger around” with a sword at his side, ready for a fight, such that it was “most awkward to get along with him.”

The beginning of the end may have come in 1606, when he killed Ranuccio Tomassoni, a member of a wealthy family. Rumors abounded about how it happened and whether it was accidental or intentional. It may have happened in a fight over a tennis-like game, or it may have stemmed from jealousy over Fillide Melandroni, a Roman prostitute who had modeled for Caravaggio several times; Tomassoni was her pimp.

While his patrons had been able to shield him before, this time Caravaggio was sentenced to beheading. An open bounty meant anyone could carry out the sentence. He fled to Naples, and then to Malta, where he was granted a knighthood with the Knights of Malta, a Catholic military order, which presumably would have gotten him off the hook for the murder. But, also in Malta, he attacked a higher-ranking knight, landing him in jail and with the knighthood revoked.

Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes (ca. 1598–99 or 1602). Collection of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica at Palazzo Barberini, Rome

After that, he hightailed it to Sicily, where he continued to paint, but exhibited erratic behavior. He is said to have slept fully armed, and was ambushed by a group of men, possibly in retaliation for the Malta attack, leaving his face badly disfigured.

In hopes that they could secure him a pardon, he sent one or maybe two paintings on the subject of beheading to influential patrons: Salome with the Head of John the Baptist and David with the Head of Goliath. Both featured his own head.

In 1610, apparently encouraged that he would receive one, he set sail for Rome, but on July 28, he was suddenly reported dead. Rumors began to circulate immediately. Did the Tomassoni family have him killed in revenge? Had the Knights of Malta done the same? Many said it was syphilis, resulting from visiting prostitutes. Because he had a fever at his time of death, some said it was malaria, which was rampant, or brucellosis, from eating unpasteurized dairy products.

In the new millennium, with the arrival of advanced technologies, two new explanations have been put forth, and one old one has received new support.

A break in the case came in 2010, when documents emerged indicating that the artist had been buried in Porto Ercole’s San Sebastiano cemetery, in Tuscany. A team of archaeologists and forensic scientists including Italian art researcher Silvano Vinceti went to work, finding one skeleton of a man of the correct height and time of death.

Families with the same surname were located, and DNA tests were about 50 percent compatible with the bones. The researchers said they were 85 percent sure these remains belong to the artist, and that they contained elevated lead levels, so the team concluded that a major contributor to Caravaggio’s death was lead poisoning from the pigments he used in a notoriously messy manner. Some of his increasingly erratic behavior may be explained by the poisoning. But, the researchers admitted, “Lead poisoning won’t kill you on its own.”

Caravaggio, Boy with Basket of Fruit (ca. 1593). Photo: VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images.

Two years later, Vincenzo Pacelli, a professor at the University of Naples, said that his digging in the Vatican’s secret archives and other holdings in Rome revealed a revenge plot by the Knights of Malta. “Caravaggio did not die in Porto Ercole of an illness,” he said. “He was the victim of a violent murder and dumped in the sea near Palo Laziale. His assassination was ordered by the state and blessed by the Holy See.”

In 2018, the plot thickened when a team of experts published a paper in the medical journal The Lancet, asking, “Did Caravaggio die of Staphylococcus aureus sepsis?” He had arrived at Porto Ercole with signs of malignant fever and sepsis, said the paper. They, too, found high levels of lead in the one set of bones that fit the description.

Dental remains, however, revealed just one pathogen: sepsis, which could have resulted from an untreated wound from his last fight. Whoever belonged to this skeleton, they say, died of the infection. (For what it’s worth, Vinceti, too, acknowledged that the subject of his study also had infections and sunstroke.)

Will the lingering mystery ever be solved? Did the great artist die by not one cause but perhaps two: lead poisoning and sepsis? Or was he murdered in revenge for his own violent acts? We may never know for sure, but perhaps future studies will shed further light on this subject of enduring fascination.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.