Louise Bourgeois wasn’t afraid of spiders—she turned them into highly sought after art. But the artist only began sculpting her most iconic forms after many decades. Today, they inhabit top museums and fetch ostentatious sums when they go up for sale. Despite their often looming statures, the true poetic power of these arachnids hails from their creator’s lived experience.

Bourgeois was born in 1911 to parents who ran a tapestry restoration shop around Paris. She grew up helping the family business, and went on to attend France’s most respected academies while working in the studios of her era’s leading artists—which killed her belief in male genius. In 1938, Bourgeois married and moved to New York. Throughout her many years and many mediums, she probed female sexuality and formative experiences, famously calling art “the re-experience of a trauma.” Although peers like André Breton wrote her off due to her gender, Bourgeoise made other friends, including Le Corbusier.

Louise Bourgeois in the studio of her apartment at 142 East 18th Street (ca. 1946). Photo ©the Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Throughout the 1940s, Bourgeois painted domestic scenes and appeared, ambivalently, in an all-women exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery during 1945. Her first charcoal drawing of a spider appeared in 1947. Two years later, Bourgeois’s solo show “Personages” unveiled new totemic wood sculptures blending humanity and architecture atop stilts. “Suspicion grows when you do not trust the ground anymore,” Bourgeois remarked of those works, which were foundational for the sky high sculptures that would followed.

After Bourgeois joined the American Abstract Artists Group in 1954, she evolved from working with wood into marble, plaster, and bronze as means to probe abandonment. In 1982, just before Bourgeois’s MoMA retrospective made her famous, she explained that her oeuvre was autobiographical, inspired largely by her father’s many brazen affairs—especially with her beloved live-in English teacher. Bourgeois admired her mother’s work ethic, patience, and protective streak, but she was also sickly, and passed away when Bourgeois was only 21. The artist was so devastated that she threw herself into a river.

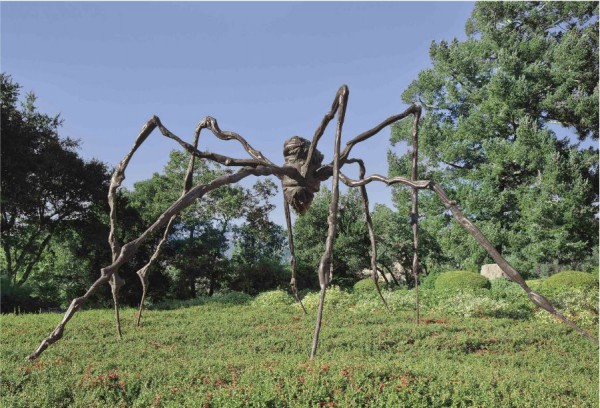

Louise Bourgeois, Maman (1999). Courtesy of Tate.

During her eighties, Bourgeois’s work began contemplating her return to infantile fragility. In the 1990s, the artist fully embraced her intermittent spider motif, sculpting the form at scales ranging from miniatures to the towering renditions now synonymous with her name. In 1996 she created Spider, which has since broken the record for most expensive artwork by a woman three times in a row. In 1999 the Tate Modern commissioned Maman, an even taller spider touting 32 marble eggs. Bourgeois’s larger creatures make viewers feel like kids gazing up at adults. Their graceful if conflicting power and precarity evokes Bourgeois’s unstable upbringing. What is more, the spider’s method of luring its food mimics the traditional female seduction that so fascinated Bourgeois.

“The Spider is an ode to my mother,” Bourgeois said. “Like a spider, my mother was a weaver… Spiders are friendly presences that eat mosquitoes. We know that mosquitoes spread diseases and are therefore unwanted. So, spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother.” Bourgeois was a mother herself, so the works can be said to represent her too. Altogether, these creatures embody the fears Bourgeois discovered as a child, which she continued to probe throughout every stage in her life.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.