What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites bringsyou a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.

Conceptual artist Marcel Broodthaers helped father the art form known as institutional critique as we know it. His 12-year career produced 50 films and 70 solo shows. The traveling Musée d’Art Moderne, which debuted in his Brussels home, is one of last century’s most influential endeavors, paving the way for artists to manipulate the power structures of the museum like a tangible material.

Born in Brussels in 1924, the studious young Broodthaers joined Belgium’s Surréalisme Revolutionnaire and the anti-Nazi resistance. He lived in poverty during his decades as a writer, despite friendships with elites like René Magritte. In 1957, Broodthaers produced his first film—a “visual poem” honoring German Dadaist Kurt Schwitters. In 1962 he befriended Italian artist Piero Manzoni, in town for a show at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, where Broodthaers was a docent. Manzoni signed a certificate of authenticity declaring him a “living sculpture.”

His first-ever sculpture, Pense-Bête (1964), laid Broodthaers’s literary aspirations to rest. The work poignantly encased the the last copies of his final poetry book in plaster—entombing the past and transforming otherwise worthless words into a new, desired object. Broodthaers devoted himself to pinning down the perceived value that art adds to banal items. “I, too, wondered if I could not sell something and succeed in life,” he proclaimed. “The idea of inventing something insincere finally crossed my mind, and I set to work at once.”

Initially he worked with mussel shells and plastic bags, but Broodthaers’s interrogation of the burgeoning art-economic complex culminated in 1968 when he conceived of the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles) after serving as the spokesperson for a student rebellion that had occupied the museum where he once worked.

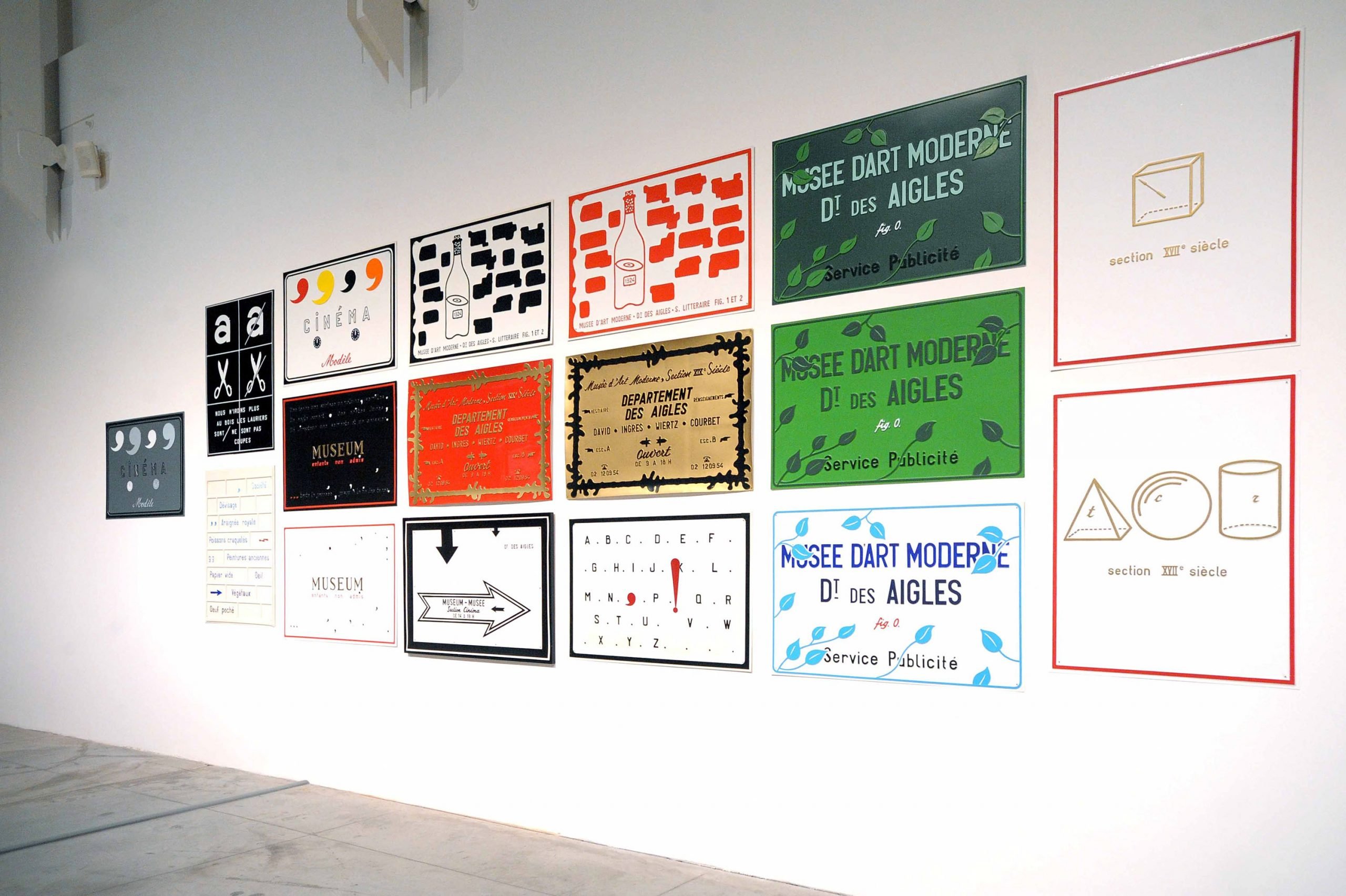

Marcel Broodthaers, Department of Eagles (1968). © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels / Photo: © Erwin De Muer and Cedrik Toselli.

The idea took shape while at home, as Broodthaers arranged milk crates to seat participants for an art world discussion he was hosting. The resulting transient, mock museum grew to 12 sections over its four-year run. Musée d’Art Modern, Département des Aigles debuted on September 27 at Broodthaers’s abode, closing the gap between art and life. He turned rooms into galleries and mounted postcard reproductions of Courbet and Ingres works alongside wall text. He stenciled signs on the windows and sent invitations. German curator Johannes Claedders gave a keynote.

In 1969, Broodthaers traced foundations for “Section Documentaire” in the sand at De Haan Beach. A sign warned the absent public not to touch, but high tide washed it all away. Broodthaers initiated the “Section Financière” in 1971, putting the project up for sale to skirt insolvency. An announcement graced the brochure for that year’s Cologne Art Fair, but no one bit, so he minted gold ingots stamped with eagles and sold them for two times market value, on account of their artistic merit.

The next year, Kunsthalle Dusseldorf invited Broodthaers to present the “Section des Figures,” where 300 pieces of ephemera bearing birds featured placards reading, “This is not an artwork.” Months later, Broodthaers made his first of four Documenta appearances—the only one while he was alive—and concluded the Musée with its “Section Publicité,” a meta-presentation of propaganda around the facsimilie’s nonsense collection.