In 1913, on the last day of the history-making Armory Show exhibition of Modern art at the Art Institute of Chicago, a group of students gathered on the portico to stage a mock trial for one of the exhibition’s most controversial participants, the French painter Henri Matisse.

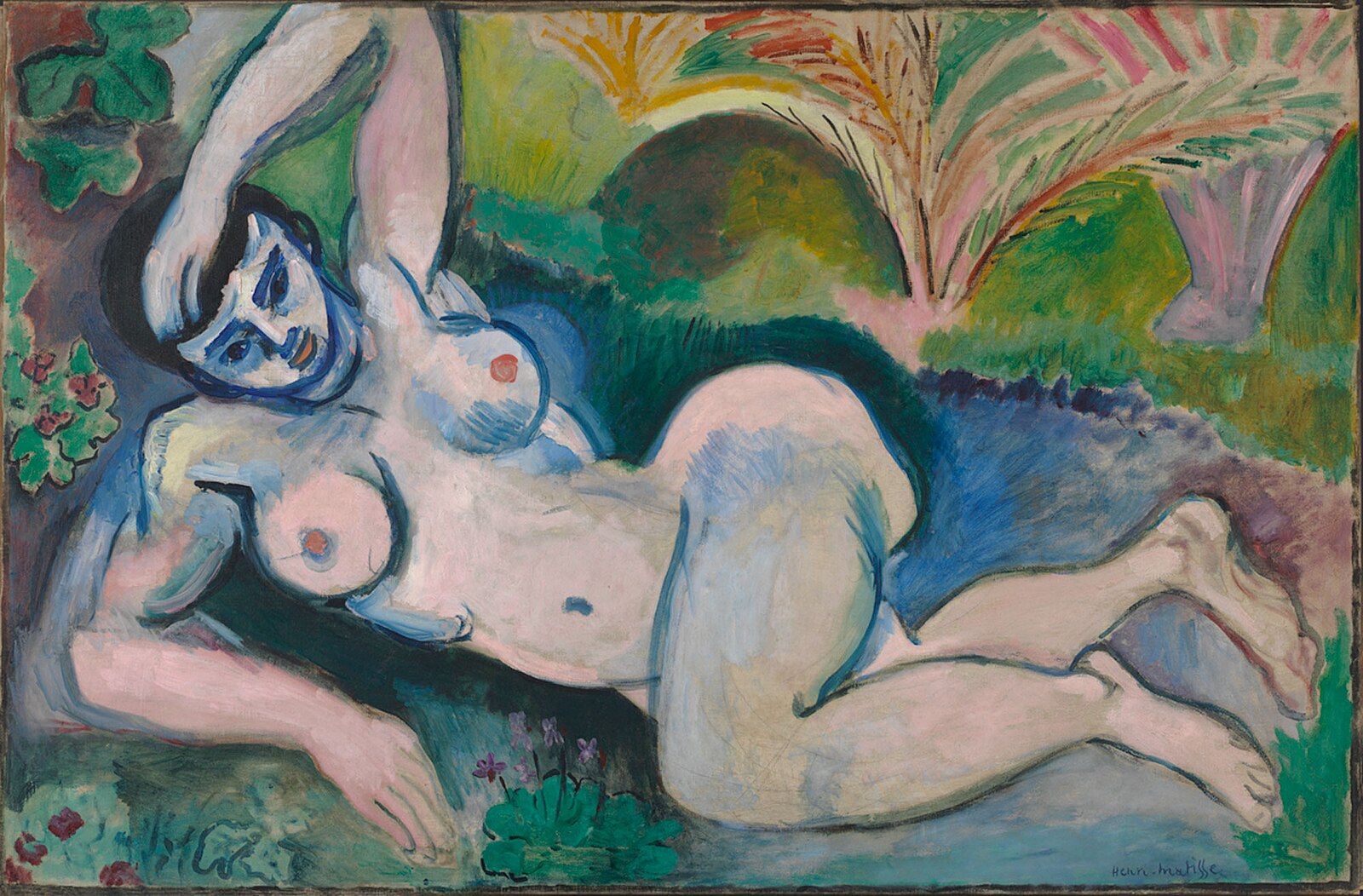

Displeased with the iconoclastic shape and form of Matisse’s Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), a shocking 1907 oil painting after his equally outrageous sculpture Reclining Nude I (1906-07), the students accused “Henry Hair Mattress” of “artistic murder, pictorial arson, artistic rapine, total degeneracy of color, criminal misuse of line, general esthetic aberration, and contumacious abuse of title.”

A student posing as the artist was placed in shackles as a jury condemned him to death. “We regret that you have only one life to give for your principles,” another student, playing the role of chaplain, announced before his execution. “So let it be with all artistic traitors. You were a living example of death in life; you were ignorant and corrupt, an insect that annoyed us, and it is best for you and best for us that you have died.”

Henri Matisse in his studio in Cannes. Behind him is his work, Decorative Figure (1925). Photo: Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images.

At this the defendant dropped dead and the students cheered. They then prepared to burn reproductions of Matisse’s work, including Le Luxe II (1907), Goldfish and Sculpture (1912), and, of course, Blue Nude, though some local news reports from the time claim they were stopped by Art Institute authorities before they could set their effigies ablaze.

The mock trial took some of the exhibition’s organizers by surprise. Newton H. Carpenter, the traditionally minded secretary of the Art Institute, had not expected such a negative response. On the contrary, he had feared that the modern art on display would corrupt his students and lure them away from their classical training, just as it had at schools in Europe.

The Art Institute of Chicago in the 1920s. Photo: Getty Images.

Others had braced themselves. The Armory Show had already whipped up a storm when it debuted in New York City earlier in the year, and for good reason. Up until that point, exhibitions in the U.S. had exclusively shown the work of the old masters and, sometimes, the contemporary artists that imitated them. Matisse could not have been further removed from Michelangelo.

Responses to the mock trial were mixed. In general, the students enjoyed the support of their teachers. Aside from Carpenter, who was actually criticized for allowing the Armory Show to open in the first place, the Art Institute faculty was, in the words of artist Walt Kuhn, “almost a solid unit against our exhibition and insisted upon escorting their classes through the various halls and in ‘explaining’ and denouncing every part of the show.”

Others criticized the students as narrow-minded and unwilling to accept unstoppable changes sweeping the art world. A writer for the Chicago Evening Post referred to the mob as “hating even beyond the point of violence.” Walter Pach, a member of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors who helped Kuhn organize the Armory Show, was also critical, but felt that Matisse and other forward-thinking artists would ultimately have the last laugh.

“10 or 20 years from now,” Pach said, “some of these students will be eating crow if they are as truthful as their instructor Charles Francis Browne, who has been partaking of that dish ever since he derided the impressionist painters when he was a student at Paris.”

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.