Claude Monet, the founder of Impressionism, revolutionized 19th-century art with his bold use of pure, vibrant colors and his focus on capturing light and scenes of modern life. Unlike traditional artists, the Impressionists were pioneers of en plein air painting, taking their easels outdoors to capture landscapes in real-time. The term “Impressionism” itself began with a critic.

Writer Louis Leroy decried Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) as just an “impression,” not a finished work. But the artist and his circle, including Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas, embraced the term. Rejected by the art establishment, they organized independent exhibitions that redefined modern art.

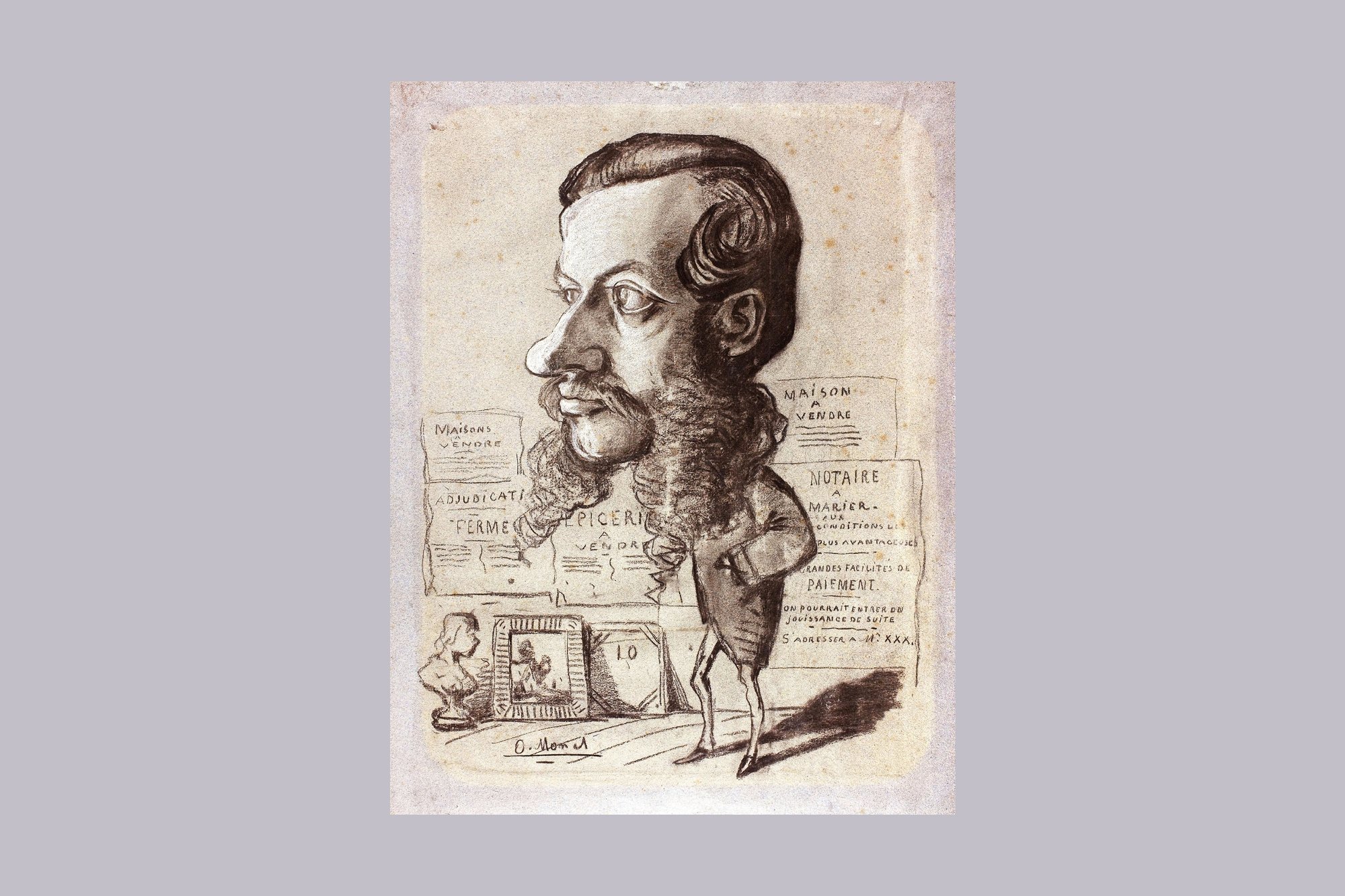

Before he emerged as an Impressionist painter, Monet was “O. Monet” a local caricaturist in the town of Le Havre in the Normandy region of northern France. He created witty drawings of locals, with exaggerated features that highlighted their quirks and personalities. All were signed with his birth name, Oscar-Claude. By the age of 15, Monet had already made a name for himself, selling these humorous drawings to locals in the town.

Claude Monet, Caricature of Jules Didier (Butterfly Man), (ca. 1858) Charcoal, heightened with white chalk, with smudging, on blue laid paper (discolored to light brown), 616 × 436 mm. Photo by: Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

This early work may seem worlds apart from his later Impressionist masterpieces, but his observational skills were already well trained. Monet’s caricatures showcased his keen eye for detail and personality, skills that he later brought to his landscapes. In the early 1860s, he met Eugène Boudin, a painter who encouraged him to move away from his satirical style. Monet later credited Boudin as “the first to teach me to see and to understand.”

Working alongside Boudin outdoors, he became captivated by the natural world’s colors, light, and movement. Impression, Sunrise (1872) is set in Le Havre and portrays a misty harbor with ships in the dock. The muted tones of blues and grays evoke the harbor’s hazy, subdued atmosphere, while the bright orange sun stands out vividly, contrasting against the softer hues and drawing focus to the early morning sunrise.

After moving to Paris, Monet met other avant-garde artists, including Gustave Courbet and the Barbizon School painters, who encouraged him to pursue a realist and naturalist approach to painting. Monet soon adopted a new philosophy: an artist should capture fleeting personal impressions rather than fixed details. This inspired him to develop his signature loose brushwork and luminous color palette. “I wanted to grasp something that was impossible,” he would later say, articulating his ambition to paint the intangible qualities of light, air, and weather.

Claude Monet, Impression, sunrise (Impression, Soleil Levant), (1872). Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images; Paris, Musée Marmottan.

For anyone interested in Monet’s later works, the Courtauld Gallery in London has just opened “Monet and London: Views of the Thames,” running through 19 January 2025. This exhibition presents his dreamlike, atmospheric London scenes, which he painted between 1899 and 1901, featuring the Thames shrouded in mysterious light and fog, with Charing Cross Bridge, Waterloo Bridge, and the Houses of Parliament as central subjects.

Monet had long wished to show this series in London, where many of the works were painted, but this never happened at the time. Now, this show brings his vision to life, exhibiting the works just 300 meters from the Savoy Hotel, where he stayed while painting them.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.