Not being the sporty type may hamstring your Olympic dreams today, but they needn’t have crushed them before 1948. For 38 years beginning in 1912, gold, silver, and bronze medals were up for grabs in Olympic art competitions across five categories: architecture, literature, music, painting, and sculpture. This set of awards was named the “Pentathlon of the Muses,” its winners decided by an international jury.

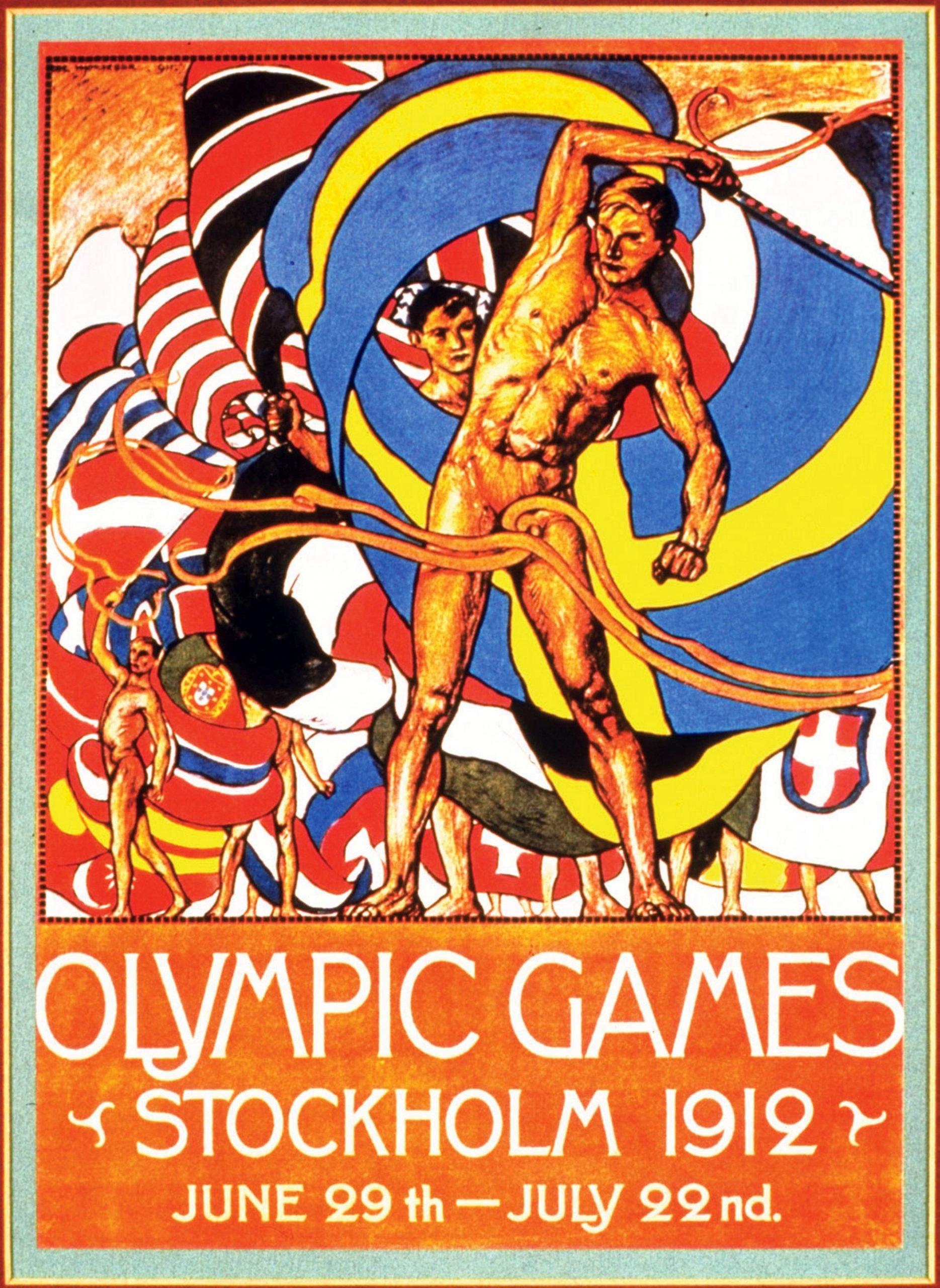

The ancient Olympic Games had been run every four years between 776 B.C.E. and 393 C.E., but were stopped the Roman Empire’s Christian emperor Theodosius I banned all “pagan” festivals. In 1896, Pierre de Coubertin, created the modern Olympic Games on the idea that they could offer an opportunity to celebrate excellence in both body and mind. He first proposed adding art competitions in 1906; it took six years before the events were inaugurated at the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm.

Pierre de Coubertin (at center in bowler hat), with British Royal Edward, Prince of Wales, and French athlete Justinien de Clary on a field at the 1924 Games in Paris, France, 1924. Photo: Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Though the rules at the art contests would evolve over the years, their core principles held. All entries were required to be original and sport-inspired. Artists could also submit multiple works, meaning they could chalk up more than one win in a competition. The Olympics’ traditional gold, silver, and bronze awards were given out in each category, though not always.

While the Swedish organizing body objected to the creative competitions, they went ahead in 1912. A mere 35 artists submitted works, though. And save for the sculpture category—where sportsman and sculptor Walter Winans took gold for An American Trotter, his carving of a harness racer—only gold medals were awarded in competitions for painting, graphic arts, and music. (De Coubertin himself landed the top prize in literature after submitting his poem, “Ode to Sport,” under two pseudonyms.)

Over the years, new subcategories emerged, including “dramatic”, “epic,” and “lyric” categories for literature, and “paintings”, “prints,” and “watercolors” for fine art. Architecture also became a category from 1928.

Jean Jacoby, Hurdle Race (1936). Photo: ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that the art competitions began to be taken seriously. The number of submitted artworks grew from 193 works in 1924 to a whopping 1,100 at the 1928 games in Amsterdam. In 1932, at the Los Angeles Olympic games, over 384,000 visitors travelled to the Museum of History, Science, and Art to view the submitted artworks, despite a reported dip in participation in the games that year.

Sadly, the art competitions ceased after 1948 because of International Olympic Committee (IOC) rules concerning the professional status of participants. All Olympians were required to be amateurs, but the IOC were consistently finding that almost all competitors submitting artworks were professional artists. Some had even been allowed to sell their works at the end of the 1928 Olympic exhibition in Amsterdam.

When last art competitions wrapped in 1948, Germany, then France and Italy, led the nations that had clinched the most medals for their creative submissions. While there have been efforts to reboot art events at the Olympics, none have successfully come through.

Jack B. Yeats, The Liffey Swim (1923). Photo: © National Gallery of Ireland.

Across more than three decades, several high-profile artists (certifiably not amateurs) have participated in the Olympics. Luxembourg artist Jean Jacoby clinched two gold awards for his painting triptych Étude de Sport (1924) and his drawing Rugby (1928); while Irish painter Jack B. Yeats scored silver for his Impressionist canvas, The Liffey Swim (1923), and British artist Jon Copley also took home silver in the 1948 graphic arts category.

Two competitors made history during the first 42 years of the modern Olympic games by winning medals in both sports and arts competitions: Winans, who apart from triumphing in the first Olympics art contest, was a double gold-medal marksman, and Hungarian gold-medal swimmer Alfréd Hajós who earned a silver medal in town planning design in 1924. (Winans donated his historic sculpture to the Swedish Museum of Athletics; The Liffey Swim is in the National Gallery of Ireland)

Alfréd Hajós, Olympic Swimming and Architecture Medalist

While artists may no longer participate in the Olympics, art remains very much a part of the games. Per the Olympic Charter, host countries are required to “organize a program of cultural events” while the Olympic Village is open. This year, in the run-up to the forthcoming competition in Paris, its committee commissioned Marjane Satrapi to create massive tapestries inspired by this year’s events, while Alison Saar has been tapped for a public sculpture to be installed in the capital, as part of the IOC’s ongoing Olympic Art Visions initiative.

No official prizes for any of these participating artists, but, hey, they’re all winners to begin with.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.