What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.

Pablo Picasso could do no wrong for most of his career, but, boy, did he try. In 2001, British historian, physicist, and author Arthur I. Miller added to Picasso’s existing rap sheet with his book Einstein, Picasso: Space, Time, and the Beauty That Causes Havoc. Drawing on the spirit of Leonard Shlain’s Art and Physics (1991), Miller’s tome maps parallels between Einstein and Picasso’s disparate if complementary innovations, which reshaped notions of time and space.

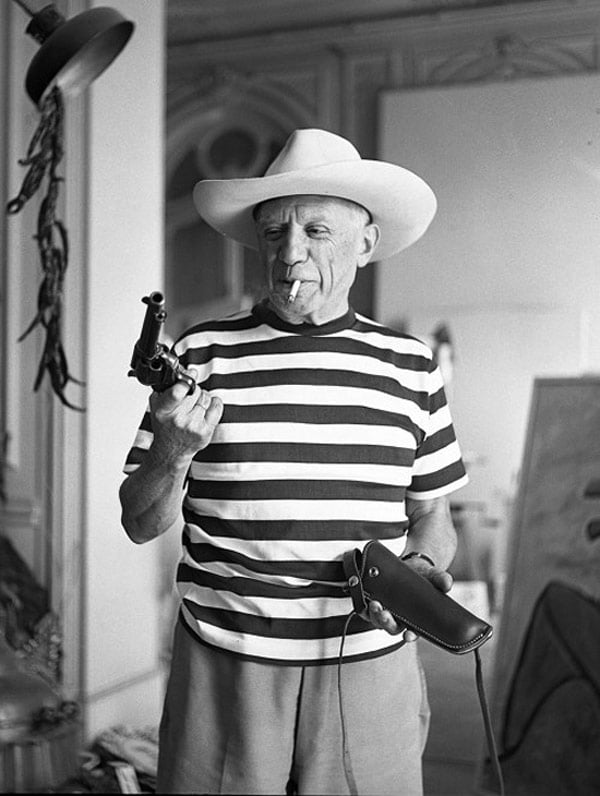

On page 31, Miller mentions that Picasso carried a Browning revolver loaded with blanks. “He would fire at admirers inquiring about the meaning of his paintings, his theory of aesthetics, or anyone daring to insult Cézanne’s memory,” Miller wrote.

Legend has it that the gun once belonged to playwright Alfred Jarry—patron saint of the Absurdists, and the creator behind the parody science of pataphysics. Picasso adored Jarry. A 2020 exhibition around Jarry’s legacy at The Morgan Museum & Library noted that Guillame Apollinaire and Max Jacob spread rumors about the interactions between Picasso and Jarry, Without doubt, Picasso drew Jarry many times, and claimed his pet owls descended from the playwright’s birds.

A drawing of Alfred Jarry. Photo: Bettmann / Contributor.

“Playwright Alfred Jarry normally carried a pistol on him,” Miller explained. “During a dinner party, Jarry accused the sculptor Manolo of not being drunk enough and took a shot at him. In the ensuing confusion, Jarry dropped his pistol and ran. Apollinaire, who was there, lent the pistol to a ‘friend’—as he recalled in a memoir of 1909… The ‘friend’ was almost certainly Picasso.” Later on, actor Gary Cooper would give Picasso the gun shown in André Villers’s famous 1959 photo of the painter.

Picasso must have first acquired Jarry’s gun in the five years between Apollinaire’s memoir and 1904, when he initially met the writer. “Like Jarry, Picasso used his Browning as a pataphysical weapon, in a sense playing Père Ubu au natural, disposing of bourgeois boors, morons and philistines,” Miller said.

Pére Ubu is the “gluttonous, greedy, and cruel” antagonist at the center of Jarry’s early, incendiary play Ubu Roi (1896). Miller’s account conflicts with the artist’s demonstrated understanding that Ubu wasn’t worth admiration. The Morgan‘s show noted: “The painter used Ubu as a symbol for injustice and oppression during the political upheavals of the 1930s.”

At any rate, Picasso had entered his morally gray era by the time he got Jarry’s gun. He hit a career stride in 1901, during his Blue period, which grew into his Rose period—and the start of Cubism. In 1904, Gertrude Stein met and made her first purchases from Picasso, marking a major milestone in his career and ending his monetary woes. Picasso’s acclaim further skyrocketed when he debuted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907. The Guardian recounted that Picasso mocked an unwitting Henri Rosseau with a lavish party in 1908, and when the Mona Lisa was stolen three years later, Picasso and Apollinaire were major suspects. History’s most prolific artist was a flawed man of contradictions. He shot blanks, but even those are dangerous at close range.