The Art Loss Register (ALR), which claims to operate “the world’s largest database of stolen art,” according to its website, might not be such a reliable resource.

The Art Newspaper recently released a jaw-dropping report on the erratic and questionable research methodology employed by the company.

The issue at hand is that ALR has issued title certificates for certain works that have turned out to have been stolen or looted, which has resulted in its implication in several high-profile international art disputes. The most recent of these involves Picasso stepdaughter Catherine Hutin Blay—who is missing artworks she entrusted to storage and which appear to have turned up in the collection of Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev via an executive of the Swiss Le Freeport company, Olivier Thomas, who was arrested last month.

According to TAN, ALR “has been implicated in the alleged fraud unraveling around Yves Bouvier,” who founded Le Freeport. A lawyer for Bouvier told one of the paper’s Paris correspondents that his client “asked for certificates from the ALR for all the paintings he bought, demonstrating that they had not been registered as ‘missing or stolen.'”

James Ratcliffe, ALR’s general counsel and director of recoveries, tells TAN that the ALR “has no record of requests for certificates directly from Bouvier…Searches were submitted over two years ago from a corporate entity based in Switzerland for pictures which match the descriptions of the Picasso works that are now reported to have been stolen. Certificates were issued because the pictures were not in our database.” Ratcliffe then confirmed that ALR is now liasing closely with French police on the matter.

In a phone interview with artnet News, Ratcliffe confirmed that certificates had been issued but added, “It’s somewhat unfair to say that we issue certificates for works that were subject to a claim. They were searched with us in 2013, and they were reported stolen to the police in 2015.”

Ratcliffe continues, “We do actually have a system in place to protect things. We offer positive registrations for people and they can add things to our database to register it as something that they own. Then if it comes up in the market for sale, we can then go to the person and say, you do realize this is coming up at auction…”

Therein lies the heart of the problem. ALR’s “due diligence” appears to involve a cursory search of their database before they certify the first owner—or art thief—brings a painting to their doorstep. Ratcliffe admits that information offered about the provenance of a work must be “taken on trust”.

Others see ALR’s often exorbitant finders fees as problematic as detailed in a chapter in a forthcoming book, The Art of the Con by Anthony Amore, head of security and chief investigator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. In a chapter called “The Captor,” Amore outlines how a Massachusetts collector, who had a valuable Cezanne painting stolen in 1978 and recovered more than two decades later, was forced to sell it in order to pay ALR’s $2.6 million fee, which was based on the fair market value of the painting.

Could the collector “have circumvented all of the intrigue by going straight to the FBI when the paintings had first surfaced in 1999?” Amore continues, “The case might have ended much sooner—and at far lesser cost.”

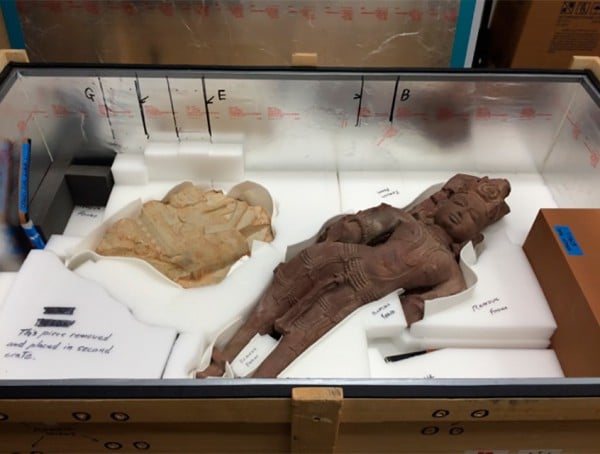

This Ganesha statue purchased by the Toledo Museum of Art from Subhash Kapoor in 2006 was looted, and will be returned to India.

Photo: the Toledo Museum of Art.

The other cases mentioned in the report include works by disgraced art dealer Subhash Kapoor, who is awaiting trial in India on charges of trafficking thousands of stolen works. Kapoor obtained ALR certificates clearing some looted works before he sold them to international museums, including the National Gallery of Australia and the Honolulu Museum. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is also involved with Kapoor; it requested an ALR search into the provenance of objects it acquired from the dealer.” We reached to the LACMA press department to ask whether the museum had rethought this decision in light of the report, but the museum has not yet responded to messages seeking comment.

This past April, artnet News also received documents about a civil action against Kapoor brought by New York district attorney Cyrus Vance. From in or about 1995 through in or about January 2012, Kapoor committed various felony crimes through his gallery, Art of the Past, including criminal possession of stolen property in the first degree, according to the papers. The DA’s office provided artnet News with a detailed list of $107 million worth of Kapoor’s antiquities that are “forfeitable.”

Ratcliffe told TAN: “In some cases the provenance provided to us by Mr. Kapoor was false… Our certificates make clear that not all thefts are reported to us, and a search with the Art Loss Register cannot excuse the undertaking of further due diligence if such an exercise is appropriate.”

El Greco Portrait of a Man (1570) was returned in March to the heirs of Nazi victim Julius Priester.

The most convoluted of the cases involves a Nazi looted El Greco for which—unbelievably—the ALR had twice issued clear title certificates despite extensive efforts by the heirs of the victim Julius Priester to reclaim the work over the years. The painting, Portrait of Gentleman (1570), was finally returned to Priester’s heirs this past March after the Commission for Looted Art in Europe (CLAE) saw the work on a New York art dealer’s website and filed a claim. London based Art Recovery International helped negotiate the settlement.

Prior to that, Priester had made extensive efforts to track down the work before his death in 1955, and his heirs later took up the cause.

ALR initially said its “first record contact” with Priester’s heirs was in 2005 about the collection as a whole. Later ALR revised its statement, telling TAN, “We have now tracked down some earlier correspondence… going back to 2001.”

Ratcliffe told the newspaper that assurances made at the time of the 2012 certificate were “taken on trust” and not investigated further since there was no “red flag” raised.