Don Draper’s Art Collection

What if Don Draper were an art collector?

More specifically, what if the “Mad Men” creative genius had started buying Abstract Expressionist art from some of the swankier galleries in New York City in 1962? Given the dizzying art boom of the last generation, how would he have fared?

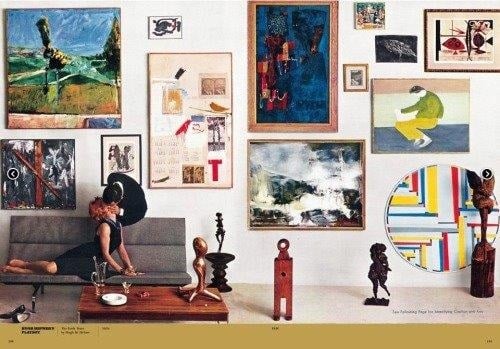

The answer is to be found in Playboy magazine, of all places. In 1962, the editors of the men’s magazine offered readers a tutorial on the topic: “The Fine Art of Acquiring Fine Art.” They “purchased” more than two dozen works, most ranging in price from $150 (a tiny abstract painting by John Grillo) to $6,500 (Landscape with Smoke by California painting star Richard Diebenkorn), for a total of $137,000. An untitled 1950 Jackson Pollock, at $40,000, and a Willem de Kooning, $20,000, represented the lion’s share of the spending spree.

Late last year, Taschen books, publisher of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy: 1953–1979, the six-volume history of Playboy magazine, asked Amy Cappellazo, a private dealer who for years served as a chairman of Christie’s International, how much the collection would be worth today. The answer: $120 million.

Which is something like a Coney Island studio apartment turning into the Hyannis Port Kennedy family compound, appreciation-wise, over two generations. Not everything soared, by any means, of course. So, what separated the “winners,” in price and fame, from the “losers?” Talent, perhaps, but also the dealer’s hawking the works.

Playboy, apparently very well-advised back then, bought works by Leo Castelli’s entire stable of artists—which included Johns and Robert Rauschenberg—and bought selectively from Andre Emmerich and Sidney Janis, three dealers who were to define the market in 20th century art. Interestingly, Castelli Gallery, now blue chip, was only about five years old at the time, so Don Draper would’ve been quite cutting-edge in his shopping.

Conversely, the artworks bought through dealers in Chicago, like a Richard Hunt sculpture or a Harry Bouras, or through less well-connected dealers elsewhere, apparently didn’t do as well. A Reuben Nakian sculpture that sold for $1,000 50 years ago goes for “only” 10 times’ that today. Nakian was showing at this time with Egan Gallery, after falling out with the most powerful Edith Halpert. Galleries which have long since closed tended to have the artists who have been forgotten.

Other lessons to be drawn (tongue firmly in cheek, as we’re not reading too much into such a small sample):

— Buy young. The younger artists fared the best of all, with a work by the then 32-year-old Jasper Johns zooming to $15 million today from $2,800 in 1962.

— Go for one-of-a-kind. In pure rate of return, drawings and multiples fared less well than unique works. Interestingly, those were the same findings of the British Rail Pension Trust auctions of the early 1990s, one of the larger institutional “bets” on art ever taken.

— Don’t expect to be able to resell everything. A 1960 Bouras that could be had for $350 is now $20,000, notes the article in Taschen magazine with the current values. But where, exactly? In the case of several of the artists whose works were purchased back in 1962, there isn’t a resale market for them today—so much so that they were omitted from the updated valuation.

— Don’t buy through interior decorators and don’t buy without seeing the art in person. That was Playboy‘s advice in 1962, and it stood the test of time.

Interestingly, it turns out Hugh Hefner took Playboy‘s advice, buying De Kooning’s Duck Pond for about $20,000 himself. At its last appearance at auction, in 1997, Duck Pond sold for $530,500, Cappellazzo notes. Hef’s looking pretty smart, isn’t he? Except that if he had held on to it, it would likely bring eight figures today.

Or, more interestingly, he’d own the De Kooning.

Warring Piano Projects in Milan

Renzo Piano, architectural darling of the art world, may be a little less busy next summer. The construction of his sweeping and keenly awaited €4 billion project in Sesto San Giovanni, the largest architectural project in all of Europe, is likely to be delayed by construction and traffic related to the nearby Milan Expo. That city’s giant world’s fair opened May 1. Its organizers are anticipating 20—24 million guests.

The Expo is designed in part by Jacques Herzog and will feature national pavilions by architects Norman Foster, Daniel Libeskind, and Piano himself, says Piero Galli, a director general of the fair. The two Piano projects will “run parallel” with each other, he says, and the Expo won’t slow the masterplan for Sesto, which creates a 173-acre park and retrofits the industrial plants and offices of huge steel producer Falck S.p.A. into libraries, schools, etc. But an Italian tour manager familiar with the region says the Expo timetable will likely back-burner the Piano construction located just a few miles away. Bizzi & Partners Development, owner of the Sesto, could not be reached for comment.

The Expo has already caused some upheaval in the art world calendar, prompting a one-time move of the Venice Biennale a month earlier. (Previews began May 6.) Of some comfort to art-worlders however, the Expo has a “foodie” theme, will feature an exhibition on the history of food in art, and special events will include, says director of tourism Alessandro Mancini, a special breakfast in front of The Last Supper. (Yes, that Last Supper.)

Kudos

In advance of the intriguing exhibition opening May 22 at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art in Charleston, SC, “The Insistent Image: Recurrent Motifs in the Art of Shepard Fairey and Jasper Johns,” Interview Magazine talked to Fairey about the music that influences him, about Johns and Rauschenberg—and the shocking change he’d make in his Barack Obama “Hope” poster if he were to make it today.

Art World Report Card appears every Thursday. The author can be reached at apeers@artnet.com and writes on the art world on Twitter @LoisLaneNY.