The Trial of (Avedon’s) The Chicago Seven, or What’s Wrong with This Picture?

A lawsuit heads to the Supreme Court of the State of New York on March 31st that’s an art world cautionary tale of fine print, leaky storage, and the inexact science of assigning value, particularly to photographs. Far from a contained spat, the dispute has touched the Gagosian Gallery and threatens to besmirch some reputations elsewhere. It has captured the attention of art world players frantically seeking a clue to how suits related to damaged art—like the many pending ones that arose out of Hurricane Sandy—will be treated by New York courts.

In Richard Avedon Foundation vs. AXA Art Insurance Corporation, the Avedon foundation is suing AXA over a damaged life-size photograph of the famous Vietnam War protestors—Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin among them. Here’s what happened: On or about December 8th, 2011, a panel of the Avedon triptych The Chicago Seven, September 25, 1969 was lain on a table for retouching, this in advance of a planned 2012 exhibition at Gagosian) at an art storage facility. Water from a leaky pipe dripped on it.

The Foundation, which has its collection insured by AXA for $87 million, brought in a conservator and an appraiser. She issued a lengthy report concluding that the artwork, one of an edition of three, had virtually no commercial value due to obvious undulations and tide marks on the bottom half of one panel—the legs of two of the “seven.” The value of the damaged print was estimated at $50,000, just 2 percent of what the appraiser considered its market value pre-damage: $2.5 million.

AXA called in its own appraiser, who valued it lower pre-damage, and gave the price quote, after accident and restoration, at about $1.6 million. He used various formulas that involve, among other measures, the percentage of the canvas damaged. A key dispute between the valuations is that the Foundation’s takes into account sales of Avedon’s at Gagosian for $2–3 million that took place after this piece was damaged. (Gagosian exhibited one of the other Chicago Seven in his acclaimed 2012 Avedon show; the third is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

With two warring valuations in place, the sniping began.

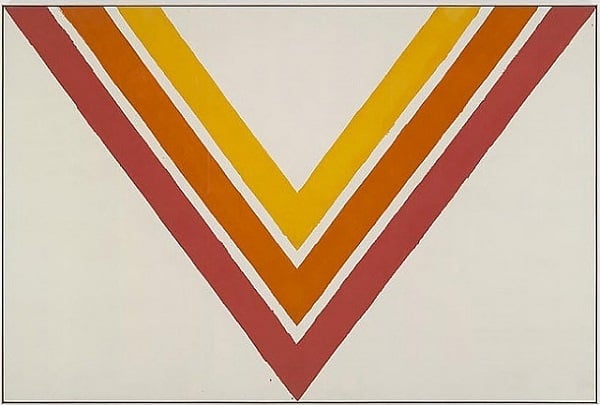

Richard Avedon, “The Chicago Seven, September 25th, 1969.”

Papers from AXA’s side charge conflicts of interest, wonky math, and “gratuitous . . . self-defeating” behavior on the part of the Foundation. In the event of a huge discrepancy between appraisers, the Foundation’s policy with AXA specifically calls for an umpire, a third appraiser, to be called in. It is this provision, common in many art insurance policies, that the judge will consider.

AXA says its appraiser’s relatively brief report does not constitute a formal appraisal, so the judge has no occasion yet to force an umpire. The company declined to comment for this case, as did the Foundation’s attorney.

But there are a lot of things funny about this case. The Avedon Foundation maintains that the photo retained only 2 percent of its value—but that’s a strangely convenient number. If it had been completely destroyed, the Foundation would, under terms of its policy with AXA, have to surrender it to the insurer.

Meanwhile, the fact that the insurer hasn’t yet had an official appraisal of the damage done so long after the incident is just curious. As for methodology, valuing a work by the percentage that was ruined may be a common method of estimating damage but . . . well, how would that work with the Mona Lisa?

The suit matters.

In an interview, Victor Wiener, who was called in by Lloyd’s of London to consult when Steve Wynn famously put his elbow into a Picasso, said that determining the value of art in the case of damage is such an inexact science—“people are looking for something that could provide precedence.”

Jasper’s 50 Shades of Gray

The museum industry is not known to be fleet-footed, but “Jasper Johns: Regrets” is a show that was raced into MoMA before new works by the artist could disappear into private collections. At 83, the legendary painter still had a few new moves left, at least according to the co-curators of the exhibition, who saw works that had already been sold at the artist’s Connecticut studio last year and interceded swiftly.

“We wanted to share our great surprise” at the art, said Ann Temkin, MoMA’s chief curator of painting and sculpture. For Johns, “it’s a new direction that we we’re not expecting,” said Christophe Cherix, the museum’s chief curator of drawings and prints.

The show is riddled with more art history footnotes than a Janson’s: In June 2012, in a Christie’s auction catalogue, Johns spotted a photograph of the artist Lucian Freud, head in hands. Francis Bacon had used the photograph of his friend Freud for his own works. There was a tear in the photo, leaving an odd shaped hole. This void, doubled and folded on itself as a mirror image, appears in the center of each of the MoMA works, mostly drawings but including one gorgeous all-gray painting.

And what about the title? What does Johns regret, exactly? “It’s a tease, it’s provocative, very deliberately,” says Temkin. “The title is pregnant with meaning.” It ostensibly refers to a rubber stamp Johns uses to decline the many invitations and interview requests he receives, she notes. Or does it?

After the Ab-Ex

More people have debated whether Kenneth Noland was a Color Field painter or a Minimalist than have fought over the gum-or-candy identity of Razzles. One thing’s for certain: After the visual chaos of Armory Arts fair week, his spare works of circles, stripes, and chevrons will come as a palate cleanser. Pace Gallery, its 32 East 57th Street iteration, opens a show of his post-1975 work Friday March 21st that runs through April 19th.

Alexandra Peers is on Twitter @LoisLaneNY.