While Dadaism did give rise to Surrealism, the artistic movement hardly invented absurdity. In fact, a short-lived phenomenon called Les Arts Incohérents was spawned in the late 19th century in Paris, its antic-laden art predating Dada by about 30 years.

Founded by writer and publisher Jules Lévy, the loose collective’s numerous exhibitions and balls introduced the public to a new kind of art wrought with text, unconventional materials, and negative space. All of it was defined by sardonic humor, wielded to better unpack the foibles of art, politics, and society.

Below, we revisit the movement that evolved from cabaret culture to leave an indelibly bold mark on art.

Why did Jules Lévy form the Incoherents?

Les Arts Incoherents catalogue cover illustration by Jules Cheret. Photo: Swim Ink 2, LLC/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images.

Lévy was a journalist and Montmartre cabaret fixture. He was in the Hydropathses literary club, alongside the playwright Alfred Jarry and Alphonse Allais, a comic writer who later became the only real star of the Incoherents.

As a man of the media, Lévy was embedded in the zeitgeist and had a knack for promotion. In the wake of the Paris Salon’s demise when the French government withdrew its sponsorship in 1881, he conceived of his own salon, based in his apartment, at which his friends and peers could gather to mastermind inventive, often brazen, subversions of art traditions.

Lévy named his project Les Arts incohérents, riffing off the term les arts décoratifs, which, to his group, represented a tired heritage. “Death to clichés,” he decided, “to us young people!”

What were some of the group’s activities?

Jules Foloppe, aka Gieffe, La tortue et les deux canards, d’apres Lafontaine (1884), on view at “Les Arts Incoherents” in Paris, 2021. (Photo: Stephane de Sakutin / AFP via Getty Images.

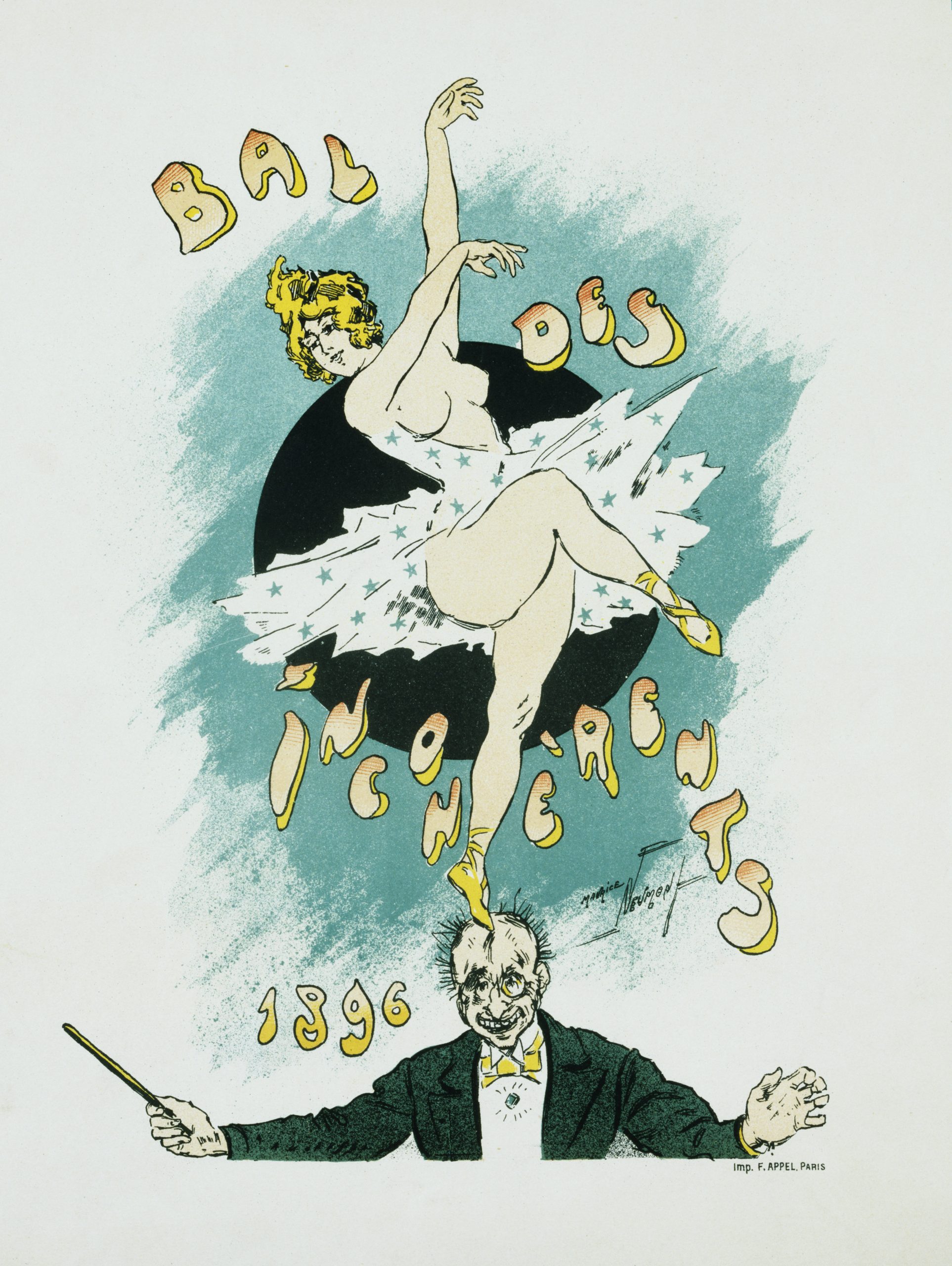

Between 1882 and 1893, the Incoherents staged seven showcases in Paris, as well as a few satellite events, including one in Nantes in 1887. Many of the group’s shows were also huge parties, where masked revelers relished in visual art by people who couldn’t paint or draw, texts by painters, and other acts of satirical irreverence.

Surviving relics from these events include brightly painted posters with imagery such as a man being swallowed by a moon; artworks such as Marc Sonal’s etching of a woman without a face; and Lévy’s own caricatures, which were included in illustrated catalogs that accompanied each ticketed event.

Arthur Sapeck, The Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe (1887). Photo: public domain.

But perhaps the most lasting image to emerge from the movement was by Arthur Sapeck (the pseudonym of Eugène Bataille), who produced a black-and-white collage of Mona Lisa smoking a pipe. Sapeck created the image, coincidentally and remarkably, the same year Marcel Duchamp was born.

Sounds like a blast. How were the Incoherents received?

Despite the ostensibly low-key nature of these salons, the Incoherents captured the attention of the press and public. A whopping 2,000 people attended the first showcase at Lévy’s apartment, including stars like Édouard Manet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. At the group’s height, an Incoherents happening was the social highlight of the season, eagerly reported on by the media. Unfortunately, that same fame machine that helped elevate Lévy’s movement would bring him back down all the same.

What happened to the collective?

Cover of Le Courrier Francais with a caricature of Jules Lévy by Adolphe Willette, with the caption “The aftermath of Incoherence – Jules Lévy gone mad!” (1886). Photo: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

In 1884, the Parisian paper Le Courier française started mockingly calling Lévy “the official unofficial Incoherent.” Undeterred by the increasingly hostile press, he launched a publishing house in 1886 to promote his own friends and projects—a move interpreted by some as Lévy using the movement for his own personal benefit.

Incoherents events continued through 1893, but Lévy’s last salon went by unnoticed. He watched new movements advance, while his own fell into relative obscurity. Many of the jokes made across the group’s published editions were so dry and niche that they barely made viewers giggle.

Lévy would continue, unsuccessfully, to restart the Incoherents through 1896. But by then, the joke had worn thin: “All that is outdated, outmoded,” went a review in the French Mail. “Inconsistency joined [by] decadence, decay, and other jokes.”

Why are we still talking about the Incoherents?

In beckoning radical humor into the bounds of fine art, the Incoherents paved the way for movements including Surrealism, conceptual art, and even Constructivism. Bataille’s subversion of Mona Lisa, too, was surely a touchstone for Dadaists.

For more than a century, there has been sparse attention paid to the Incoherents—save for a 1992 showcase at the Musée d’Orsay—and its memory mostly lived on mostly in secondary sources.

A showcase of Les Arts Incohérents pieces recently discovered on view in Paris, 2021, including the green cab curtain by Alphonse Allais on the right. Photo: Stephane de Sakutin / AFP via Getty Images.

That is, until 2021, when a mysterious trunk of Incoherent works surprisingly surfaced. Initially thought to be a box “of little interest,” it contained documents, drawings, and other objects wrapped in rags. In it were 17 artworks including a green cab curtain by Allais, a roll of antique fabric that has a pretty solid claim as one of the earliest readymades; Jules Foloppe’s surreal paintings on wood; and an all-black canvas by Paul Bilhaud, its back affixed with a label that reads “Arts incohérents – 4, rue Antoine-Dubois, 4, PARIS.”

The unearthing of the trove has sparked new scholarship on the group. And in a move that might either be to the credit or consternation to the original Incoherents, the French government has deemed the newly discovered works national treasures.

For as long as there has been art, revolutionary movements have continually reshaped its creation and perception. Artcore unpacks the trends that have shaken uptoday’s and yesterday’s art world—fromthe elegance of 18th-century Neoclassicism tothe bold provocations of the 1990s Young British Artists.