Last weekend, the Orange County Museum of Art opened its long-awaited new home, a $94 million building 14 years in the making, with the return of the California Biennial. Missing from the festivities was artist Ben Sakoguchi, who has said that the institution rescinded his invitation to participate in the show due to swastika imagery in his painting.

The censorship controversy, which Sakoguchi explained in detail on his website, threatens to cast a pall over what Surface magazine previously called “a nice feel-good story and moment of triumph for Orange County.”

A native of San Bernardino who now lives in Pasadena, the 84-year-old artist, who as a child was imprisoned with his family at a Japanese internment camp in Arizona, was among 20 local artists selected to appear in “California Biennial 2022: Pacific Gold.”

Four days before the exhibition’s October 8 opening, he shared on his website a detailed timeline of the events leading up to his ultimate exclusion from the show.

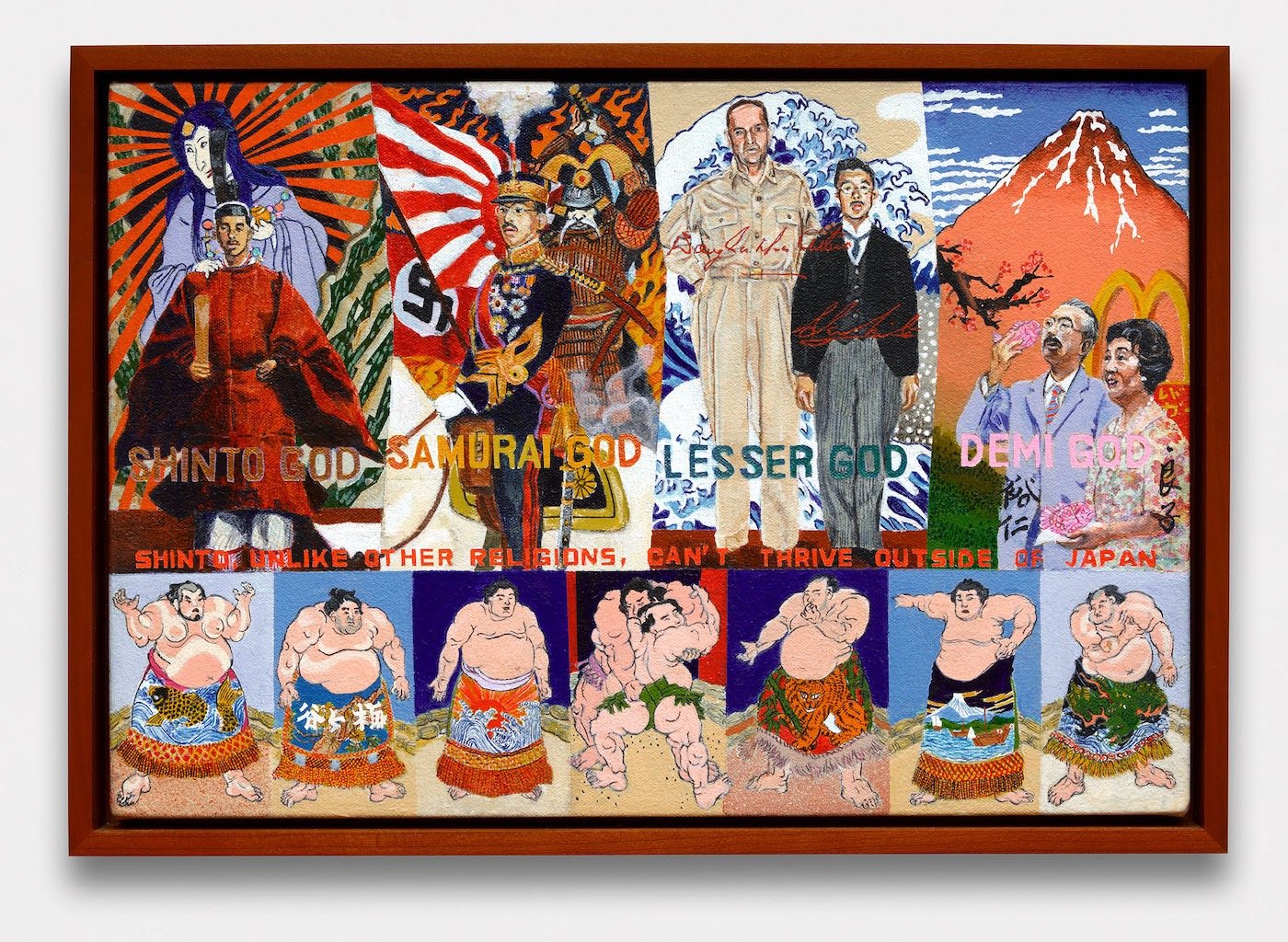

Ben Sakoguchi, Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Curators Elizabeth Armstrong, Gilbert Vicario, and Essence Harden extended the invitation to him in January. On June 24, they told Sakoguchi that they specifically wanted to show his Comparative Religion 101, a massive, 16-panel painting packed with references to different world religions. It was to be the artist’s first time showing the work.

The central panel shows the tiny figure of Albert Einstein overlooking the Grand Canyon, based on a real photograph of the scientist. Surrounding the scenic view are depictions of giant Buddhas, depictions of God in the style of everyone from Michelangelo to Matt Groening, so-called relics of Jesus Christ such as the Holy Foreskin and wood from the True Cross, and visions of the Virgin Mary appearing in everything from a condom to a turtle’s underbelly, among other imagery that blends religion, satire, politics, and pop culture.

The swastika appears twice in the painting: Once next to the “Free Indian Legion,” a group of Sikh prisoners of war who fought for Germany, and again on a flag waving behind Japan’s World War II-era emperor, Hirohito, and a samurai in full armory, accompanied by the label “Samurai God.”

Ben Sakoguchi, Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019), detail. Photo courtesy of the artist.

In both contexts, the swastika seems to serve double duty, referencing both its embrace by Nazis during World War II, and also its long history as a symbol of good luck and prosperity in the Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain faiths.

The museum did not responded to inquiries from Artnet News, but a representative told Los Angeles Magazine that “organizing the Biennial was an iterative process, with artworks being considered throughout the curatorial process, up until the opening. Ultimately the artist was not included in the exhibition.”

The first sign that there were any issues with the work came on August 19, when the museum’s chief curator, Courtenay Finn, informed Sakoguchi’s representatives that “questions have been raised about content of Comparative Religion 101, by OCMA education department.”

Ben Sakoguchi, Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019), detail. Photo courtesy of the artist.

In the coming days, the museum sent the artist a list of 17 questions about the work, one of which specifically asked about the use of “xenophobic, violent, and racist symbols, imagery, and language.” There was no specific mention of the swastika. OCMA also asked if Sakoguchi could prepare some audio and visual recordings talking about the piece.

He agreed, and began preparing a selection of slideshows. All seemed well. On September 4, one of the curators, Vicario, told the Los Angeles Times that Sakoguchi’s piece was to be among the biennial’s highlights.

“I find [Comparative Religions 101] powerful because he’s an artist who has been at this for about 40 years who has a visual literacy and ability to illustrate his particular view of the world through this format. It’s very satirical—in a way, it reminds me of part Mad magazine and part political cartoons,” he said. “You get an immediate visceral reaction. It’s completely present and of the moment and unlike anything we saw.”

Ben Sakoguchi, Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019). Photo courtesy of the artist.

A few days later, Sakoguchi sent in his written responses to the museum’s questions, explaining that “I’ve been on the receiving end of xenophobia and racism for most of my existence, and have lived though a long period of time where continued violence, harm, and negative stereotypes were widely tolerated and swept under the rug. I favor selectively shining a light on the offending symbols, imagery, and language, both past and present, as a reminder of our history and of how far we still have to go as a society… and of how vigilant we need to be.”

The museum had also asked how it might prepare for audience members who might be uncomfortable or triggered in some way by the painting and its imagery.

“I have no advice for the museum in that regard. I’ve never believed my role as an artist was to make work that ensured comfort,” Sakoguchi responded. “My paintings are purposefully subject to alternate interpretations, and a reading of Comparative Religions 101 that provokes anger is certainly possible if the viewer is a literalist. But I can’t explain the humor and irony in the work to a literalist, any more than I can explain red to a person who is (red/green) colorblind.”

On September 12, Sakoguchi was told the painting had been rejected “because the museum will not show any work that depicts a swastika,” he said.

He had not yet completed his work on audio-visual slideshows about the painting, a set of supplementary materials that includes 16 examples of pre-Nazi swastikas.

Ben Sakoguchi, Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Through Lee Foley, a director at Sakoguchi’s Los Angeles gallery, Bel Ami, the artist declined to comment further on the controversy. But Foley confirmed what he told Hyperallergic, that the museum then reached out to the gallery to try to arrange a loan of an alternative Sakoguchi work without involving the artist.

When the gallery said it would respect Sakoguchi’s decision not to participate, the museum pushed back in an email.

“Your work needs to assert its rightful place within the biennial as a reminder that communities of color are the social and economic backbone of this country and of California, in particular,” the curators wrote in a letter quoted by Hyperallergic. “Your participation in the biennial is a radical act of cultural resistance and we need your artistic voice to state loudly and clearly that we will not cower to right wing political agendas that are attempting to culturally whitewash our histories and our truths.”

At the last minute, according to the gallery, the museum even offered to include Comparative Religion 101 after all, but Sakoguchi remained unswayed. Ultimately, the biennial opened without him.

“California Biennial 2022: Pacific Gold” is on view at the Orange County Museum of Art, 3333 Avenue of the Arts, Costa Mesa, California, October 8, 2022–February 26, 2023.

More Trending Stories:

Jameson Green Won’t Apologize for His Confrontational Paintings. Collectors Love Him for It