You may recognize Zancan for his lush digital artworks of unearthly flora, which have made him the top-selling artist on the Tezos blockchain. But according to the generative artist, as much as he uses algorithms and code to create his on-chain works, he has sought to get them “off the screen” as well. That is, he wants to give his virtual creations physical dimensions.

“There is a need and a search for the tangible,” Zancan told Artnet News, “or for that extra soul specific to reality.”

His search might finally be at an end. On April 13, the French artist is debuting his new series, titled “Organic Matr,” featuring large-scale canvases drawn from his generative renderings. Though trained as an oil painter, Zancan did not paint these works himself; rather, they represent his latest explorations into “new plotter practices.” In other words, they were produced by robotic collaborators—tools engineered by a company called Artmatr.

Detail of one of the works in Zancan’s “Organic Matr” series. Photo: Matt Coote and Federica Berra, courtesy of Artmatr.

Established in 2014, Artmatr currently runs studios in Israel and Brooklyn, installed with its proprietary painting robots, which are massive, highly sophisticated plotters programmed to paint based on software inputs. These room-sized machines are the products of nearly a decade’s worth of research and development that leans on the expertise of artists and scientists from MIT. Their purpose is to help artists physically realize digital artworks with maximal control and creativity.

It’s a process, said Ben Tritt, the artist and educator who founded Artmatr, allowing for “all the infinite ways that an artist wants to express themselves in translating a flat image into something that has the sensuality and the story that’s embedded in the physical.”

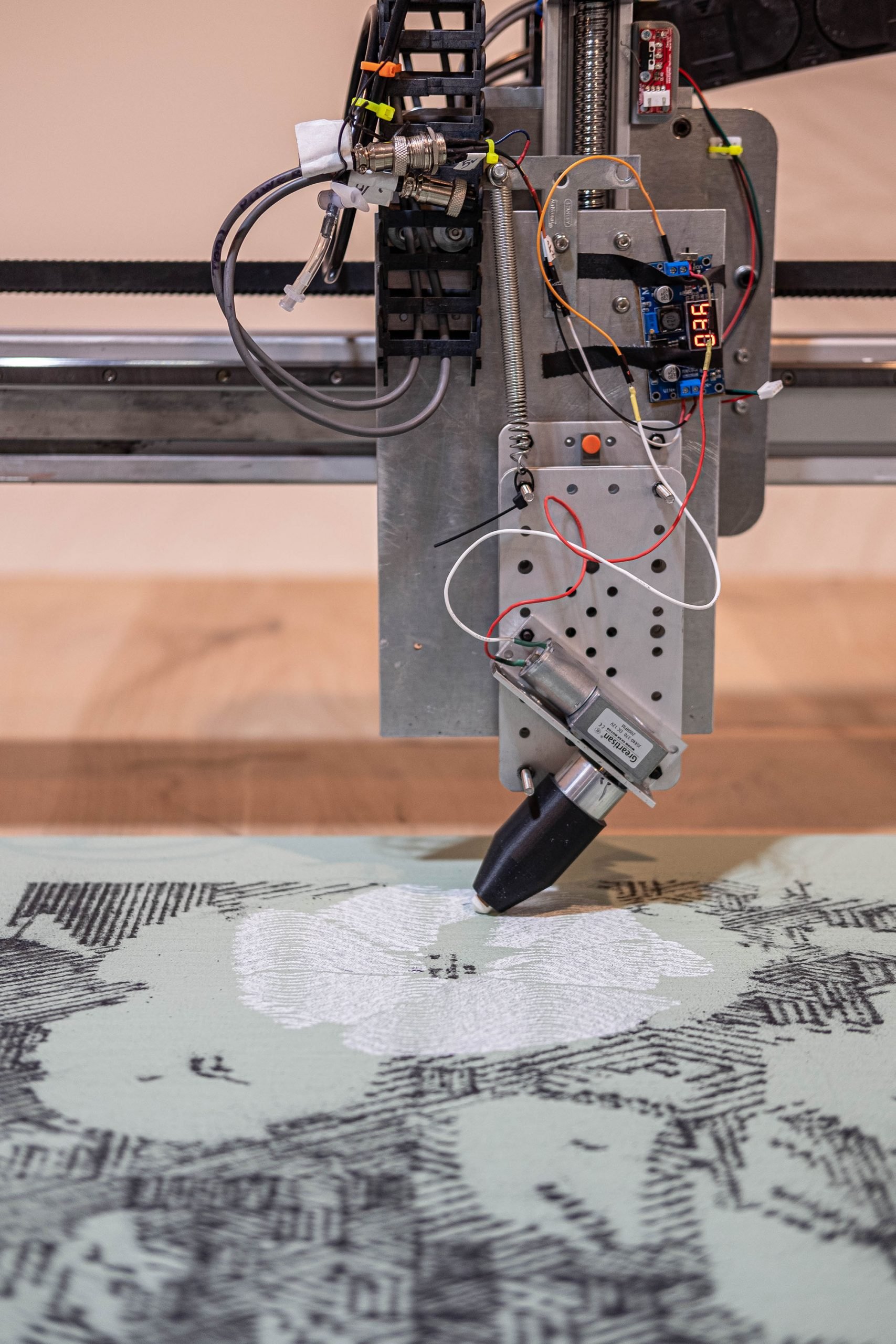

One of Artmatr’s robots at work. Photo: Matt Coote and Federica Berra, courtesy of Artmatr.

That means Artmatr is no plain 3D-printing or fabrication outfit. Its machines enable artists to specify what is painted as well as how—from the ink or brush used, to the pressure and precision of application, to the tilt of the canvas. These paintings are also executed in layers to better build up paint, blend colors, or allow for drying time. In fact, it’s a technique so unique that Artmatr has had to deploy a whole different term to describe it.

“We’re not printing it, we’re not producing it,” Rafael Feitelberg, CEO of Artmatr, told Artnet News. “We’re mattering it.”

And in an age of increasingly screen-based art-making, Artmatr has not lacked for clients. Traditional painters including Barnaby Furnas, Matthew Ritchie, Eric Fischl, James Jean, and Maria Kreyn have availed themselves of the company’s mattering technology, but more so has a growing group of digital and generative artists.

Detail of Matthew Stone, Stone Monument with Offering of Flowers (2022), a digital print on linen. Photo courtesy of The Hole.

British artist Matthew Stone’s A.I. paintings, now showing at The Hole, have been mattered by Artmatr, as have a number of Tyler Hobbs’s latest works for his “QQL: Analogs” exhibition, currently on view at Pace. Of Artmatr’s technique, Hobbs, who also sits on Artmatr’s advisory board, told Artnet News: “It’s fantastic to move beyond simple printing and into truly rich and complex mediums.”

Even the bestselling NFT artist of all time (we can’t name him but you know him) has worked with Artmatr. “We’re inundated,” said Tritt of the demand from digital artists. “We can’t keep up.”

Installation view of “QQL: Analogs” at Pace Gallery. Photo courtesy Pace Gallery.

Zancan himself was introduced to Artmatr by Ryan Roybal of NFT Collective, a Web3 consultancy that represents the artist and has partnered with the robotics lab for this latest launch. For Roybal, quite simply, “what Artmatr is doing is artistry.”

“You’re embodying that artist’s narrative at a much greater scale,” he told Artnet News about the tactility offered by the company. “It’s about playing with physicality and scale to allow people to connect with [Zancan’s] body of work at a deeper emotion because you get to see the line weights behind it or how the charcoal is put on canvas.”

This presence of hand is a cornerstone for Tritt, who described Artmatr’s approach as “art automation that captures the artist’s hand.” Indeed, watching the machines matter one of Zancan’s canvases with an angled piece of white chalk is also to observe how the lines smudge and smear in ways indicating (an almost) human gesture.

Detail of one of the works from Zancan’s “Organic Matr” series. Photo: Matt Coote and Federica Berra, courtesy of Artmatr.

Which gets to the question: Why use robots to do the painting at all?

For Tritt, it’s a matter of automating tasks to enable artists to focus on areas that more intensely require their expertise. “A lot of the art of making paintings is very trivial,” he said. “Mixing colors is not something you have to be a genius to do.” (Artmatr, by the way, has formed partnerships with chemists to aid in its material work and medical appliance makers to provide precision valves to dispense paint.)

He encouraged the view of these robots as tools, akin to how Steve Jobs once described the computer as a “bicycle for our minds.” Said Tritt: “It’s a bicycle for human creativity. It’s allowing people to not be as dependent on what we had previously called talent, and more dependent on their imagination.”

Feitelberg brought up Seurat’s famed Pointillism canvases, each of which took the post-Impressionist about two to three years to complete. “What if he had a machine that could have helped him?” he said. “Would it take away from the breakthrough that was Pointillism?”

He added: “There is something about the purity of the artistic intent and not necessarily the mechanics.”

A Zancan work in progress at Artmatr. Photo: Matt Coote and Federica Berra, courtesy of Artmatr.

It’s all a piece with a digital age where technologies from the blockchain to A.I. have transformed conventional notions of art—wherein artworks can be dreamt up by algorithms, a computer-spawned work is installed at the MoMA, and you too can generate and mint your own Damien Hirst. They’re disruptions, but as well, tools that elasticize how we think about the creativity and human labor that go into art-making.

Zancan, for his part, admitted to feeling both “curious and dubious” when he first learned about Artmatr. “The fantasy of having robots paint is not new,” he explained, “but I knew that the reality was much more complex than the idea.”

And it is. While believing that “there was still a long way to go,” the artist was won over by the enthusiasm, energy, and creativity of Artmatr team, which is made up of artist-engineers. It certainly didn’t hurt too that Hobbs had signed on to the technology.

“The whole time I was at the studio, the robots were working on Tyler’s artwork for his exhibition at Pace,” Zancan said. “It was no longer a fantasy—it was real.”