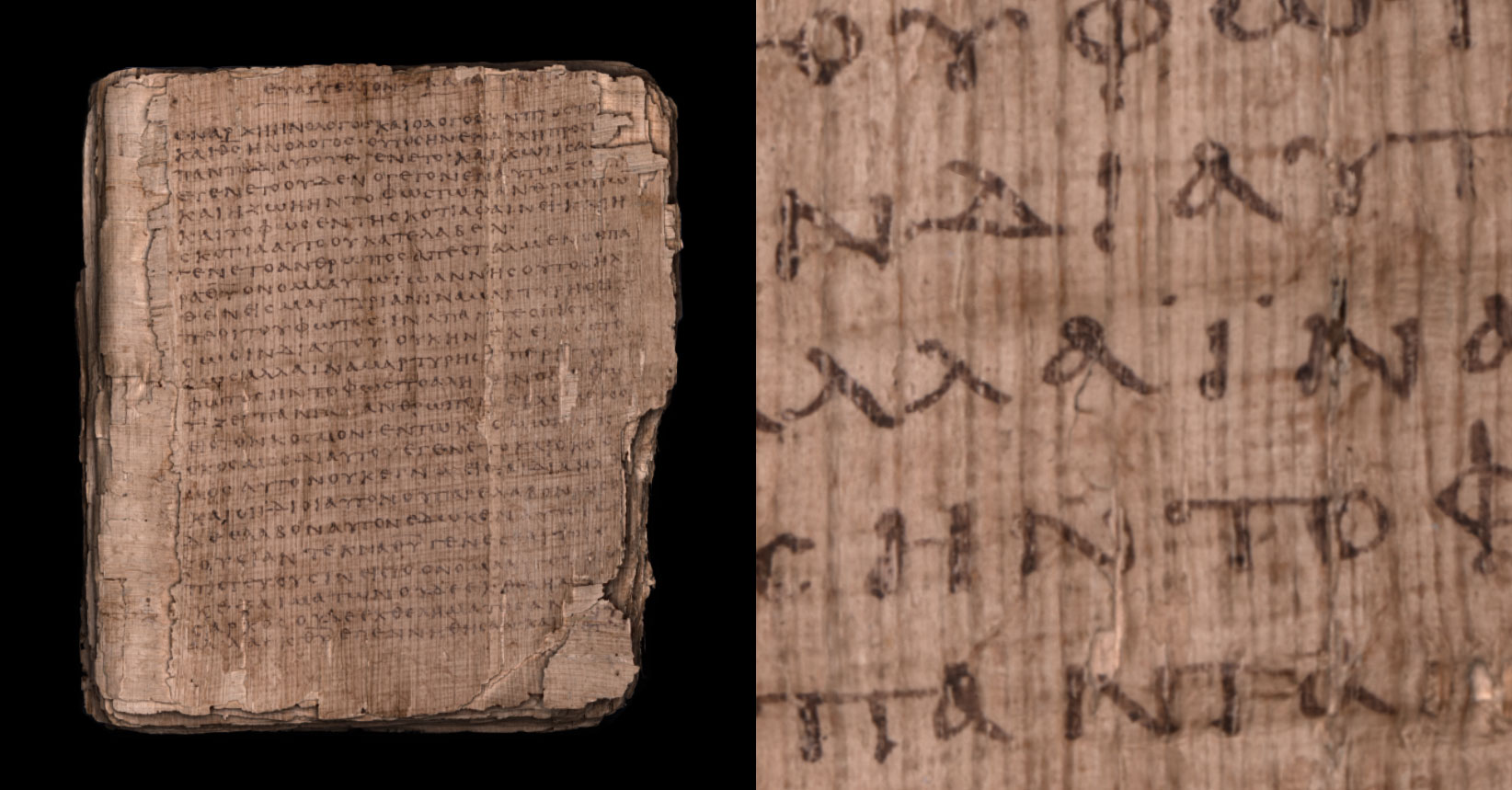

The P66 Manuscript, which dates back to the second or third century, is likely the oldest New Testament manuscript in the world. It lives in a safe at the Bodmer Foundation in Cologny, Switzerland, and is only allowed to be removed by two people: the director of the foundation and the pope. The papyrus document is so fragile that exposure to even the wrong kind of light could cause it to disintegrate into dust. Because of this, very few scholars or researches have been able to look at it since it was first discovered in the 1950s.

However, all that has changed. Now, anyone with a computer or phone can examine the manuscript thanks to Artmyn, a new tech venture that scans art and antiquities and creates detailed, interactive digital facsimiles for both curious viewers and industry professionals to experience on a screen. The company recently collaborated with Bodmer Foundation and scanned the P66. Now you can view it online here.

Detail from Pierre Soulages’s Painting 72.5 x 81 cm, May 3, 1985 (1985). Courtesy of ARTMYN.

The startup, based in Lausanne, Switzerland, began in 2012. At first, it was an academic pursuit at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, but it soon evolved into a more industry-focused enterprise, as its founders realized the wide applicability of the technology they were developing—specifically for the online market.

“The online market has been growing at an impressive rate for the last decade but still has its limitations,” Alexandre Catsicas, Artmyn’s CEO, tells artnet News.

He points to a couple of reasons for this. One is that collectors want the ability to interact with and inspect an artwork before buying it. The other is that there is a lack of standardized certificates of authenticity in the industry.

The technology—a “combination of new generation scanners and algorithms that acquire data, process it, and make it streamable to people online”—was developed with these challenges in mind.

You can interact with the artwork,” Catsicas says. “The software provides people with the capability to zoom in hundreds of times, to tilt and rotate the work, even change the direction of the light so that you can get a sense of each brushwork.”

Artmyn’s cofounders team (Matthieu, Julien, Loïc, Alex).

The company effectively scans artworks. But “scan” is perhaps a misleading term, as their technology doesn’t take just a photo of an object; it takes 100,000 of them, then algorithmically stitches them together. (For reference, the average lifespan of today’s digital cameras is 200,000 images—the company would need a new camera after scanning only two paintings.) The result is an image with a resolution of 1.5 billion pixels—more than a billion more than today’s most high-end digital cameras.

The business is one of many such independent companies exploring this kind of technology that has popped up in recent years. Many, like Great Masters Art or Art Experts, use the tech for forensic analysis or blockchain authentication, looking at an artwork’s materiality, underlying layers, history, and other elements to provide information about its provenance. Others, like Google and its Art Camera project, aim to digitize well-known works, making them accessible to the general public.

Branding itself as the “All-in-one Solution for the Art Ecosystem,” Artmyn has a foot in both camps. It offers digital fingerprints, damage reports, and other technical information for authentication, restoration, and insurance purposes, but the startup also provides a platform for people to explore art virtually.

Indeed, digital scans may offer the general public the most intimate access to rare or fragile artworks. And many people may even prefer technological mediation. At the institutions with which the startup has worked, Catsicas notes that people actually spend more time exploring art through the Artmyn app than the real thing, even when both—the original and the digital replication—are right next to each other.