Photo: via Ottawa Citizen

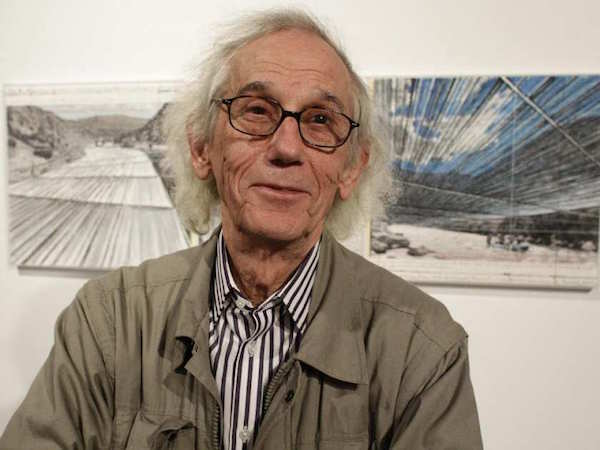

It’s tempting to call Christo Vladimirov Javacheff—popularly known as Christo—a “wrap artist,” and it’s been done before. But the Bulgarian-born, New York-based sculptor, who has recently turned 80, bristles at the suggestion that the 22 environmental interventions he created around the world with his late wife and partner Jeanne-Claude might be summarized so easily.

Indeed, the duo’s nearly 50-year career included projects of every shade, from fabric-wrapped kunsthalles, monuments, and coastlines to massive stacks of empty oil barrels and the infamously orange The Gates, installed throughout New York’s Central Park in 2005. Often requiring decades of preparation and innumerable bureaucratic battles—The Gates, for example, took nearly 26 years from conception to execution—their projects are always mounted for a brief moment and then destroyed, their constituent tons of material parts sent off to be industrially recycled. Up through the early 2000s, the pair was inseparable and extremely active, applying a creative use of fabric to environments both natural and man made. But Christo has been quiet since Jeanne-Claude’s death in 2009.

Until now. On November 6, his first commercial exhibition in over 50 years debuts at Manhattan’s Craig Starr Gallery, and his first large-scale project in a decade, The Floating Piers, will open on June 8, 2016, in Italy’s Lake Iseo. Organized with Italian curator Germano Celant, the 16-day installation will allow visitors and local residents to walk on water for nearly two miles, all atop 200,000 floatable polyethylene cubes covered in vibrant yellow nylon.

artnet News met Christo at the lake to discuss just what it is that he loves about fabric, how he feels about commissions, and why he will never, ever, make art with a cause.

Drawing of Christo’s The Floating Piers (2014).

Photo: André Grossmann © 2014 Christo

Let’s talk about wrapping.

Well to begin, you must understand that some of the works we did, Jeanne-Claude and myself, involved wrapping, and many works were not wrapping. But always a very essential element of our works was the cloth, the fabric, which was the principle material used to translate this nomadic, temporary existence of the work. And of course the work is prepared for many months, even many years, offsite, but then in a very short moment it is installed, much like settlement tents; suddenly the area is changed, for a few days, and then gone forever. The fabric is like our skin in a certain way, a material that is very fragile and vulnerable and dynamic. It is not like wood or steel; it moves, it is very manageable by the human fingers.

Of course, the material is only part of it: the work of art is not the fabric. 6.5 million square feet of floating pink fabric is not the work of art; all those umbrellas are not the work of art. In The Gates, it wasn’t just the gates—it was 7,503 gates across 23 miles, plus the leafless branches of the trees in Central Park, plus Central Park itself, with its walkways, its surrounding high-rise buildings—all that was the work of art. The work of art is everything, all together. And so for our The Floating Piers project, the three kilometers of the floating yellow piers are not the work of art: it’s everything, the water and its movement, the surrounding mountains, the sky.

So the “work of art” is actually comprised of the work of art as it is experienced in context?

It is very difficult to explain it to young people, who have little sense of the real world; they have only the sense of flat screens and virtual reality. It’s so difficult to get them to see what is the real wind, what is the real dry, the real wet. And all of that, that is the work.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin (1971-95)

Photo: Wolfgang Volz via christojeanneclaude.net

It seems that you use the material of fabric to draw our attention to things that already exist in the world, to get us to see the world more actively.

Our works require very physical relations to the things, not only seeing. It’s not about “attention,” like looking at a painting or a photograph; no. Our work is bringing experience, not attention—attention is a very lazy expression. Because you don’t need to see our projects, you need to walk them! You need to spend kilometers around them. We have done urban projects, rural projects, but every single project happens in a space where there is a human presence. We never do projects far away in the middle of nowhere, because we need to have a scale relation—a telephone pole, street, house, rock—to understand how long, how high the work is. If not, then you have no relation between the work and human space. Our works are designed for humans, so that humans can go there and see and feel.

All our work over the last 50 years has two periods: the software period, and the hardware period. The software period is when the work of art doesn’t exist. It exists only in sketches, in drawings that I do, and in the mind of the thousands of people who try to help us—and the minds of the thousands of people who try to stop us. Now, every project develops its own identity in the process of its own creation, and this is why we don’t do commissions. We like to have the freedom for the project to shift and reveal its identity throughout the process. We would have been absolutely wrong to tell you in 1972, when we began Wrapped Reichstag, that we knew what Wrapped Reichstag was. Twenty-four years of getting the permissions and permits taught us what it was.

Drawing of Christo’s The Floating Piers (2014).

Photo: André Grossmann © 2014 Christo

What was the development process for The Floating Piers?

Jeanne-Claude and I had tried to do a project with floating piers twice already in the past, but we were unsuccessful. Now in 2014, while working on a project for Abu Dhabi and the Over the River project, we were having difficulties with both—so I decided to revive the idea of the floating piers. In the early 60s, we had many exhibitions in Northern Italy, so I decided that after 40 years, I wanted to return to Italy to do another project, mostly because I thought that we could probably get the permission faster, because we have friends here. Now, the unusual part of Lake Iseo is that you have that island in the middle that is actually a mountain. And it’s taller than the Liberty Tower in Manhattan, it’s 500 feet taller. And that island, Monte Isola, has 2,000 inhabitants, but there is no bridge to go there—they go by boat. But for these precious 16 days in June next year, they will walk on the water to go there.

What is the role of water in your work?

There are a lot of physical contrasts between the fluidity of the water and the sturdy earth—the land, the road, the tree. The dynamics of the water, whose movement can mesmerize you, and the massiveness of the land, and the contrast is an incredibly inviting and invigorating thing; it is very sensual. The Floating Piers is about walking, not only about watching, and you need to walk it barefoot to feel it even better. This project is unbelievably sexy. Basically, we are making fabric on a huge scale that allows us to translate the fluidity of the motion of the water to fabric, and then into your body.

Drawing of Christo’s The Floating Piers (2014).

Photo: André Grossmann © 2014 Christo

Your works accomplish stunning feats of technical and physical engineering.

No, in fact they are very humble projects, very simple projects, but they need to be put together in an incredibly clever way. People build much bigger projects in the world every day: bridges, skyscrapers, and everything. In fact, our works are not these stunning feats of engineering, they are very simple—but it is sometimes more difficult to make simple things than complicated things. Our projects are only exceptional because they are totally useless, and totally irrational. These projects only exist because Jeanne-Claude and I want to see them: the world can live without them. They exist in total freedom, nobody can buy them or own them, or charge tickets. This irrationality, this uselessness, is part of the work: that is why I’m very much against art that has a cause. Because art with a cause is always propaganda—it can be political propaganda, it can be religious propaganda, or environmental propaganda—but it’s all propaganda. I came from a Communist country and I left in order to make art totally free.

You see, our art has no responsibility. It does not make you feel better, or eat better, or be healthier. What is its meaning? There is none. Art is only done by humans, nobody else. Humans have this incredible pleasure of something that only they can do. And like humans, who live fragile lives and then disappear, the works, too, exist for a moment and are gone forever.

Christo (right) with The Floating Piers project director Germano Celant (center) and Vladimir Yavachev (left),July 2014.

Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2014 Christo