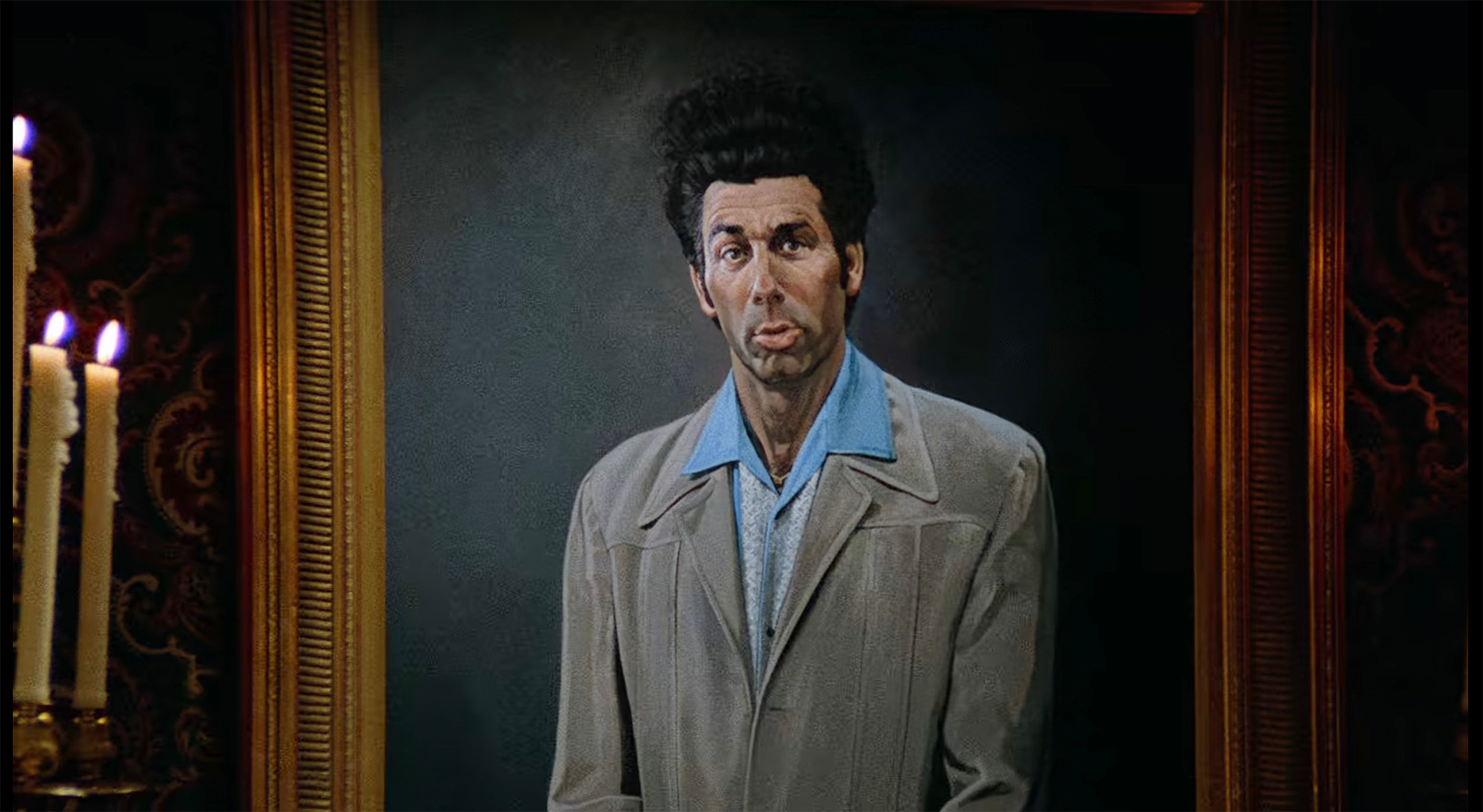

In “The Letter,” episode 21 of the third season of the sitcom Seinfeld, Cosmo Kramer (played by Michael Richards) agrees to have his portrait painted by Jerry Seinfeld’s girlfriend-of-the-week Nina (Catherine Keener), an artist. Like many characters in the show, Nina is fascinated with Kramer’s unorthodox appearance and eccentric behavior, qualities she captures in her larger-than-life painting.

Michael Richards and Catherine Keener in Seinfeld (1989–98). Photo: Screen grab.

As Jerry’s friend George Costanza (Jason Alexander) is guilt tripped into buying one of Nina’s paintings, an elderly couple visiting her studio becomes enamored with the Kramer portrait. In a now-iconic exchange of dialogue, they share their over-articulated impressions of the subject:

“I sense great vulnerability. A man-child crying out for love. An innocent orphan in the post-modern world.”

“I see a parasite. A sexually depraved miscreant who is seeking only to gratify his basest and most immediate urges.”

“His struggle is man’s struggle. He lifts my spirit.”

“He is a loathsome, offensive brute. Yet I can’t look away.”

“He transcends time and space.”

“He sickens me.”

“I love it.”

“Me too.”

Their assessment of Kramer isn’t half bad. The character, based on showrunner Larry David’s neighbor and poker buddy Kenny Kramer—who, for a while, was offering a “reality tour” of his own daily life—lives across the hall from Jerry. Throughout the show, he routinely barges into the latter’s apartment to share his latest get-rich-quick schemes or to raid the pantry. Sometimes both.

Michael Richards holds a script of the final episode of Seinfeld alongside cast and crew members from the hit television show, 1998. Photo: David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images.

A parasite? No doubt—just check Jerry’s grocery bill. Innocent? Possibly. Under all those delusions and ticks, Kramer has a childlike naivety to him. He is well-intentioned and although he has no quarrel stealing their food, actually cares a great deal for his friends.

Transcending time and space? In a way, this is also true. His colorful fashion sense certainly comes from another time period, and while the other characters, especially George and Elaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), routinely battle against society and its sometimes outrageous, sometimes very reasonable standards, Kramer embraces the chaos of the universe and flows with it, always landing on his feet.

None of the big books on the production history of Seinfeld—including Nicholas Nigro’s encyclopedic Seinfeld FAQ: everything left to know about the show about nothing—mention who painted the Kramer portrait, leaving the artist anonymous. This is too bad, as they would have been able to collect significant royalties. Like certain stills from the show—notably, “The Timeless Art of Seduction,” an unnecessarily alluring portrait of George—reproductions of the portrait are being sold all across the internet, providing home decoration for Seinfeld’s enduring and, thanks to Netflix, growing fanbase.

Although the sitcom aired its final episode in 1998, it has remained a prominent force in American popular culture. Fans of the show not only recite its jokes, but also dress like the characters. According to Seinfeld costume designer Charmaine Simmons, Kramer’s vintage style became so popular with audiences that she found herself struggling to find “Kramercore” clothing in thrift stores before they were sold out. “Fashion-wise,” she told The New York Times, “we’ve really created a monster.”

As for Kramer’s portrait, its fate, like its maker, remains a mystery. In the show, it was purchased by the elderly couple for a whopping $5,000. Needless to say, they were much happier with their purchase than George was with his.

As Seen On explores the paintings and sculptures that have made it to the big and small screens—from a Bond villain’s heisted canvas to the Sopranos’ taste for Renaissance artworks. More than just set decor, these visual works play pivotal roles in on-screen narratives, when not stealing the show.