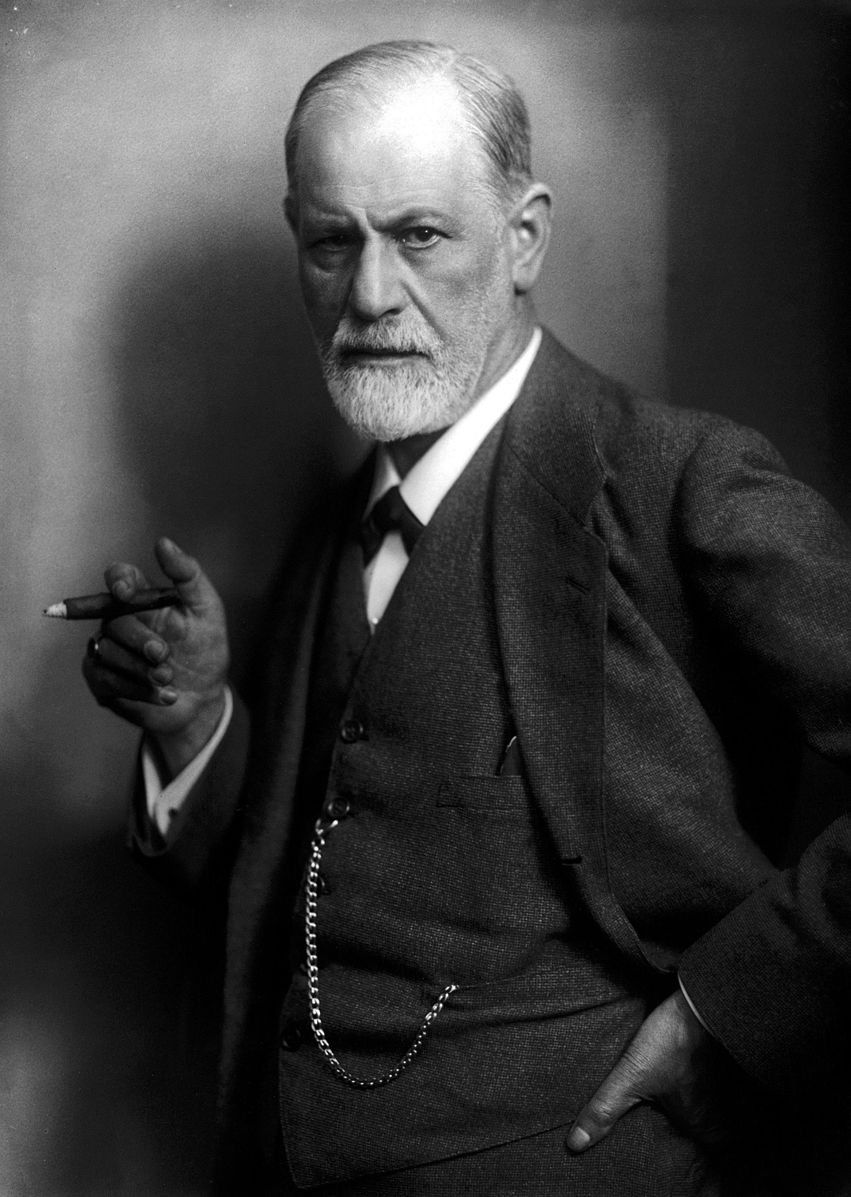

For Sigmund Freud, the interpretation of dreams was a “royal road” to the unconscious. But his belief in wishes fulfilled during sleep became obsolete in 1977, when psychologists discovered that the brain, while in rapid eye movement, lacked the capacity to organize. Since then, our understanding of how the mind works at night has grown increasingly scientific and complex; however, art—which could be thought of as a “waking dream”—offers a separate pathway (or several) with which to approach the unconscious. This selection of works from Post-War & Contemporary Art, live now on Artnet Auctions, awakens artistic stories that penetrate cognitively and chromatically.

Martin Kippenberger, Freud (1990). Available now in Post-War & Contemporary Art on Artnet Auctions (est. $80,000–$120,000).

Martin Kippenberger begins the narrative with his hallucinatory Freud (1990). Acrylic and latex intersect to form a structural, phantasmagorical plane of Mars orange (or blended red and yellow iron oxides) from a mind inflamed with inspiration. Prior to creating the canvas, Kippenberger immersed himself in the German judge Daniel Paul Schreber’s Memoirs of My Nervous Illness, which Freud also studied. Yet the vibrancy of this composition demands a “freer association,” maybe another “architecture of nerves” in “God’s realm,” comparable to Schreber’s. The ambient sounds of Romanian-German musician Michael Cretu and his group Enigma provide a provocative juxtaposition to Kippenberger’s midnight fantasy. Also released in 1990, their album MCMXC a.D. recorded voices that monastically utter alongside slow techno: “The principles of lust are burned into your mind… Do what you want, do it until you find love.” Embedded desires seem to burn bright in the beat—as they do in Freud, which expresses Kippenberger’s innermost seductive layers.

Sol LeWitt, Short Vertical Brushstrokes (1994). Available now in Post-War & Contemporary Art on Artnet Auctions (est. $50,000–$70,000).

Sol LeWitt steps equally toward pitches that bewitch the central nervous system; his symphonic gouache Short Vertical Brushstrokes (1994) dreams religiously and infinitely as well. Critic Rosalind Krauss emphasized the importance to LeWitt of meaning read symbolically downwards, as when interpreting the axes of a cross. His love of classical music, however, resonates subconsciously through these specific verticals. German composer Richard Strauss, for example, incorporated Herman Hesse’s lyrics—“Soul, released from all your defenses, enter the magic, sidereal circle where the gathering of souls commences”—when he wrote his Four Last Songs, and specifically the passage, “When I Go to Sleep.” A powerful, velvety soprano voice (arguably best channeled by Jessye Norman) in the phrases of the tune superimposes delicate strings which coat the psyche; so too does LeWitt, with notes of ochre yellow, rich vermillion, cerulean, opaque white, and ivory black euphorically harmonizing, as if “gathering” endless wake cycles on the page.

Fernando de Szyszlo, Visitante (1988). Available now in Post-War & Contemporary Art on Artnet Auctions (est. $70,000–$90,000).

Relinquished inhibitions function only after dark in Fernando de Szyszlo’s magical domain. In Visitante (1988), psychic portals appear in a surreal figure outside the boundaries of daylight. An ancient form of mythological cubism, proximate to his native Peru, creates a turbulent headspace in gradient carmine red and ultramarine rose, to express the core instincts of an impulse-ridden id. Near the conception of the painting in 1988, Peruvian literature Nobel Laureate Mario Vargas Llosa released his subversive novel In Praise of the Stepmother, which directly mentions de Szyszlo. The book examines the secret, carnal drives of a married couple, each individually drawn to irresistible passions. In its second chapter, the wife, Doña Lucrecia, returns to bed with her husband, Don Rigoberto, who says, from out of a dream-fantasy, “‘Why did you leave me, darling?’” Erotic anxieties wash over her, and, as Vargas writes, they open her pores—a sensation visually parallel to the steaming emanation of de Szyzslo’s visitation.

Mimmo Rotella, Carabiniere a cavallo (1963). Available now in Post-War & Contemporary Art on Artnet Auctions (est. $80,000–$120,000).

In Carabiniere a cavallo (1963), Mimmo Rotella channels a freed cinematic cityscape. Walls of Italian street posters encouraging enrollment in the national police force lacerate through décollage into pockets of bared crimson, blue, yellow, and white that seem to mechanize psychologically buried feeling. In the same year in which Rotella executed this piece, director Vittorio De Sica assembled the emotions of an at once joyous and real moment through his colorful anthology Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. In a climactic scene, Sophia Loren’s character dances to Henry Wright’s rendition of the song Abat-Jour (“Lampshade”) for Marcelo Mastroianni as he bunches his limbs into a fetal position, visibly longing for her. She removes several of her outfit components as Wright sings “Lampshade, while you shed the blue light, maybe you are also looking for someone who is no longer there.” The record and its charming accordion notes set Loren’s dance, and Mastroianni’s untethered craving, into a dreamscape not unlike Rotella’s.

Post-War & Contemporary Art is live on Artnet Auctions through November 18, 2021.