The 130-year-old Aunt Jemima brand of pancake mix, waffles, and breakfast syrup will be no more, the Quaker Oats company announced on June 17.

The PepsiCo-owned company is retiring the brand and its namesake character, acknowledging that “Aunt Jemima’s origins are based on a racial stereotype,” it said in a statement.

“While work has been done over the years to update the brand in a manner intended to be appropriate and respectful, we realize those changes are not enough,” added Kristin Kroepfl, vice president and chief marketing officer of Quaker Foods North America.

New packaging will be introduced in late 2020, with a name change to follow.

Named after “Old Aunt Jemima,” a minstrel song composed by African American comedian and performer Billy Kersands, the brand and its namesake character were introduced in 1890. The first face of the product was Nancy Green, a former slave.

“The removal of the Aunt Jemima name and icon for the Quaker Oats brand is a long time coming. For generations, the brand has profited from the racist desire to have a Black woman as slave and servant to Whites,” Bridget Cooks, author of Exhibiting Blackness and associate professor of art history and African American studies at the University of California, Irvine, told artnet News in an email.

Aunt Jemima, then and now. Image courtesy of Quaker Oats.

In early years, Aunt Jemima was shown serving white families. More recent updates have replaced her kerchief with pearl earrings and a lace collar.

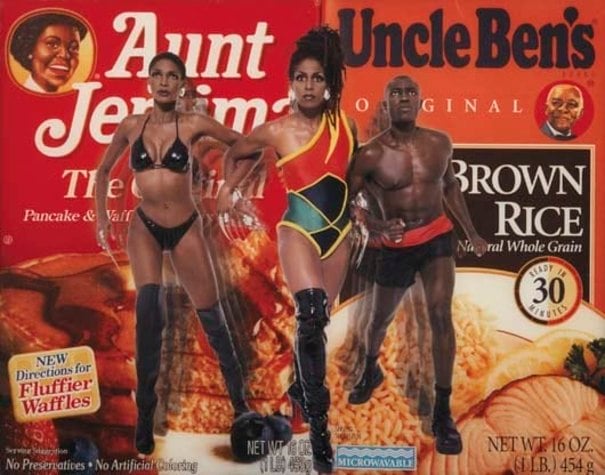

Soon after Quaker broke the news, Mars Inc. announced that it would be rethinking its Uncle Ben’s brand of rice, which features a black rice grower, amid similar charges of racial stereotyping. Conagra Brands followed suit, saying it would review the packaging of Mrs. Butterworth’s syrup, which is “intended to evoke the images of a loving grandmother.” The bottle, criticized as being reminiscent of a “Mammy” figure, was modeled after Thelma “Butterfly” McQueen, the African American actress who played Prissy in Gone With the Wind.

“That Aunt Jemima is a racist symbol is not a new realization for Black people or for company, nor is the icon the only one,” said Cooks. “What’s more important than the acknowledgment and removal of these symbols is the larger issue of Black equality on the corporate level and the corporations’ relationship to Black lives.”

Meanwhile, the Land O’Lake’s brand of butter, phased out its mascot of a kneeling Native American woman, sometimes called Mia, in April after 92 years. The company did not acknowledge Indigenous groups who had called the logo offensive, choosing instead to emphasize the rebrand’s new focus on farmers, according to AdWeek.

Aunt Jemima’s fall comes after years of criticism.

“This Aunt Jemima logo was an outgrowth of Old South plantation nostalgia and romance grounded in an idea about the ‘mammy,’ a devoted and submissive servant,” Riché Richardson, an artist and associate professor in the Africana Studies and Research Center at Cornell University, wrote in a 2015 opinion piece in the New York Times. “Visually, the plantation myth portrayed her as an asexual, plump black woman wearing a headscarf.”

Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972). Collection of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, California; purchased with the aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts (selected by the Committee for the Acquisition of Afro-American Art). Photo by Benjamin Blackwell courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Over the years, the Aunt Jemima character has appeared in works by numerous artists, including Betye Saar, who used the character in a 1972 mixed-media sculpture titled The Liberation of Aunt Jemima. In the work, the character stands in front of a backdrop of Aunt Jemima logos, condemning the brand’s glorification of subservience.

“I created The Liberation of Aunt Jemima in 1972 for the exhibition “Black Heroes” at the Rainbow Sign Cultural Center, Berkeley, California,” Saar told Artnet News in an email. “The show was organized around community responses to the 1968 Martin Luther King Jr. assassination. This work allowed me to channel my righteous anger at not only the great loss of MLK Jr, but at the lack of representation of black artists, especially black women artists.”

“I transformed the derogatory image of Aunt Jemima into a female warrior figure, fighting for Black liberation and women’s rights,” she added. “Fifty years later she has finally been liberated herself. And, yet more work still needs to be done.”

See more artworks by artists who have tackled the Aunt Jemima stereotype below.

Joe Overstreet, The New Jemima (1964/1970). Photo courtesy of the Menil Collection.

Murry DePillars, Aunt Jemima (1968). Photo courtesy of the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia.

Jeff Donaldson, Aunt Jemima and the Pillsbury Doughboy. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Faith Ringgold, Whose Afraid of Aunt Jemima (1983). Photo courtesy of the artist.