Artists and writers are generally considered distinct from one another within the capital-A arts; we award international prizes to specialists in their genre. But what about instances in which they are the same—two sides of the same coin? The creative impulse that drives every maker to make seemingly knows no bounds; visual artists very often work across genres, and it follows that many writers would be drawn to conjure worlds outside the written word. Children’s book authors are perhaps the most well-known for illustrating their own texts, but are often dismissed because of the youth of their perceived audiences. Authors from P. L. Travers to J.R.R. Tolkien have taken the stance that there is no such thing as writing for children; but illustrations, whether for books aimed at children or adults, offer readers the ability to further engage with the story and better understand the full scope of the author’s vision.

Inspired by the exhibition “The Little Prince: Taking Flight” (on view through February 5, 2023) at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, which presents Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s original manuscripts and paintings for The Little Prince, we’ve gathered here a few shining examples of authors that have illustrated their own writings—from Alasdair Gray’s art-historically rooted frontispieces to Beatrix Potter’s whimsical illustrations of anthropomorphic animals.

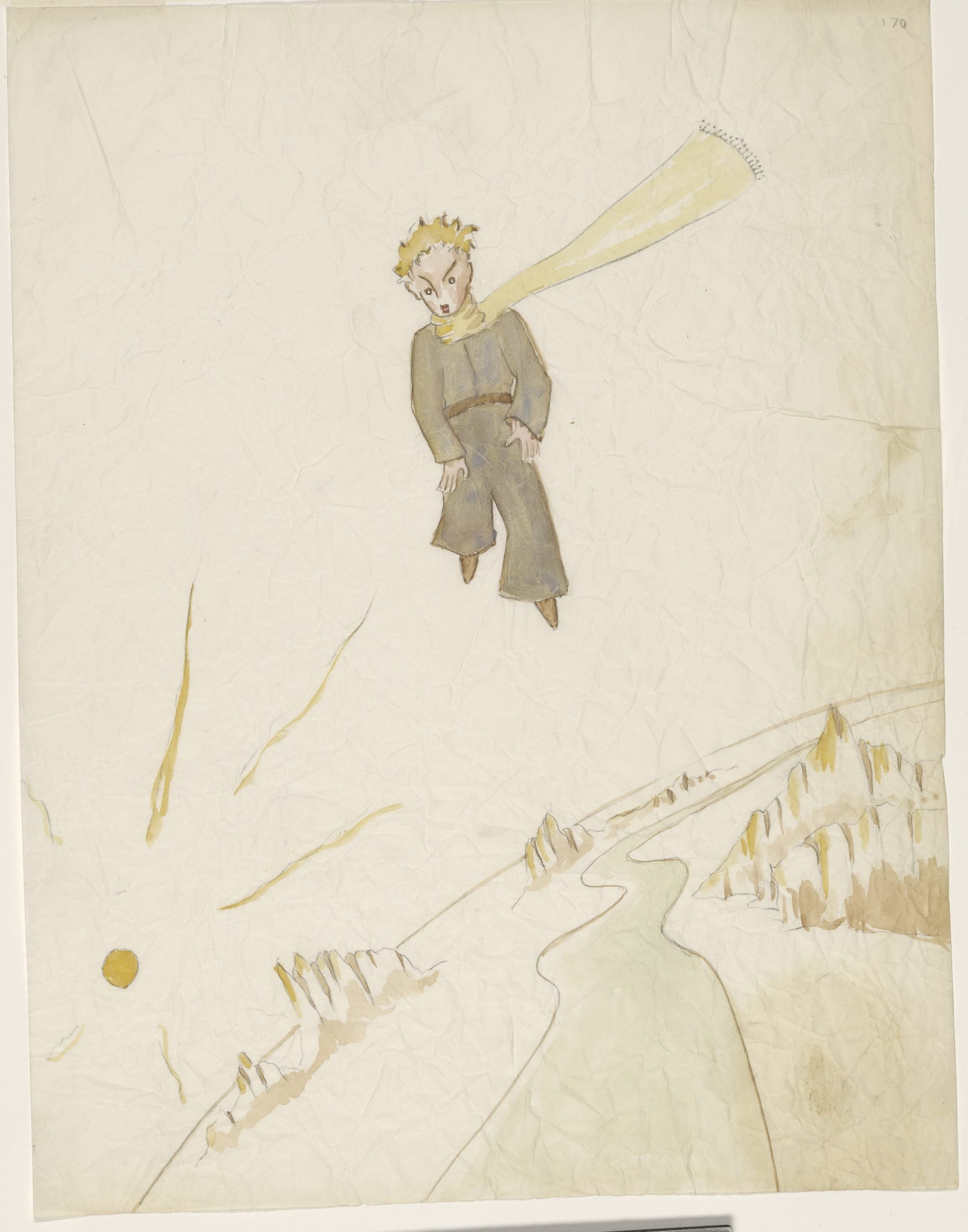

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince (1943)

Left: Portrait of Saint-Exupéry in pilot outfit, Buenos Aires (1930). Purchased on the Drue Heinz Twentieth Century Literature Fund, 2021. Collection of the Morgan Library and Museum. Right: Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The little prince in the desert, in front of bones and cacti (1942). Collection of the Morgan Library and Museum.

Author and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry served in the French air force beginning in the early 1920s until 1940, when France fell to the Nazi invasion. He then went into exile in the United States, where he remained until 1943, and it was during this period that he created one of the world’s most famous and beloved books and characters: The Little Prince (1943). Drawing from his own experiences as a pilot and world traveler, the tale follows a child prince on his journey to different planets, each inhabited by a single adult that is an allegorical representation of a personal or societal shortcoming. Saint-Exupéry was asked by Life photojournalist John Phillips about the inspiration for the character of the prince, to which the author gave an appropriately enchanted reply. He told him that one day he saw a childlike figure on what he had assumed was a blank piece of paper. He asked the figure who he was and was met with the reply: “I’m the Little Prince.”

Saint-Exupéry’s remarkable watercolors and sketches illustrating the prince and his travels—oft marred by the stain of a coffee cup or singed from the butt of a cigarette—on view at the Morgan offer insight into Saint-Exupéry’s creative process and the development of the Little Prince himself.

Beatrix Potter, The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1901)

Left: British author and illustrator Beatrix Potter (1892). Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Right: Illustration from The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1901).

Beatrix Potter’s series of children’s books are for many their first foray into reading. The tales of Peter Rabbit, Benjamin Button, and Tom Kitten, among numerous others, have become as recognizable by their names as their illustrations. Potter began illustrating before writing and was inspired by all manner of fairy tales and fantasy. Some of her first drawings were actually illustrations made for beloved classics such as the Brer Rabbit stories and Puss-in-Boots. Alongside this hobby of illustrating other writer’s stories, Potter began creating her own fantasies using her pets—kittens, rabbits, even a guinea pig—as characters. People who know Potter personally described how she often sketched images of animals and countryside in so-called “picture letters,” and in 1901 she turned one of these into her very first book: The Tale of Peter Rabbit. Rejected by numerous publishers, it was not until Potter privately published a version of it herself that it was picked up by Frederick Warne, who published it commercially, and followed it with 20 more illustrated books.

Like Saint-Exupéry, Potter is also the subject of a current exhibition, “Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature,” on view at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, through January 8, 2023. The exhibition survey’s Potter’s artistic output throughout her life, revealing that her work as an artist went far beyond cute woodland creatures. She was a talented naturalist and created numerous highly detailed watercolors of flora and fauna, and she knew how to render what was seen under a microscope—which she used to illustrate scientific papers; her essay, On the Germination of the Spores of the Agaricineae (1897) was presented at the Linnean Society (shared by her uncle, as women were not allowed to attend). Potter had a particular interest in mycology (or the study of fungi) and mosses too, and her meticulous studies of these are now held in the collection of the Armitt Library, Ambleside, U.K.

Alasdair Gray, Lanark: A Life in Four Books (1981)

Alisdair Gray, frontispieces of “Book One” and “Book Two” from Lanark: a Life in Four Books (1981). Courtesy of the Alasdair Gray Archive.

Written over the course of 30 years by Scottish author Alasdair Gray, Lanark: A Life in Four Books (1981) has been heralded as a landmark of 20th-century fiction and developed a cult following for its unique and ingenious storytelling. Lanark is comprised of four books that are arranged out of chronological order (three, one, two, four) and weave the story of main character Lanark’s life (as well as his past) against the backdrop of a reimagined Glasgow, one that is dystopian and at times surreal. Unlike some of the other authors on this list, Gray maintained a known and thriving artistic practice outside of his writing, so it is no surprise that this publication—which could be considered his magnum opus—is richly illustrated by Gray himself. The illustrations within Lanark show that Gray had a wide-ranging knowledge and understanding of art history. The frontispieces of the four books all draw heavily from canonic works of art; the composition of the opening illustration for Book Two is fundamentally the same as in De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1555) by Italian anatomist Andreas Vesalius. The frontispiece of Book One, however, is far less faithful to its inspirational antecedent. Drawing the general compositional arrangement from the frontispiece of Francis Bacon’s Instauratio Magna, Gray has made several significant changes, including adding a version of the city of Glasgow’s “Let Glasgow Flourish” motto as the honorific inscription at the base of the two columns, and depicting the city of Glasgow in minute detail between them.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit (1937)

British writer J.R.R. Tolkien at Merton College, Oxford. Photo: Haywood Magee/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

The Hobbit (1937) by J.R.R. Tolkien introduced the world to Middle Earth, the setting for arguably the most influential fantasy series in history. The book was originally published with 20 illustrations—portraying everything from the bucolic Shire to the dragon Smaug on his hoard of gold—and two maps of Middle Earth, all created by Tolkien himself. The original dust jacket, too, featured a painting by Tolkien, which shows the Misty Mountains and Mirkwood forest, both of which the hobbit Bilbo Baggins navigates over the course of the story on his way to the Lonely Mountain.

Tolkien was famously in the midst of doing paperwork when he was struck by the jolt of inspiration that led him to jot down what would become the first line of The Hobbit: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” Tolkien spent roughly the next seven years writing the book as well as illustrating the expansive fantasy world in which it is set. Though it featured an impressive number of illustrations, during preparations for the book’s 75th anniversary it was discovered that Tolkien had in fact created over 100 illustrations, many of which had been all but forgotten in the archives of Bodleian Library in Oxford. The works are largely watercolors, ink line drawings, and sketches, and together they reflect Tolkien’s many visual influences. Chief among these was William Morris, the 19th-century polymath and pioneer of the Arts and Crafts Movement, which can be seen in the harmonious color palettes and avoidance of overly fussy compositions. Norse mythology and visual culture also were key sources of inspiration for Tolkien, as is reflected in the runic border of the dust jacket.

William Makepeace Thackeray, Vanity Fair (1848)

William Makepeace Thackeray, opening spread of Vanity Fair (1848).

From the outset, British novelist William Makepeace Thackeray always intended for Vanity Fair (1848) to be complemented by illustrations throughout. A Victorian-era book set in the Napoleonic England, Vanity Fair was first published as a monthly serial before being issued as a single complete volume. The serialized nature of the initial publication may have been a key motivation for Thackeray’s extensive illustrations; the first letter of each chapter (or issue) is included within the context of a drawing, and nearly every chapter includes a full-page image, as well as one or two half- or quarter-page illustrations. Vanity Fair follows the story of two women, Becky Sharp and Amelia Sedley, as they navigate a satirized version of early 19th-century high society. Despite being set a generation before, it is intriguing that Thackeray opted to illustrate his characters in then-contemporary garb. Of the artistic decision, Thackeray stated that he felt the earlier style of clothes was simply too “hideous” to portray—but it also worked to make the characters as well as themes of the book more relatable to the audience, despite the distance of time.

The illustrations inside Vanity Fair have a distinctly caricature-esque slant to them, which guides readers’ feelings and understandings of the characters. Thackeray packed his depictions with detail, but was ultimately displeased with how they were finally printed due to the shortcomings of 19th-century printing technology—the originals were likely much sharper in their rendering than what we see on the page today.

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures Underground (1862–64)

Left: English mathematician, writer, and photographer Charles Dodgson, also known as Lewis Carroll (1863). Photo: Oscar Gustav Rejlander/Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Right: Carroll’s illustration of Alice from Alice’s Adventures Underground manuscript (1862–64).

Though the legacy of Charles Dodgson, better known by the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, has undergone extensive reevaluation in recent decades, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and the other books of the series remain some of the most famous and highest-selling children’s books of all time. The illustrations of the first edition were done by Sir John Tenniel and have come to be the most recognized portrayals of Alice and the many other characters that inhabit Wonderland. What is less known, however, is that Dodgson himself created 37 ink drawings to illustrate the original manuscript, titled Alice’s Adventures Underground (1862–64), laying the foundation for the tone and the many iconic vignettes associated with the tale. Early in the story, for example, Alice grows exponentially in size after eating an enchanted cake, causing her to become trapped inside. Dodgson captures the claustrophobia (and, frankly, for many children, terror) of the scene by drawing Alice curled up within the harsh border of the page, pulling up her knees and reaching for her skirt as if in an effort to fit in a shrinking space. Elsewhere, an enraged Queen of Hearts is shown screaming at Alice from the margin of the page.

The original manuscript was gifted to Alice Lindell, who was the inspiration for the series’ main character and whose relationship with the author became the subject of contemporary criticism of Dodgson. It eventually passed through the hands of several collectors before being given to the British Library.