Barbara Rose, the fierce but flexible critic best known for helping to usher in the new vanguard of Minimalism in the 1960s, died on Friday in Concord, New Hampshire. She was 84.

Rose, who was diagnosed with breast cancer a decade ago, made her first major imprint with the 1965 Art in America essay “ABC Art.” The article, remembered for defining the terms of an emerging Minimalist sensibility, in fact linked a range of tendencies together to make a case for artists whose work contrasted “violently with the romantic, biographical Abstract-Expressionist style which preceded it.”

The usual suspects, including Donald Judd and Robert Morris, were central to the essay. But so were others who did not come to mind for other critics, including the choreographer Merce Cunningham, the composer La Monte Young, the bygone European Constructivist Kazimir Malevich, the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, and the writers Alain Robbe-Grillet and Gertrude Stein.

“This article could have been called ‘Art Barbara Likes, Books Barbara’s Reading, Movies Barbara’s Seen, Music Barbara Listens To,'” she said in an Art in America interview 50 years later.

More than anything, the article provided evidence of Rose’s critical eclecticism and her drive to ground contemporary art in broader historical and contemporary trends.

Rose was born in Washington, DC, on June 11, 1936, to a shopkeeper and his wife, a homemaker. She studied at Smith and Barnard Colleges before attending graduate school at Columbia University, where she trained under the revered art historian Meyer Schapiro. His intellectual elasticity, which combined rigorous close readings with a Marxist sense of context and social history, informed her later work.

In 1961, Rose traveled to Pamplona, Spain, on a Fulbright fellowship and was followed there by Frank Stella, whom she married that November in London. The critic Michael Fried, who would later encourage her to write criticism, was their witness.

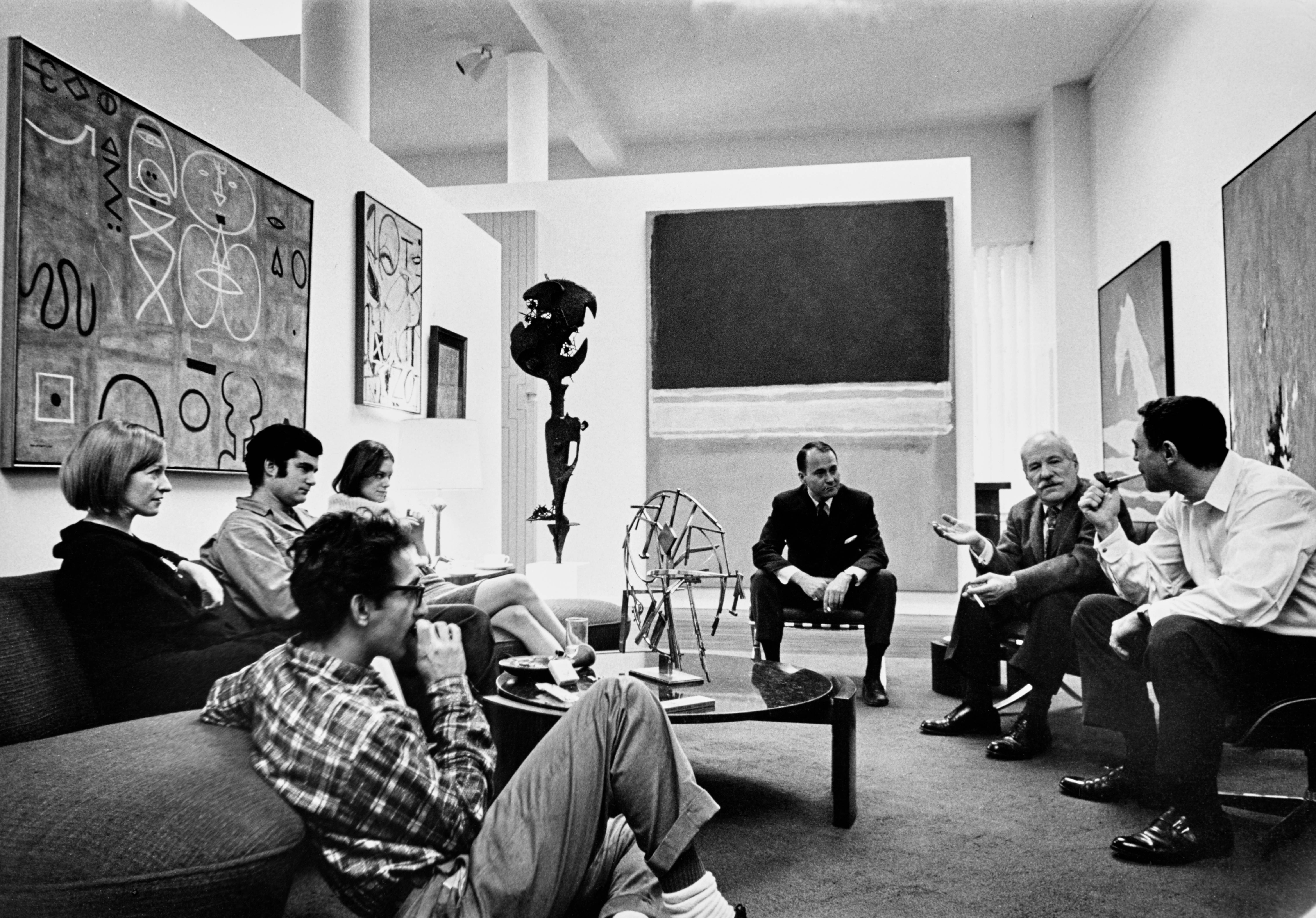

Upon their return to New York, Rose and Stella moved into an apartment near Union Square and had two children. Rose later fell into the circle of the critic Clement Greenberg, who she remembered holding “Maoist sessions in his apartment.”

“You had to denounce certain people and agree with Clem,” she recalled. “One was Al Held and the other was Reinhardt, which left me conflicted. Clem would go: ‘Ad’s a stinker, right?’ And everybody would repeat: ‘Ad’s a stinker.’ And I’d say, ‘No, Ad’s not a stinker.’ And this would go on.”

By 1969, she split from Stella and began to reassess her relationship with Minimalism, which quickly appeared moribund. The next year, she was named the inaugural director of University of California’s new museum at Irvine and spent large parts of the 1970s championing under-recognized painters, including Helen Frankenthaler.

In 1983, while she was a senior curator at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, she organized Lee Krasner’s first museum retrospective, which traveled across the United States and to the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

But she did not work long at the museum, where she was dogged by complaints about conflicts of interest after the institution bought works from her third husband, lyricist Jerry Leiber. (Rose, who was married four times, remarried her first husband, Richard Du Boff, in 2009.)

Her interests in painting deepened over the final 50 years of her life. In 1979, she organized “American Painting: The Eighties” for the Grey Art Gallery at New York University, boldly declaring that artists including Elizabeth Murray and Susan Rothenberg were the future. She curated a related show, “The Nineties,” at André Emmerich Gallery in 1991.

Her most recent major exhibition, “Painting After Postmodernism,” opened in 2016 at at Vanderborght and Cinéma Galeries/the Underground in Brussels, and included 16 American and Belgian artists.

Rose, perhaps reflecting on the longue durée of her career, linked the show back to her earliest interests in the exhibition’s catalogue.

“Minimal reductiveness,” she wrote, “can now be seen for what it is: a transitional step in the history of art, one necessary in order for painting to gain new freedom in favor of the play of the imagination.”