Over the years, the biggest fans of Jean-Michel Basquiat have had a strange way of showing their affection: They’ve just about drowned him and his work in tired romantic clichés.

He’s supposed to be a tortured soul overflowing with passions that pour out through the tortured pictures he paints. One writer likened him to “a preacher possessed by the spirit,” an image that comes dangerously close to primitivist stereotypes. A curator insisted that Basquiat’s art channeled “his inner child,” the kind of talk that could easily veer into ideas of the Noble Savage. Basquiat himself complained that critics had an image of him as “a wild man running around—a wild monkey-man.”

To this day, he’s almost always billed as being more in touch with his emotions and the passions of urban life than with the orderly reasoning of post-Enlightenment culture.

Edo Bertoglio, Jean-Michel Basquiat wearing an American football helmet (1981). Photo: © Edo Bertoglio, courtesy of Maripol, Artwork: © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 & The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Luckily, a show opening in New York lets us see a very different, much smarter and more complex artist than that, one who has more in common with conceptualists like Hans Haacke and Hanne Darboven than with Hollywood’s earless van Gogh—a Basquiat who is an artist of words and thoughts, on the order of Lawrence Weiner and Jenny Holzer, not of instincts and inchoate emotions.

That’s the artist on view in “Jean-Michel Basquiat,” a concise survey that opens March 6 at the new Brant Foundation venue in the East Village. (Tickets are—or were—free, but they have already run out for all 10 weeks of the show; maybe the Foundation will consider opening to the wider public on some Mondays or Tuesdays, which are currently reserved for school groups.)

Installation view of “Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Photos: Tom Powel Imaging, Copyright Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Courtesy The Brant Foundation.

The exhibition is a version of one that ran last fall at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, where it was organized by Dieter Buchhart. In New York, though we only get about half as many pictures, the shrinkage is partly compensated by the addition of some excellent works from the various private collections.

Except for the very earliest collages and graffiti works, and the later collaborations with Andy Warhol, most of Basquiat’s major moments and modes are represented. But for an artist who died at 27—an artist who only ever had the chance to make “early work”—the 70 pictures in the Brant show, displayed across four elegant, light-filled floors, may give just the focused view that we need.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Per Capita (1981). © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Courtesy The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut.

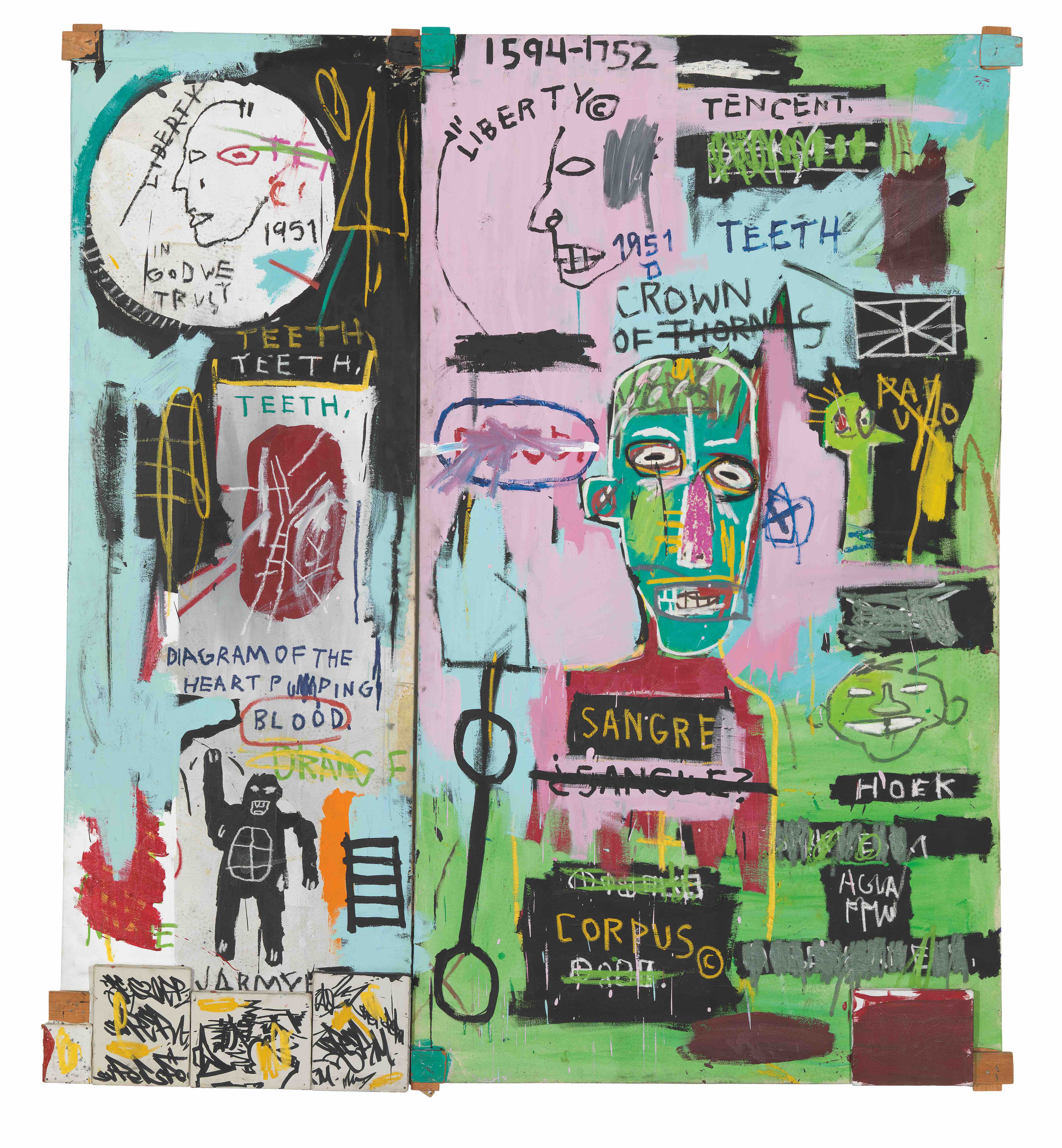

Basquiat is always described as one of the central stylists of 1980s Neo-Expressionism, and it’s easy to get lost in the attractive and exciting—but fundamentally conservative—look and touch of his paintings. In the Brant show, however, I was struck again and again by works where content seemed to matter more than form.

A canvas like Per Capita, a 1981 work from the Brant Foundation’s own collection, overflows with information. One end of the painting is a list of American states followed by the annual incomes of their inhabitants. The rest of the painting is scattered with bits and pieces of graphs and numerical tables. Hollywood Africans, a 1983 painting from the Whitney Museum, is a compendium of all-capped words that relate to the title, usually via some kind of political take on the subject: “SUGAR CANE INC.,” “TOBACCO,” “WHAT IS BWANA?”

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Museum Security (Broadway Meltdown) is displayed at Christie’s London in 2013. Photo by Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images.

A piece called Museum Security, from that same moment, overflows with accusatory words like “RADIUM,” “ASBESTOS,” and “HOOVERVILLE.” All three paintings remind me of the biting lists that Hans Haacke compiled of a slumlord’s real estate holdings, or of the corporate entanglements of the Guggenheim Museum’s trustees. Similarly, a lot of Basquiat’s paintings seem to be as much about simply pointing at things that concern him as they are about choosing how to do the pointing.

Deep down, he’s an artist concerned with inventories, so his pictures have much in common with the tidy cataloging of Darboven. The lack of polish in Basquiat’s style may be about achieving an utterly minimal, frictionless kind of indication—a kind of painting degree zero that parallels Haacke’s typed lists—rather than expressing basic or “primitive” emotions. Basquiat’s scrawls, that is, may really avoid having any style at all, and their ties to the well-worn look of European Expressionism, or to its 1980s retreads, may be almost accidental. When we see a similarity to Expressionist art, we’re indulging in the kind of “pseudomorphism” that the Institute of Advanced Study scholar Yve-Alain Bois has railed against.

Installation view of “Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Photos: Tom Powel Imaging, Copyright Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Courtesy The Brant Foundation.

Although Basquiat’s paintings are almost always linked to the raw emotions of graffiti, it’s important to remember that his own most important interventions on city walls consisted of pungent and concise bits of text. “4 THE SO-CALLED AVANT-GARDE.” “A PIN DROPS LIKE A PUNGENT ODOR.” If they were rendered in neon or carved in stone, these could just about pass as maxims by Jenny Holzer.

“We wanted to do some kind of conceptual art project,” explained Al Diaz, Basquiat’s spray-painting partner, in the 2010 Basquiat documentary The Radiant Child. That’s not the kind of thought that springs from an “inner child.”

Jenny Holzer from poet Wislawa Szymborska on the outside of the Portland Museum of Art in Portland. (Photo by Tim Greenway/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images)

If Haacke and Holzer don’t come to mind at once in looking at Basquiat’s art, I think that’s because of another layer he adds to his “information.” He’s showing how the kind of order and transparent meanings that such white artists take for granted were not made equally available to black people and black artists when they confronted America’s majority culture. The assumption of cultural stability and transparency that information-based art is built around just wasn’t part of the lived experience of many African Americans, at least in New York in the early 1980s. Government statistics and Hollywood movies depended on ideas and images of blackness—and of society in general—that didn’t necessarily map onto what black lives were really like. Haacke could observe a slum landlord’s machinations from on-high; many African Americans suffered them from the inside.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Discography II (1983). © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Courtesy The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut.

The “distortions” in Basquiat’s pictures are not there to deliver an Expressionist style; they are distortions that are really out there in the world, the filters of race and oppression that came between a black artist and the things he wanted to point to.

By contrast, Basquiat’s art can become orderly and almost Apollonian when it digs into modern jazz, with its unquestionable roots in black culture. A painting like Discography II, a recent Brant acquisition, gives a stable and systematic account of the first recording session that Miles Davis led under his own name, with the title and take of each song set down in orderly white script on a black background. The painting represents the world as Basquiat might have preferred to render it, if only circumstances allowed.

Correction: Because of incorrect information supplied by a publicist, an earlier version of this article stated that the exhibition includes works from the Brant Foundation that were not on view at the Fondation Louis Vuitton. In fact, all works from the Brant Foundation on view in New York were also on view in Paris.

Blake Gopnik is the author of Warhol, a comprehensive biography of the Pop artist forthcoming from Ecco at HarperCollins.