One could be forgiven for failing to understand how the sale of a painting bought in 1983 for $15,000 and resold last month for $30.7 million, could ever be deemed “disappointing”. After all, the price increase represents more than 2,000 times the original purchase price.

But add in the consignor’s high hopes for a nine-figure price tag—or upwards of $100 million—and a heavy dose of family dysfunction, and you’ll start to understand the forces behind a $100 million retaliatory lawsuit now at play in the New York State Supreme Court.

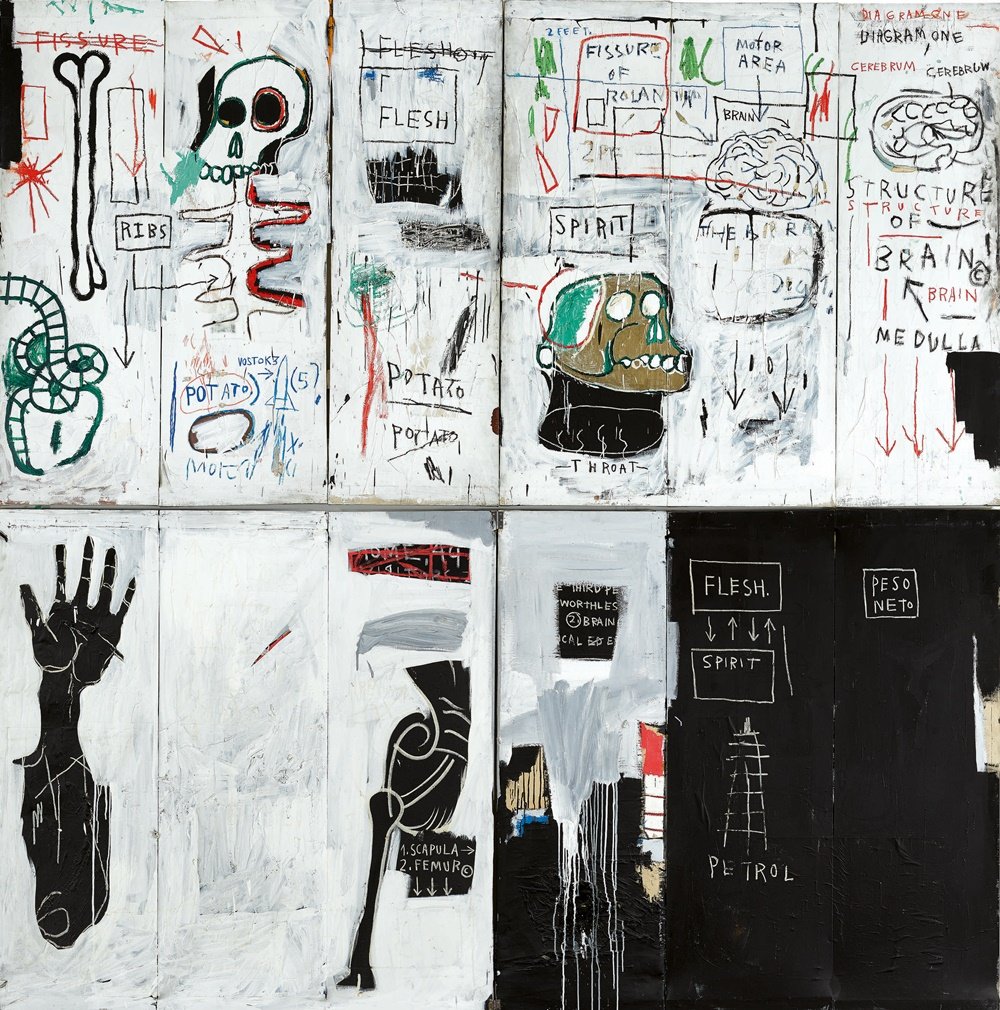

Belinda Neumann Donnelly filed a lawsuit against her father Hubert G. Neumann, yesterday, alleging that Hubert engaged in a “greedy, malevolent, fraudulent, bad-faith and (unfortunately) successful scheme to financially devastate [her mother’s estate, of which she is the agent] and, indirectly, Belinda, by destroying the value of the Estate’s most valuable asset,” Basquiat’s large painting Flesh and Spirit (1983).

It was consigned to Sotheby’s and placed in its contemporary art evening auction on May 16 with an estimate of about $30 million. Bidding opened at $24 million and elicited minimal interest before it was hammered down to a phone buyer for $27 million ($30.7 million with premium).

Neumann Donnelly alleges that the relatively lackluster bidding was a result of her father Hubert’s actions, namely that two weeks prior to the sale he filed a “frivolous complaint” against Sotheby’s, including a motion for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction to halt the sale.

Hubert had argued he had a claim to the work because of a prior agreement he struck with Sotheby’s to sell his art in 2015. The judge, Peter Sherwood, appeared to be incredulous at the claim, judging from transcripts obtained by artnet News. “I am at a loss to understand how he can exercise authority over a piece of work that he and the interest that he represents have no entitlement to,” the judge said.

Documents showed that Belinda’s mother, Dolores O. Neumann, had completely cut her estranged husband out of her will. According to the papers, she wrote: “[I]it is my desire and intent that my husband, Hubert Neumann, be disinherited by me to the fullest extent permitted by law, because he has been physically abusive to me for decades and has threatened my life.” The judge dismissed Hubert’s motion and the sale proceeded as planned.

But Belinda says that the damage was done. The effort “was designed to ensure that potential bidders for the Basquiat would be scared away at the last minute due to perceived uncertainty about the Estate’s right to sell the painting,” according to her complaint.

The papers allege that the value of the Basquiat “was so damaged that it sold for only $30.7 million at the May Auction when it would otherwise have sold for tens of millions of dollars more.” The current record for a Basquiat painting at auction is $110.5 million set at Sotheby’s last May.

Belinda says she plans to produce expert testimony that will demonstrate the price at which the Basquiat “would have otherwise sold absent the misconduct alleged here.” The fact that there were “no f*cking bids” for the painting, in his words, demonstrated the damage his actions caused, according to the complaint.

Among the claims in Belinda’s suit are tortious interference with prospective contractual relations and prima facie tort against Hubert. Though the papers request that punitive damages be determined at trial, she is seeking “no less than $100 million.”

Neither Belinda’s attorney nor Hubert’s attorney responded to a request for comment by publication time. Sotheby’s, which is not a party to the suit, did not respond to a request for comment.