When Chris Burden had a friend shoot him in the arm in 1971, in his legendary performance art piece Shoot, the act took place against the backdrop of the war in Vietnam, on the other side of the Earth. Pointing principally to violence closer to home, but also to brutality as a human phenomenon, the artist Bayeté Ross Smith recently hosted a handful of guests at the Westside Rifle and Pistol Range, on Manhattan’s West 20th Street, to fire .22 rifles. Most of them, including this reporter, were doing so for the first time.

The evening began in a classroom, where a handful of generally artsy people got a quick round of directions from our small and heavily tattooed instructor, John, who covered safety precautions and basics like how to load the gun, where the safety switch is, and how to sight along the barrel. This allowed us to handle the kind of rifles we would be shooting, which were surprisingly heavy. Between the haste with which John covered the instructions and the actual prospect of a loaded, deadly weapon in my hands, I was gripped with anxiety.

There were no bullets in the room, and yet, for the first-timer, it was alarming to see fellow-shooters pointing their guns at one another, albeit accidentally and momentarily. “Careful,” admonished John, playfully, “you are handling a weapon of mass destruction.” Even in the range itself, though, there was little chance of mishap, he explained, informing us that the gun barrels are actually chained to the tables where the shooters stand.

Smith’s project is part of an ongoing effort to foster sober discussion about guns in an era of mass shootings, and when police are killing unarmed African Americans at five times the rate of white people, according to research collaborative Mapping Police Violence. Smith is black, and the conversation he aims to encourage would also deal with questions about who tends to be viewed as a target, and why.

The night of shooting was the second evening of a two-part program. The artist also organized a discussion at New York’s Neue House in September, featuring critical care surgeon Ramon Gist, author Pamela Haag (The Gunning of America: Business and the Making of American Gun Culture), and Darren Leung, ex-cop and owner of Westside firing range, moderated by Brooklyn Museum curator Rujeko Hockley.

The dialogue had its highs and lows, with some provocative discussion about how gun violence activists might better advance their cause and the manipulative ways that firearms are marketed. At other moments, it mirrored the worst of the debate, with Leung proposing that if you’re going to ban guns you might as well restrict knives and baseball bats, which resulted in one belligerent audience member shouting at the owner.

At the firing range, though, all the arguments melted away, and despite our handling weapons, the event was surprisingly jovial.

After inserting five tiny bullets at a time into the cartridge and slotting it into the bottom of the gun, breathing deeply and sighting carefully, I placed 15 bullets precisely at the center of a small paper target from five yards. Even though I’d never so much as handled a gun before, I was a decent shot, it seemed. It was easy to handle a rifle of this caliber; it’s best for hunting squirrels, so it’s hardly a gun that knocks you on your rump with a powerful kickback, and with ear protection on, it seemed to emit only a gentle pop.

Photo Brian Boucher.

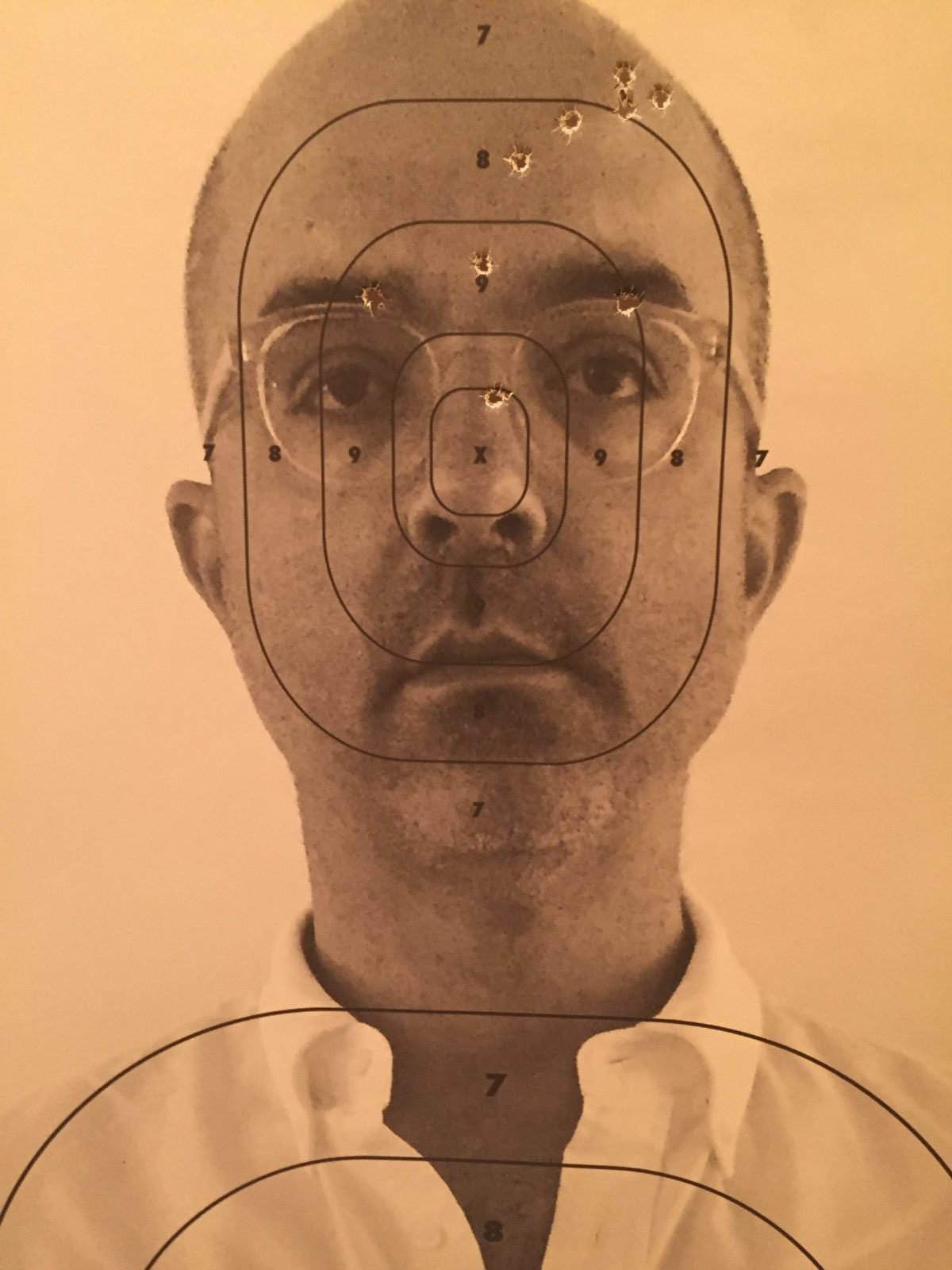

After the small paper targets, we moved on to touchier fare. Smith had asked all the participants to submit photos of themselves, which he had printed onto life-size target sheets, with concentric circles at the chest and the head. Even moving the target much farther away, I managed to shoot myself in the head several times.

Every friend whom I’ve showed photographs of the target of myself has the same reaction: “Creepy.” But as adrenaline kicked in at the firing range, it was all just so entertaining, and the feeling of mastery was intoxicating. Sure, I was shooting myself in the face. But all that mattered was to do it right.

“It’s fun!” Ross said to his novice customers. “People don’t just do this for no reason!”

Some of the participants were more hesitant, with one young woman pointing out that she engaged the gun’s safety after every single, solitary shot. “I’m somehow more hesitant to fire at a woman than at a man,” said another first-time shooter, a graphic designer who seemed genuinely troubled.

All the same, our instructor pointed out that women tend to be better shots, perhaps because they feel they have less to prove, or they don’t go in cocky.

Artist Eric Gottesman and I whooped and laughed when, after we switched up the targets, I took aim first at him and then at fellow-artist Hank Willis Thomas; the two are co-founders of For Freedoms, the political action committee under whose auspices Smith’s event took place. I landed a number of deadly shots despite sending the targets to the maximum distance in the small range. The act of murdering artists in effigy, once I got going, was just an opportunity to play the bad-ass—even for a novice shooter who would love to see all guns disappear from the face of the planet.

“Bayeté is going to sign the target where you shot me in the eye,” Gottesman said to me, “but maybe you should sign it too.”

Affecting a cowboy demeanor, I quipped, “I already did.”

“Or maybe,” Gottesman replied, “that’s just the gun talking.”