Nearly 80 years after her death, Beatrix Potter (1866–1943) remains among the world’s most beloved and popular children’s book authors, having sold 250 million copies of books such as The Tale of Peter Rabbit.

But a new show dedicated to the artist at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum aims to paint a much fuller picture of her life, highlighting Potter’s work in the natural sciences, her stewardship of the English landscape, and her accomplishments as a sheep farmer, as well as her literary success.

“Her legacy can be seen in more than one way,” Annemarie Bilclough, the show’s curator, told Artnet News. “We wanted take a broad view of her achievements beyond her storybooks, because there was such a wide range.”

“Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature” is so titled because “the theme of nature underpins everything she did,” she added.

Beatrix Potter, scientific drawings of a ground beetle (ca. 1887).

Photo ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy of Frederick Warne and Co. Ltd.

The show, which is accompanied by a gorgeously illustrated monograph published by Rizzoli, features 200 artworks, manuscripts, photographs, and other artifacts, including little-known scientific drawings. (For a time, Potter studied to be a mycologist.)

Though Potter lived until London until she was in her 40s, she grew up in a family that had a deep-seated interest in the natural world, fueling her interest in plants, animals, and the landscape. This passion is reflected even in her earliest artworks, a series of sketchbooks done when Potter was eight, nine, and 10 years old. She began formal art lessons at 12.

“She was already drawing scenes from nature, with flowers and landscapes, almost as part of homeschooling,” Bilclough said. “There is a page of caterpillars, and on the other side, she wrote notes about where they lived and what sort of things they ate and what they looked. But she finishes off mid-sentence, as if she forgot to finish her homework.”

Beatrix Potter, sketchbook kept at age nine, dated March–April 1876. Photo ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy Frederick Warne and Co Ltd.

That careful observation of living things is at the heart of “Drawn to Nature,” which is organized in partnership with the National Trust, to which Potter had left the bulk of her manuscripts and watercolors, as well as 4,000 acres of the rural Lake District in northwest England’s Cumbria region.

As a teenager, Potter began vacationing in the area, and fell in love with the picturesque countryside. In 1905, she purchased and moved into the 17th-century farm Hill Top, the first of many properties she bought in the district as part of her efforts to protect the landscape there. (Later in life, Potter actually became a prizewinning breeder of Herdwick sheep.)

Thanks in large part to Potter’s efforts, the entire district has since been designated a UNESCO World Heritage site, and Hill Top is open to the public as a historic site.

Hill Top, the 17th-century farmhouse that was Beatrix Potter’s first property in the Lake District, now a historic site run by the National Trust. Photo ©National Trust Images.

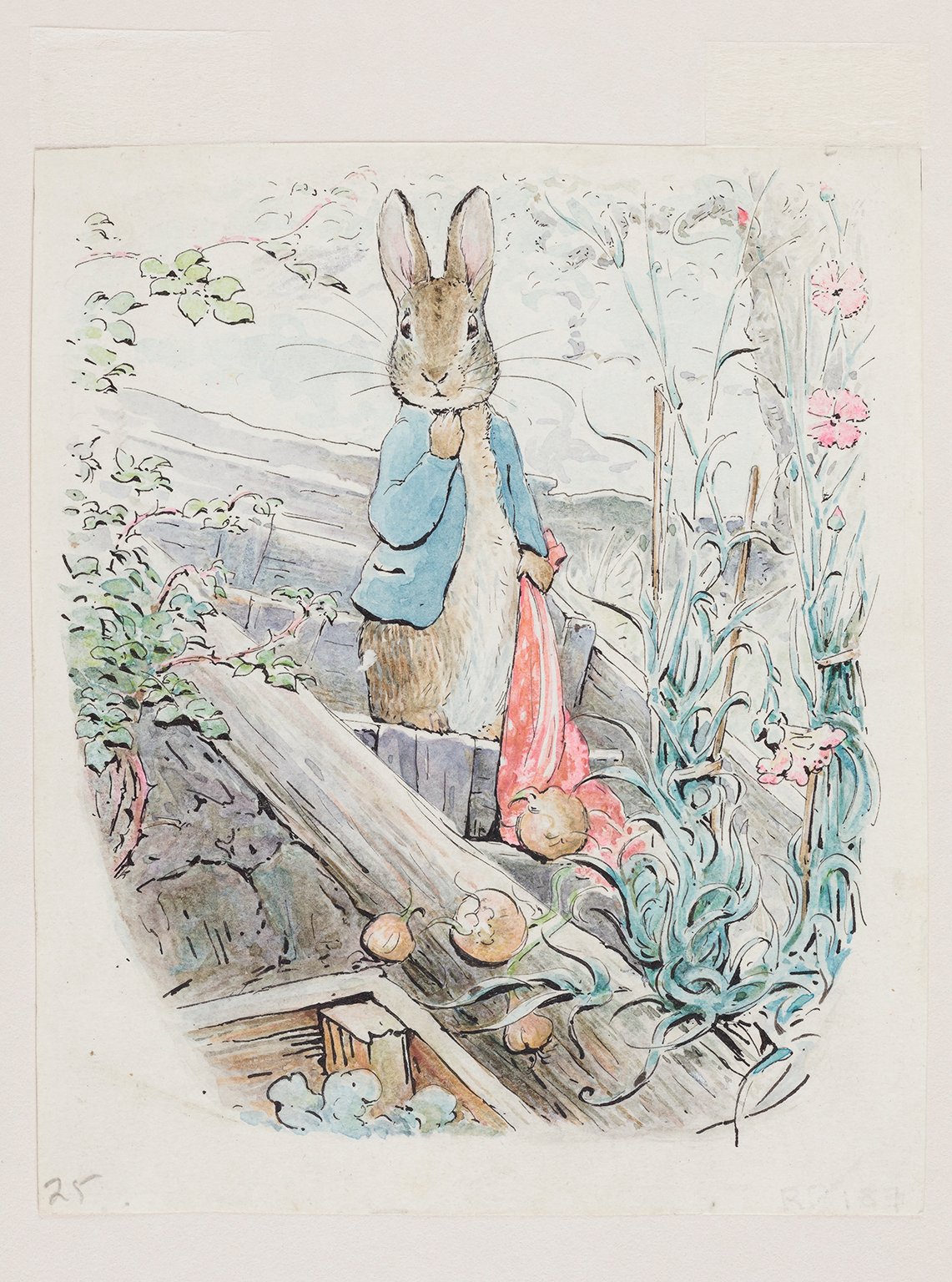

While an astute observer of nature in the wild, Potter often based her drawings on her real-life pets. During her lifetime, she had 92 of them, including rabbits Peter Piper and Benjamin Bouncer, who became Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny, perhaps her best-known characters.

Some books grew out of letters Potter wrote about her pets, often to the children of Annie Moore, who had been her live-in governess and remained a life-long friend.

Scholars have also learned a great deal about Potter’s personality from her journals, which she kept for 15 years, starting from age 14. Her cousin, Stephanie Duke, found the manuscript in Potter’s home in 1952, and turned to Leslie Linder, a scholar and a major collector of the author’s drawings, manuscripts, letters, and other ephemera, to read them, as they were written in code.

Rupert Potter, Beatrix Potter, aged 15, with her dog, Spot (ca. 1880). Photo ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy Frederick Warne and Co Ltd.

It took Linder 13 years to decode it, offering valuable new insight into the author beyond her charming animal stories. It is Linder’s 3,000-piece Potter collection, which he bequeathed to the V&A in 1973, that makes up the bulk of the museum’s Potter holdings and, in turn, a substantial portion of “Drawn to Nature.”

Designed to appeal to Potter fans all ages, the exhibition includes interactive elements and, if you listen carefully, a cheeky soundtrack of mice scrambling in the walls, as if her characters are getting into mischief just out of view.

See more of Potter’s work below.

Beatrix Potter, The Mice at Work: Threading the Needle from The Tailor of Gloucester artwork (1902). Courtesy of Tate, London.

Beatrix Potter, Examples of a Yellow Grisette (Amanita crocea) (1897). Photo ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy Frederick Warne and Co Ltd.

Beatrix Potter, Studies of bees and other insects (ca. 1895). Photo ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy Frederick Warne and Co Ltd.

Beatrix Potter, Cornflowers (ca. 1880). Photo ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy Frederick Warne and Co Ltd.

Beatrix Potter, illustration for Jemima Puddle-Duck (1908). Photo ©National Trust Images.

Beatrix Potter, illustrated letter to Nancy Nicholson (ca. 1917). Photo ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy Frederick Warne and Co Ltd.

Beatrix Potter, Water lilies, probably on Esthwaite Water (ca. 1906). Photo ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy Frederick Warne and Co Ltd.

Beatrix Potter, Four rabbits in a burrow (ca. 1895). Photo ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy Frederick Warne and Co Ltd.

Beatrix Potter, View across Esthwaite Water (1909). Photo ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy Frederick Warne and Co Ltd.

Beatrix Potter, illustrated letter to Noel Moore from Heath Park, Birnam, Scotland (1892). Photo courtesy Princeton University Library.

“Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature” is on view at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 2RL, February 12, 2022–January 8, 2023.