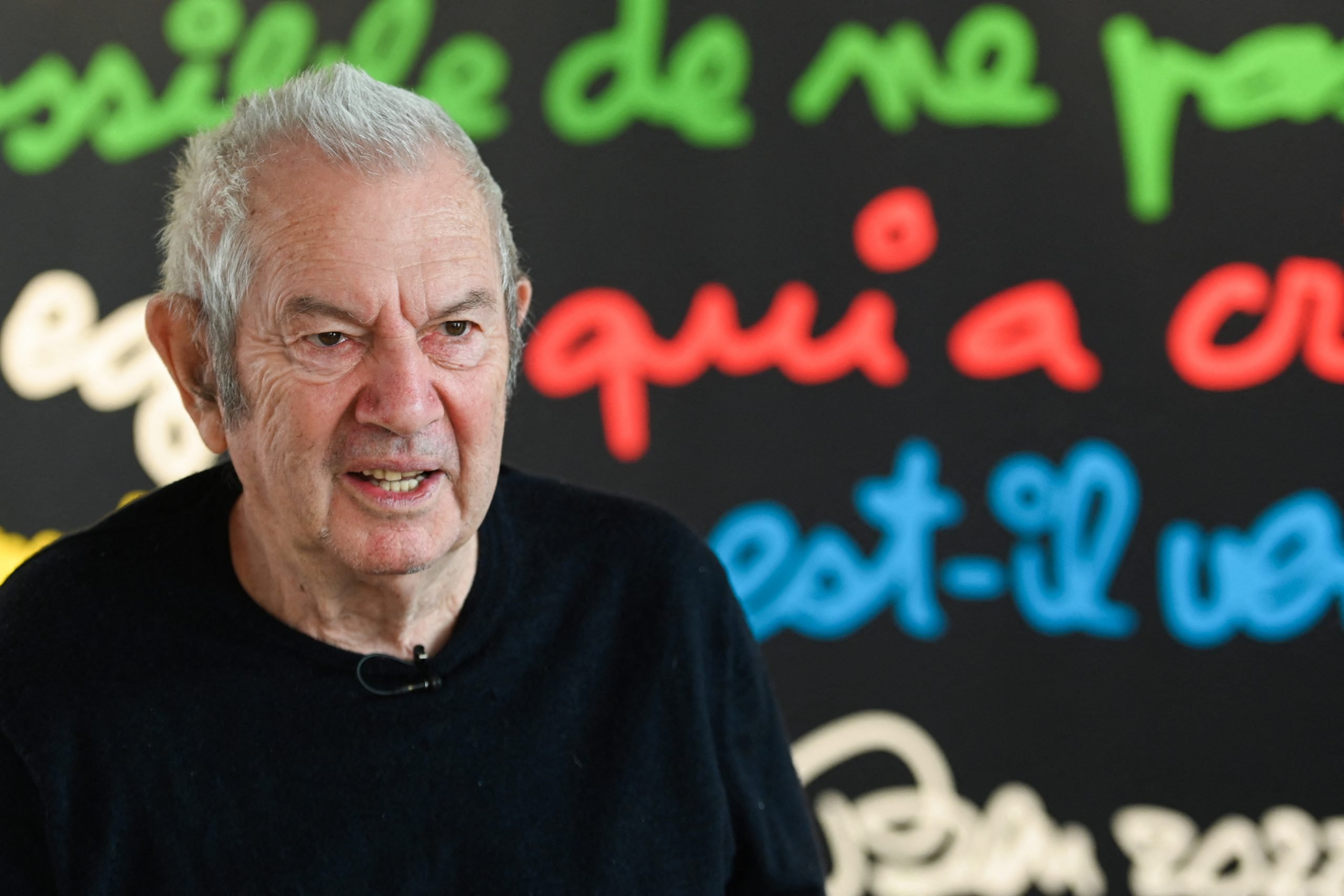

A leading light of the Nice School of artists and the international Fluxus movement, Ben Vautier, more often known simply as “Ben,” is remembered for his highly experimental conceptual practice that inherited the radical spirit of artists such as John Cage, Duchamp, and the Dadaists. Always driven by the pursuit of novelty, Vautier is best known for surprising audiences with performances that made art out of everyday life and for his unique “écritures,” or written paintings.

“My definition of art is: astound, scandalize, provoke, or be yourself, be new, bring, create,” Vautier said in 2010. From early in his career he proudly proclaimed “everything is art.”

At the age of 88, Vautier died by suicide on June 5 at his home in Nice, France, just hours after the death of his wife Annie Baricalla who had suffered a stroke two days earlier. A statement issued by the couple’s children Eva and Francois said he had been “unwilling and unable to live without her” after 60 years of marriage.

Benjamin Vautier was born in Naples on July 18, 1935 to an Irish and Occitan mother and a French-Swiss father; his paternal grandfather was the Swiss painter Marc Louis Benjamin Vautier. His childhood was spent moving between several countries, including Turkey and Egypt, during the war, before settling in Nice in 1949. Vautier would remain there for the rest of his life.

Installation view of retrospective for French artist Benjamin Vautier, also known as Ben, at the Musée Maillol in Paris in 2016. Photo: Bertrand Guay/AFP via Getty Images.

Towards the end of the 1950s, Vautier set up Laboratory 32, a shop selling second-hand records that he kept until 1973. It became a regular meeting place and exhibition space for a community of local artists including Yves Klein, Martial Raysse, Bernar Venet, and Sarkis. At Klein’s encouragement, Vautier began writing all over the walls of the shop, a precursor to his later “écritures” paintings, made by applying white acrylic paint straight from the tube onto a dark ground. The short, simple but irreverent slogans eventually became recognizable throughout France, even adorning pencil cases.

“In my writing, it’s not the aestheticism that matters, otherwise I’d take more care over it,” Vautier once explained. “Generally, I write to be read and understood. It’s the meaning that has to come across.”

In the late 1950s, Vautier also began his “Living Sculptures” series, produced by signing his name on found objects, friends, and even passersby from the street. By 1963, the artist had even signed the entire city of Nice and manufactured certificates of authenticity for the artwork. These actions tested the limits of what could be considered art and what kind of intervention is necessary to assert authorship over an artistic output.

Performance in which French artist Benjamin “Ben” Vautier is suspended 200m above the ground on his bed in Nice, on July 4, 1985. Photo: Christophe Simon/AFP via Getty Images.

Appropriation would become a particular trademark of Vautier’s after he became a member of the amorphous Fluxus movement in 1962 when he met its founder George Maciunas in London. He invited Maciunas to stage a Fluxus festival in Nice the following year.

Further breaking down the limits between art and real life, Vautier used his own body to stage “gestes,” or happenings. In 1962, he spent two weeks in the window of Gallery One in London. In 1964, he performed Hurler, during which he screamed and yelled until he lost his voice. A record of the performance Vomir consisted of vomit stored in a jar and dated June 8, 1962.

By the 1970s, Vautier had received critical acclaim and institutional recognition in Europe. He participated in Documenta 5 in 1972 and, in 1977, helped organize the influential group exhibition “A propos de Nice,” one of the inaugural shows at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. His work is held in several major public collections, including Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Reina Sofia in Madrid, and the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris.