Photo: Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Bjork, (2015). Published by The Museum of Modern Art.

Photo: Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

After the mountain of bad reviews, Björk’s mid-career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art could be called something of a series of bad decisions (see also Ladies and Gentlemen, the Björk Show at MoMA Is Bad, Really Bad, MoMA Curator Klaus Biesenbach Should Be Fired Over Bjork Show Debacle). But what about her book that was published alongside the show? Who knows, maybe Björk’s retrospective comes off better in print than in person.

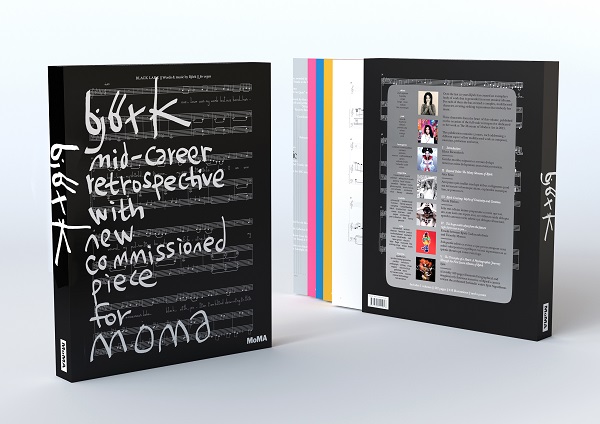

Björk (Museum of Modern Art, March 24) is a beautiful book, let’s get that out of the way; it’s uniquely designed, and was thoughtfully laid out in a hard slipcase that any fan or newcomer to the artist would appreciate. It is a strange book, separated into five booklets with musical score-sheets printed on the covers, each cover getting the score of a different song, each cover a different color, and each one helping us understand the many shades of Björk’s music, art, and life.

With substantial essays by MoMA chief curator at large and MoMA PS1 director Klaus Biesenbach, The New Yorker art critic Alex Ross, professor Nicola Dibben, a poem by the Icelandic poet Sjón, as well as a playful correspondence of published emails between Björk and Rice University professor Timothy Morton, we get a better perspective of the artist’s ideas behind her work, but with few glimpses from the singer herself.

Each of the book’s inserts are designed to look like score sheets.

Photo: David LaGaccia

Biesenbach writes an introduction aimed to readers who may not be familiar to her work, while Ross focuses on Björk’s musical upbringing, talking about how she was raised with a classical education, but disliked the familiar compositions of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven and leaned more towards modern composers, including Arnold Schoenberg, Oliver Messiaen, and John Cage.

In one insightful section, Ross cites New York avant-garde musician Meredith Monk as a key influence to Björk, and writes that in pop music, “the voice conveys a personality, a style, an energy, a brand. In the cases of Monk and Björk, the voice itself becomes the center of gravity of the composition, the fount of the creative idea.”

Dibben gives an academic feminist take on the singer, perceptively arguing that we should look at Björk’s work as complete art projects (costumes, music videos, albums) instead of individual albums. Morton’s correspondence with Björk is probably the closest we get to understanding the nature of the pop innovator’s work, though when the conversation goes towards ideas such as “object-oriented ontology,” it becomes a little convoluted and hard to follow.

Verse from Sjón’s The Triumph of a Heart: A Pschographic Journey Through the First Seven Albums of Björk.

Photo: David LaGaccia

The poet Sjón contributed a book-length poem inspired by Björk’s music. The poem, called The Triumph of a Heart, charts the course of her career set against lush color photographs (some previously unpublished) from all her albums from Debut to Biophilia (photos from the recently-released Vulnicura, are not included).

Surprisingly, Björk’s sole contribution to the book, in her own voice, apart from the missives to Morton, are her sheet music, which is printed on the covers of the booklets.

This book spans the development of an artistic argument about her life philosophy. This may not be something precise, like a single word, but rather is expressed through an image, idea, sound, song or performance, a sum of artistic projects that are inseparable from her life.

If you want to skip the much-maligned show, you can put on your headphones, and let her tell you her life story, and that is the way it probably should be.

For more artnet News coverage on Björk’s mid-career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art see:

Jeffrey Deitch Claims Art World Persecution and Defends Klaus Biesenbach

Art World Reacts to Christian Viveros-Fauné’s Call for Klaus Biesenbach to Resign