What did the ancient Egyptians look like? A new exhibition at National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, the Netherlands, has sparked controversy by including a contemporary artwork that appears to depict the Pharaoh Tutankhamun as Black.

“Kemet: Egypt in Hip-Hop, Jazz, Soul and Funk” pairs Egyptian antiquities from the museum’s collection with work inspired by ancient Egyptian culture by created by musicians of the African diaspora, including Miles Davis, Erykah Badu, Beyoncé, and Rihanna.

The Leiden exhibition acknowledges that while generations of Black musicians have drawn strength and empowerment from ancient Egyptian culture, the racial identity of ancient Egyptians has been a topic of spirited debate for decades.

The show’s title comes from the ancient Egyptians’ name for their homeland, Kemet, which means “black land.” But, the exhibition explains, the color referenced the rich, dark soil of the Nile river valley, rather than the people’s skin tone. The museum also discounts the theory that the noses on many ancient Egyptian statues were broken off in modern times in order to disguise visibly African features.

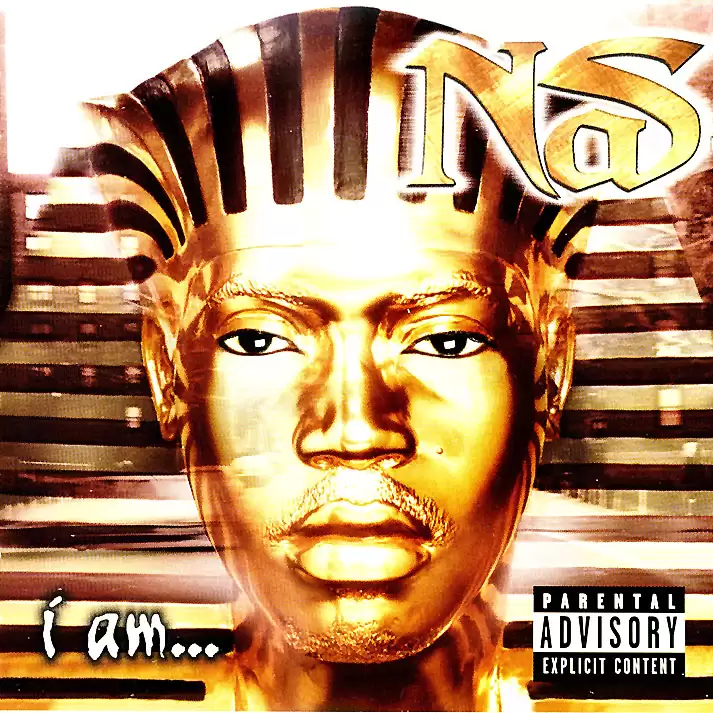

David Cortes, I Am Hip Hop (2019). Photo courtesy of the National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

“This is a very difficult topic and that is the thing with this exhibition: I think you really have to give it a chance,” Daniel Soliman, museum’s Egyptian and Nubian curator, told The Art Newspaper. “There are Egyptians, or Egyptians in the diaspora, who believe that the pharaonic heritage is exclusively their own. The topic of the imagination of ancient Egypt in music, predominantly from the African diaspora, Black artists in different styles, jazz, soul, funk, hip-hop, had long been ignored.”

Nevertheless, the exhibition’s thesis has led to backlash, particularly due to the David Cortes statue, I Am Hip Hop. The 2019 sculpture is based on the 1999 Nas album I Am…, in which the African American rapper was photographed to look like the famed mask of King Tut.

An outraged article titled “Dutch museum claims Tutankhamun was Black” in the Egypt Independent cited a complaint from Egyptian antiquities expert Abd al-Rahim Rihan. Not only does the statue inaccurately depict King Tut’s race, he claimed, the artist has actually created an unauthorized copy of an Egyptian antiquity, which can only be produced by the nation’s Supreme Council of Antiquities under Article 39 of the Protection of Antiquities Law No. 117 of 1983.

The claim has reportedly prompted an official inquiry from Ahmed Bilal al-Burlusy, a member House of Representatives, as to whether Cortes violated Egyptian law. (The piece is a contemporary artwork, not a replica, the museum said in a statement.)

But the exhibition has also fueled long-running arguments about racial identity and cultural appropriation, including on the Facebook group Egyptian History Defenders, which describes itself “defending Egyptian history and heritage against Afrocentric culture vultures.”

There has also been a rash of one-star reviews for the museum on Google, calling it a “woke museum with zero scientific references and heavily under the influence of afrocentrism” who “are forgers who steal the history of Egyptian civilization and attribute it to black African[s].”

“The exhibition does not claim the ancient Egyptians were Black, but explores music by Black artists who refer to ancient Egypt and Nubia in their work: music videos, covers of record albums, photos, and contemporary artworks,” museum director Wim Weijland said. “The exhibition also acknowledges that the music can be perceived as cultural appropriation, and recognizes that large groups of contemporary Egyptians feel that the pharaonic past is exclusively their heritage.”

Adele James, a Black British actress, plays Cleopatra in Queen Cleopatra. Photo courtesy of Netflix.

The question of the race of ancient Egyptians also led to an uproar over the new Jada Pinkett-Smith-produced Netflix documentary-drama series African Queens: Queen Cleopatra and its depiction of the famed ruler by the Black actress Adele James. (An Egyptian lawyer even pushed to block the airing of the series in the African nation, and an Egyptian network has announced plans for its own documentary starring a light-skinned Cleopatra.)

“Netflix is trying to provoke confusion by spreading false and deceptive facts that the origin of the Egyptian civilization is Black,” former Egyptian antiquities minister Zahi Hawass told the al-Masry al-Youm newspaper. “This is completely fake. Cleopatra was Greek, meaning that she was light-skinned, not Black.”

Cleopatra was the last rule of the Ptolemaic dynasty, a Greek-ruled kingdom descended from Macedonians—but her family had been in Egypt for 300 years, and nothing is known about her maternal ancestry.

“While shooting, I became the target of a huge online hate campaign. Egyptians accused me of ‘blackwashing’ and ‘stealing’ their history,” series director Tina Gharavi wrote in Variety, arguing that James was probably more accurate casting than the white Elizabeth Taylor, who famously played the queen in 1963.

“Why shouldn’t Cleopatra be a melanated sister? And why do some people need Cleopatra to be white?” Gharavi asked. “Her proximity to whiteness seems to give her value, and for some Egyptians, it seems to really matter.”

“Kemet: Egypt in Hip-Hop, Jazz, Soul and Funk” is on view at the National Museum of Antiquities, Rapenburg 28, 2311 EW Leiden, Netherlands, April 22, 2023–September 3, 2023.