In 1502, Leonardo da Vinci submitted a proposal for an inventive parabolic-arch bridge that would connect Istanbul with its sister city of Galata. Had it been erected, it would have become the longest such structure in the world ten times over. It wasn’t, though, and so for centuries, engineers have wondered: Would it have actually worked?

Finally, the question has been put to rest.

A team of researchers at MIT, led by architectural professor John Ochsendorf, recreated Leonardo’s bridge in exacting detail. They discovered that, indeed, the Renaissance master’s design would have worked.

Leonardo’s proposal was created in response to an open request from Bayezid II, a sultan of the Ottoman Empire, who sought to connect the two Mediterranean cities in 1502. The inventor’s concept spanned roughly 919 feet, making it significantly larger than most bridges of the era, which were limited to less than 100 feet. What’s more, the design was revolutionary, supporting itself across one large arch. Other bridges of the time required numerous semicircular arches to sustain significant weight.

Needless to say, the sultan chose another bridge proposal. Leonardo’s own design was lost for centuries until being rediscovered in the 1950s.

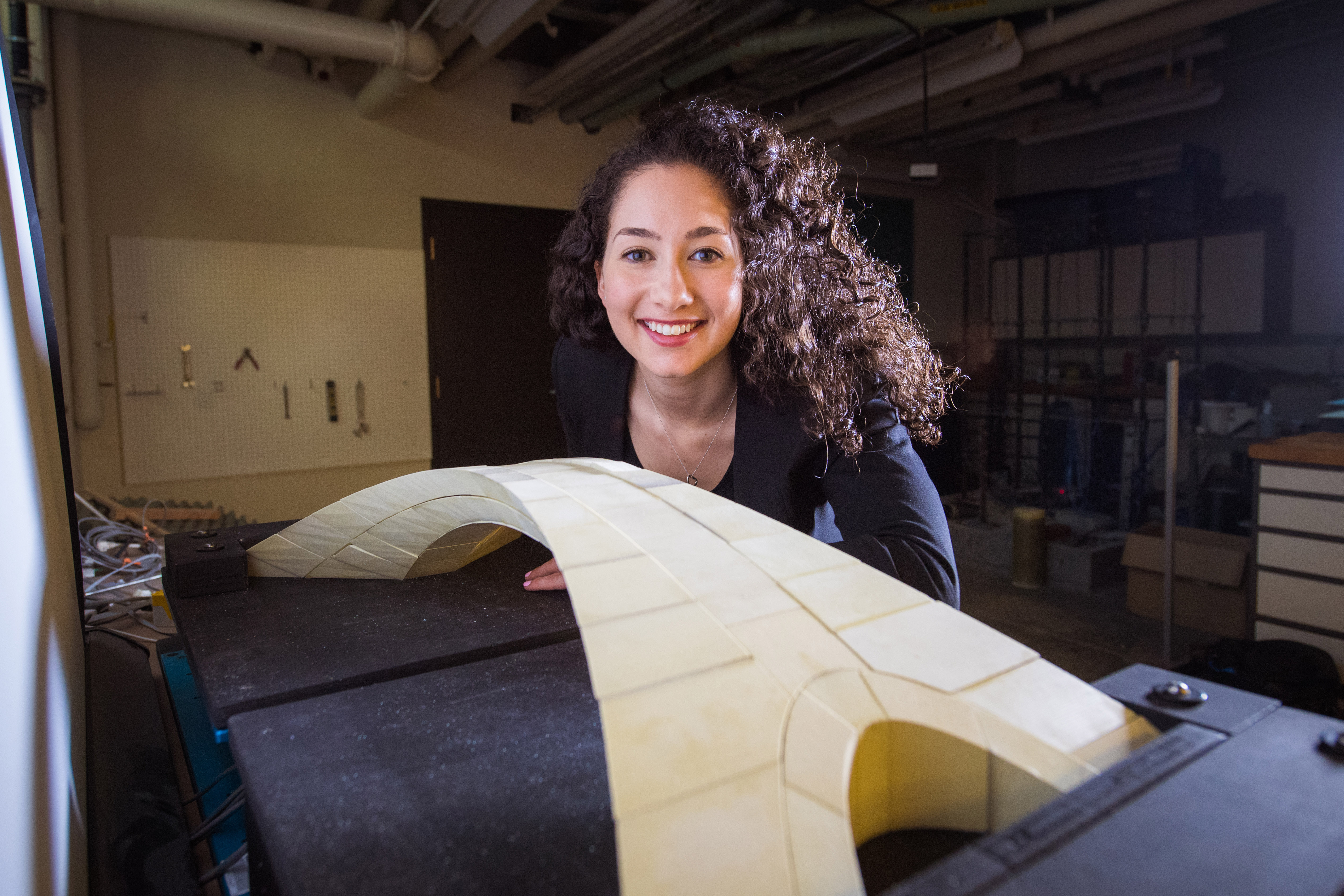

Drawings by former MIT graduate students Karly Bast and Michelle Xie showing how the structure could be divided up into 126 individual blocks, which were 3D printed to build a scale model. Courtesy of MIT. Photo: Karly Bast and Michelle Xie.

Ochsendorf and his team weren’t the first to bring it to life. In the late 1990s, Norwegian artist Vebjørn Sand discovered da Vinci’s bridge studies for himself. Several years later, he realized the design in Ås, Norway, erecting a 1,201-foot walkway for pedestrians to pass over European route E18. However, Sand’s bridge was built with glued laminated timber—a modern material. Leonardo’s proposal called for something more primitive: masonry.

To properly test the bridge, the MIT team studied Leonardo’s plans, researched the materials and methods of construction used for such projects at the time, and factored in the geological specifics of the bridge’s would-be site—the Golden Horn waterway in present Turkey. They then built a 3D-printed scale model to measure the bridge’s load capacity and test against seismic tremors. (Leonardo, evidently, took potential earthquakes into account.) In the end, it was sound.

“It’s the power of geometry,” MIT grad Karly Bast, who worked on the project, told MIT News. “This is a strong concept. It was well thought out.” She added that the success of the Renaissance design illustrates how “you don’t necessarily need fancy technology to come up with the best ideas.”

Ochsendorf and his team presented their findings at a conference for the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures in Barcelona earlier this month.