The first thing to be said about the new exhibition at the British Museum, “Defining Beauty: the body in ancient Greek art” is that it is genuinely spectacular, and deserves the hosannas it has already been greeted with in the press. The second thing is that it is highly political.

It is political in all sorts of ways. The most obvious of these can be found in the fact that it plucks a number of the so-called “Elgin marbles,” which once formed part of the decoration of the Parthenon, from their usual setting in another part of the museum, and presents them as part of a new and sometimes fairly subversive narrative about the relationship of ancient Greek culture to the representation of the human body—nude bodies in particular.

Ilissos. Marble statue of a river god from the Wes

t pediment of the Parthenon

Designed by Phidias, Athens, Greece, 438BC-432BC

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

This offers a statement about the importance of Greek art, and indeed other aspects of Greek culture, to Western European culture viewed as a whole, and a more specific statement about the two-stage return to ideas and values initiated by the ancient Greeks, first during the Renaissance and, second, even more strongly, in response to the European Enlightenment.

Lord Elgin’s rescue of the Parthenon marbles from their forlorn situation in Athens, then part of the declining Ottoman Empire, was without a doubt motivated by that. If he hadn’t shipped them back to London—it must be remembered that he did so with official permission from the then authorities in Greece—it is quite probable that we wouldn’t have them today. There is also no doubt that their new accessibility in London, then as now a world capital, played a considerable role in transforming European ideas about art.

A figure of a naked man, possibly Dionysos

Marble statue from the East pediment

of the Parthenon

Designed by Phidias, Athens, Greece, 438BC-432BC

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Neil MacGregor, the current Director of the British Museum, has mounted a stubborn defense against recent demands that the marbles be returned to Greece, and this exhibition is an eloquent part of it. The recent loan of the figure of the river-god Ilissos to the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg was also part of the same strategy. The sculpture turns up again here, as a prominent item in the show. In fact, the contentious marbles, some though obviously not all of them, are star turns in the show. It’s a fairly obvious provocation.

Those on the opposite side have to remember a number of things. For example, the British Museum, though an “official” institution, is not in fact directly responsible to the British government. It is ruled by a body of independent trustees. No government is legally entitled to order those trustees just to ship the stuff back to where it came from, especially as there is plenty of proof that it was, in the terms of Lord Elgin’s day, legitimately exported.

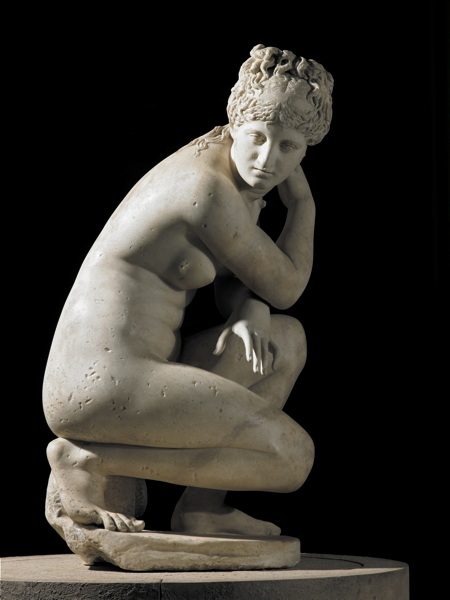

Apoxyomenos

Hellenistic or Roman replica after a bronze original from the second quarter or the end of the 4th century BC

©Tourism Board of Mali Losinj

And certainly no government is going to be anxious to spend parliamentary time on what is likely to be, where the British electorate is concerned, an extremely unpopular cause. In the fairly dim long ago, the then Labour leader, Neil Kinnock, flirted with the Greek actress Melina Mercouri, promising that she would get “her” marbles back. He wouldn’t have had a hope of delivering, had he become Prime Minister—which, as it happens, he didn’t. The even more attractive Amal Alamuddin Clooney, neither a Greek citizen nor a British one, is now busy knocking at the same locked door.

Greece itself currently stands on the edge of two separate catastrophes. One is financial: whether or not it is going to be forced to leave the Eurozone and, further, if its current democratic institutions would survive such a forced exit. One remembers the Greek Junta of 1967-74. The other is the war of Islamic factions in the Middle East, very close to Greece geographically, which has already brought irreparable damage to important archaeological sites such as Nimrud. There’s a real question, quite apart from any niggling legalities, about whether Athens would currently be a good home for these iconic relics of ancient civilization. They’ve already undergone quite a few risky adventures in their long lifetimes, and they show the scars.

Marble statue of a discus-thrower (discobolus) by Myron

Roman copy of a bronze Greek original of the 5th century BC

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The exhibition itself is disruptive in several other ways, quite apart from any political feelings it may provoke. For example, it explores the fact that Greek sculptures were usually highly coloured originally, and, through copies appropriately tinted, it offers some starting examples of what they actually looked like when new. Modern taste, accustomed to “white marble classicism,” finds it difficult to adjust to this. The show is also a lot franker about sexuality and sexual acts than museums were till very recently. Here, for instance, is a black figure cup dating from around 500 B.C., that shows a satyr performing an acrobatic act of mutual arse-licking with a deer. Next to it is a red-figure wine cooler with another satyr balancing a wine cup on the tip of his erect penis. Some parents may think twice about bringing their kiddies.

While the title “Defining Beauty” implies is that the ancient Greeks thought of the nude body—usually the male rather than the female body—as the measure of beauty, the exhibition explicitly contradicts this by showing a very wide range of physical types, both male and female, clothed and unclothed. Socrates, often presented as one of the pinnacles of Greek thought, gets a fairly rough ride. He is portrayed in a small marble statuette and again, all-but-naked, as a little terracotta, in both cases looking far from heroic. And here is a Greek vase, made in his own lifetime, which shows him as a voyeur, watching two youths making love to one another.

Marble statuette of Socrates

A Hellenistic original of the 2nd century BC, or a

Roman copy, Alexandria, Egypt

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The show is largely resourced from the British Museum’s own holdings. There are a few star loans, some wonderful but till now little known, such as the life-size bronze of a young athlete found fairly recently in the sea off Croatia. Others are world famous, such as the Belvedere Torso from the Vatican Museums, which so enchanted Michelangelo. Basically, however, this is an exhibition that is both entertaining and argumentative, populist and intellectually challenging. It makes you think again about things you believed you knew already. It demonstrates to the full how a great museum can make use both of its own collections and of its stored up expertise.